A HOUSE DIVIDED, 1857-1860

The long sectional quarrel convinced North and South that they were so different in culture that they could no longer coexist in the same nation.

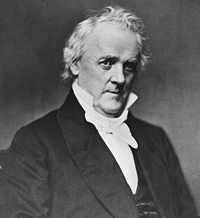

James Buchanan as President

James Buchanan and John C. Breckenridge won the 1856 presidential election over Republicans John C. Frémont and William Dayton and Know-Nothing candidate Millard Fillmore. An experienced politician, Buchanan had served in both the House and Senate in Congress, as Secretary of State under President Polk and as ambassadors to Russia and the United Kingdom. The fact that he was out of the country for the years preceding the election meant that he was not involved in the Kansas-Nebraska act and other divisive issues early in the decade. He is the only president from Pennsylvania, and the only president to remain a lifelong bachelor. In his inaugural address he announced that he would not seek a second term, a promise he kept.

James Buchanan and John C. Breckenridge won the 1856 presidential election over Republicans John C. Frémont and William Dayton and Know-Nothing candidate Millard Fillmore. An experienced politician, Buchanan had served in both the House and Senate in Congress, as Secretary of State under President Polk and as ambassadors to Russia and the United Kingdom. The fact that he was out of the country for the years preceding the election meant that he was not involved in the Kansas-Nebraska act and other divisive issues early in the decade. He is the only president from Pennsylvania, and the only president to remain a lifelong bachelor. In his inaugural address he announced that he would not seek a second term, a promise he kept.

Buchanan has not been a highly regarded by historians, because following the election of 1860, when Abraham Lincoln was elected, he remained in office until after secession had commenced. Although he felt that secession was unconstitutional, he also felt that going to war to stop it was also illegal, so he did nothing. He rejected the idea that he was responsible for the Civil War, feeling that it was Lincoln's problem to resolve. His failure to deal with secession has been called a critical mistake, one of the worst ever made by a president. In defense of Buchanan, his biographer has claimed that he took office in a time when angry passions swept across the nation. That he was able to avoid a crisis during the years1857-1860 is noteworthy, but his failure to act once secession had started remains. It is difficult to see how he could've avoided the Civil War that seemed almost inevitable, having been predicted as far back as 1787 in a speech by George Mason at the Constitutional Convention.

Cultural Sectionalism

Before the actual political division of the nation occurred, American religious and literary leaders split into opposing camps. Southern intellectuals reacted defensively to outside criticism and rallied to the idea of southern nationalism.

Cultural and intellectual cleavages surfaced in the 1840s. Even religion divided North and South. Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians split into northern and southern denominations because of their attitudes toward slave-holding. Southern literature romanticized life on the plantation, and the South attempted to become intellectually and economically independent in preparation for nationhood. At the same time, northern intellectuals condemned slavery in prose and poem. Uncle Tom's Cabin, for example, was an immense success in the North.

The Utah War. The Utah War (1857–1858), sometimes called the Mormon War or Mormon Rebellion was a military conflict between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the United States Army. The conflict lasted for more than a year, though no important military battles occurred, and a peaceful resolution was eventually reached by negotiation. A few brief skirmishes that occur as the Army tried to enter you and were blocked. Some property was damaged, and a number of civilians were killed. Fearing an invasion by the United States government, the Mormon community armed itself and prepared to defend its people. The United States government, on the other hand, hoped to resolve the conflict, the source of which was objections to the culture of the Mormons, which included the right to polygamous marriage, without bloodshed. In the end, full amnesty was granted to the Mormons for the charges of sedition and treason that were issued to the Utah citizens by President Buchanan on the condition that they accept United States federal authority. As a result Brigham Young was replaced as the governor of Utah territory by a non-Mormon appointed by the president.

The Dred Scott Decision: The Supreme Court Takes a Stand

In a controversial case, the Supreme Court ruled that Dred Scott was a slave and that African Americans (whether slave or free) had no rights as citizens. Further, the Court declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, denying that Congress had any power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Rather than resolve disputes over the slavery question, the decision intensified sectional discord.

The Supreme Court had a chance to decide the issue of slavery in the territories when it agreed to consider the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford in 1857. Instead of limiting itself to a narrow determination of the case, the Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise had been unconstitutional because Congress could not restrict the right of a slave-owner to take his slaves into a territory. The ruling outraged the North and strengthened the Republicans.

The Dred Scott decision drove another wedge between the North and South. Scott was a Missouri slave whose master had taken him into Illinois and Wisconsin Territory, then returned to Missouri. Scott sued for his freedom based on his temporary residence on free soil. The real issue was the question of Congress's authority to ban slavery from the territories. In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that blacks were not citizens, so Scott could not sue in federal court. Further, the Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise (which had banned slavery from Wisconsin Territory) was unconstitutional because it violated the slave owners' Fifth Amendment guarantees of due process. The decision also threatened the concept of popular sovereignty, and it undercut the foundation of the Republican party. (400-401)

The Case Posed Three Questions:

- Was Scott free by virtue having lived in free areas? (No)

- Was Scott citizen who could sue in Federal courts? (No)

- Was the Missouri Compromise constitutional (No!)

Scott as a former slave held "not a citizen," therefore not able to sue in federal court; Scott's stay on free soil did not make him a free man; the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional under 5th Amendment (depriving property without due process.)

Each justice handed down a separate decision; (Taney wrote decision for 6-3 majority); Property clearly supersedes liberty. Two justices stated Congress could regulate slavery under Art. IV, sec. 3.

Decision a clear southern victory; northern abolitionists charge slavery conspiracy; further rouses abolitionists. Lowered prestige of court in North and fanned sectional fires.

BUT . . . Republican fall-back position: Since Scott not a citizen, no case is legally before the court! Therefore, all but that part of the decision irrelevant and has no force. Accomplished nothing . . .

Great dilemma of Democracy: What do you do when it comes out wrong?

Dred Scott v. Sanford

The question is simply this: Can a negro whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen, one of which rights is the privilege of suing in a court of the United States....

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument ...

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit....

It cannot be supposed that they (the states that ratified the Constitution] intended to secure to them [African-Americans] rights and privileges and rank in the new political body throughout the Union, which ever-y one of them denied within the limits of its own dominion. More especially, it cannot be believed that the large slave-holding States regarded them as included in the word citizens, or would have consented to a constitution which might compel them to receive them in that character from another State ...

And upon a full and careful consideration of the subject, the court is of the opinion that, upon the facts stated in the plea in abatement, Dred Scott was not a citizen of Missouri within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States, and not entitled as such to sue in its courts....

The Act of Congress upon which the plaintiff relies declares that slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, shall be forever prohibited.. . north of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude, and not included within the limits of Missouri....

But the power of Congress over the person or property of a citizen can never be a mere discretionary power under our Constitution and form of Government. The powers of the Government and the rights and privileges of the citizen are regulated and plainly defined by the Constitution itself ...

The right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. The right to traffic in it, like an ordinary article of merchandise and property, was guaranteed to the citizens of the United States in every state that might desire it, for twenty years. And the Government, in express terms, is pledged to protect it in all future time, if the slave escapes from his owner. This is done in plain words-too plain to be misunderstood. And no word can be found in the Constitution which gives Congress a greater power over slave property, or which entitles property of that kind to less protection than property of any other description....

Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the act of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding or owning property of this kind in the territory of the United States north of the line therein mentioned, is not warranted by the Constitution, and is therefore void; and that neither Dred Scott himself, nor any of his family, were made free by being carried into this territory; even if they had been carried there by the owner with the intention of becoming a permanent resident.

BLEEDING KANSAS and the 1857 LECOMPTON CONSTITUTION

Once again events in Kansas created sectional conflict. The proslavery faction met in a rigged convention at Lecompton to write a constitution and apply for admission as a state. Free-Soilers in Kansas overwhelmingly rejected the Lecompton constitution, but President Buchanan and the Southerners in Congress accepted it and tried to admit Kansas as a state. The House defeated this attempt. The Lecompton constitution was referred back to the people of Kansas, who repudiated it. The Lecompton controversy split the Democrats when Douglas broke with Buchanan over the issue, but Douglas made himself unpopular in the South by doing so. President Buchanan tried to get Congress to accept Kansas's proslavery Lecompton Constitution and admit Kansas as a slave state, but Douglas opposed the fraudulently drawn constitution and the Buchanan-Douglas split shattered the Democratic party. Ultimately, both Congress and the majority of Kansas voters rejected the Lecompton Constitution. When finally submitted to a fair vote by the residents of Kansas in 1858, the Lecompton constitution was overwhelmingly rejected. Kansas remained a territory and finally entered the nation as a free state under the Wyandotte Constitution in 1861 as the “most Republican state in the Union.”

As a result of the controversy over the Lecompton constitution, Kansas had two governments, one legal but fraudulent; one representative but illegal. Gov. Geary, who tried to steer a nonpartisan course, was succeeded by Buchanan appointee, Robert J. Walker.

The struggle in Kansas led to continuing violence as the pro-and antislavery forces clashed with each other. Between the creation of Kansas in the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act and the outbreak of the Civil War, 55 people in the territory were killed. The events in Kansas help stir the national controversy over slavery which eventually led to the Civil War.

Since Stephen Douglas believed in the principle of popular sovereignty, he unwittingly invited conflict as the people in the territory fought to defend their pro or antislavery positions. One armed group was sent to Kansas from New England to fight for and defend the antislavery position. To counter that move, thousands of "border ruffians" crossed the border into Kansas to intimidate the antislavery voters. They enabled the election of a proslavery legislature which was, however, not accepted by the antislavery forces.

Lawrence Kansas became a center of the antislavery movement, and the city was sacked in 1856 by a mob who destroyed printing presses, attacked homes and public buildings. In a counter move, John Brown carried out the Pottawatomie massacre as he and his sons dragged proslavery settlers out of their homes and kill them.

The situation in "bleeding Kansas" resulted in violence in Congress as a senator from South Carolina and Preston Brooks came on to the Senate floor and began beating Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with a cane. Sumner had made a strong speech in opposition to the proslavery people and denounced a southern senator.

The fighting continued sporadically and was also an issue that came up during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858.

LINCOLN AND DOUGLAS: Debating the Morality of Slavery

On June 16, 1858, a Lincoln speech accepts the Republican nomination for Senate from Illinois: "'A house divided against itself cannot stand.' I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other." Lincoln was a logical choice to oppose Douglas in 1858. Their campaign debates were pitched at a high intellectual level, but the differences between the two were exaggerated. Both men opposed the expansion of slavery, and neither was an abolitionist. Both believed slavery was a wasteful labor system, and both believed blacks were inferior to whites.

In the debates preceding the 1858 Illinois Senate race, Abraham Lincoln claimed that there was a southern plot to extend slavery throughout the nation. He promised to take measures that would ensure the eventual extinction of the institution. Above all, Lincoln made the point that he considered slavery a moral problem, while Douglas did not. Lincoln asked Douglas how he could reconcile the idea of popular sovereignty with the Dred Scott decision. Douglas offered the "Freeport doctrine," a suggestion that territories could dissuade slaveholders from moving in by providing no supportive legislation for slavery. Coupled with his stand against the Lecompton constitution, Douglas's Freeport doctrine guaranteed loss of southern support for his presidential bid.

Northerners blamed southerners for the Panic of 1857 since southern Democrats had pushed through Congress a bill to lower tariffs. Lincoln had served a single term in the House during the Mexican War, and he was admired in Illinois for his wit and integrity. He was not an abolitionist and he did not condemn southern slave owners, but he condemned slavery as morally wrong. Although he had no immediate solution to the slavery problem, Lincoln insisted the nation could not much longer remain divided over slavery.

Douglas tried to portray Lincoln as an abolitionist and racial egalitarian, and he painted himself as the champion of democracy. Lincoln countered by pointing to his own opposition to black suffrage and black citizenship, and his endorsement of the Fugitive Slave Law. Lincoln tried to picture Douglas as proslavery and an unconscionable defender of the Dred Scott decision. Douglas slid around this charge when he argued in the Freeport Doctrine that slavery could still be "banned" in a territory by passing local laws that were hostile to slavery. The Doctrine probably won Douglas reelection, but it cost him southern support when he ran for president in 1860. The debates revitalized Lincoln's political career.

- Debates take place August 21-October 15. [Elections to state legislature will determine who gets Senate seat; it's the "only" issue in the campaign.]

- Douglas's "care not" position assailed; Lincoln places Douglas in extreme position; says nation cannot survive half slave, half free.

- Douglas: nation can survive half and half; Lincoln sees ultimate extinction of slavery

- Douglas's "Freeport Doctrine": Territories can prohibit slavery by not passing necessary laws. -- leads to demand for federal slave codes

Elsewhere in 1858, the Republicans fared well. Still, a southern-dominated Congress refused to enact any of the Republicans' pro-business programs. Southerners were growing increasingly uneasy in their relationship with the North; radical "fire-eaters" demanded a federal slave code, the annexation of Cuba, and the reopening of the slave trade.

1858 Southern states move to reopen slave trade overseas; if slavery is O.K., then why not? Would widen ownership by lowering prices, increase political support for slavery in South, where many oppose slavery as destructive.

1859 Abelman v. Booth upholds constitutionality of Fugitive Slave Law.

1859 JOHN BROWN'S HARPER'S FERRY RAID. John Brown, a mentally unbalanced abolitionist who had led a massacre of proslavery settlers in Kansas, organized a raid on the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. He intended to foment a slave uprising and create a black republic. This threat to their lives and property outraged southerners. Brown was captured and executed for treason. Republican leaders denounced Brown's use of violence, but he conducted himself with such dignity during his trial that he was martyred by many in the North. To southerners John Brown was a ruthless symbol of all they feared from abolitionists.

Captured by Col. R.E. Lee, Lt. Jeb Stuart and Marines; Brown makes eloquent final statement: "So let it be done"

The South's Crisis of Fear

In 1857 Hinton Rowan Helper published a book called The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It. It argued that slavery was detrimental to the welfare of white Southerners had heard them economically. The book got wide circulation, but it made Southerners angry as an attack on what was by then known as the "peculiar institution." The book did not appeal directly to abolitionist sentiment, but rather to the self-interest of the white population of the South by urging lower-class whites of the South to unite against planter domination and abolish slavery. . It was an economic rather than a religious or moral argument. Nonetheless, it was reviled in the South.

The other event that intensified the crisis was the sympathy in the north over the execution of John Brown. The objective of John Brown's raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had been to arm an equip a slave army to attack slavery tThroughout the South, and the possibility, however remote, terrified many Southerners. The objective of John Brown's raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had been to equip a slave army. When Brown was executed for treason, the North mourned him as a martyr, which outraged the South.

The white South was disgusted with the attacks on slavery and became convinced that the Republican Party, whose motto in the 1856 election had been Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men, Frémont, would use armed force to abolish slavery. The only solution, it seemed, was to secede if the next president was a Republican.

More on John Brown at Harpers Ferry.

The Election of 1860 and the Secession Crisis

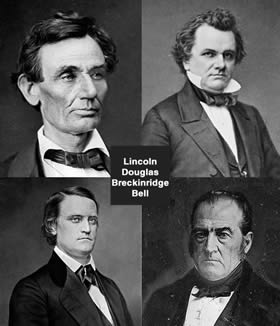

Unable to agree on a platform or candidate in 1860, the Democrats split: a northern wing nominated Stephen Douglas and endorsed popular sovereignty, and a southern wing nominated John C. Breckenridge and demanded federal protection of slavery in the territories. Border state conservatives formed the Constitutional Union party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln on a free-soil position and a broad economic platform. He was successful because he was from Illinois and was not as controversial as other Republican leaders. In order to widen the party's appeal, the Republicans promised high tariffs for industry, free homesteads for small farmers, and government aid for internal improvements.

Democrats could not agree on a candidate. The northern wing nominated Stephen Douglas; the southern Democrats nominated John Breckenridge. The Constitutional Union party ran John Bell, who promised to compromise the differences between North and South.

The 1860 ELECTION:

The election of 1860 took place in a nation divided over the issue of slavery and was the last major event that triggered secession and the virtually inevitable civil war that followed. Radicals on both sides of the slavery issue in the North and South were heedlessly provoking each other. Extremists were more evident in the South, yet southerners sincerely felt they were merely defending themselves against the hostility and growing power of the North. Secession was openly talked about as a way to relieve the sectional tensions.

Democrats. The Democratic Party divided into northern and southern wings over the slavery issue. Southern Democrats refused to nominate Douglas as the party's presidential candidate in 1860 when his supporters refused to guarantee slavery in the territories and accept the moral rightness of slavery. The party split in two. Northern Democrats nominated Douglas on a platform upholding the Freeport Doctrine—the idea that territories could prevent slavery by refusing to pas the laws necessary for its existence. Southern Democrats nominated John Breckenridge and insisted on the enforcement of the Dred Scott decision.

Democrats. The Democratic Party divided into northern and southern wings over the slavery issue. Southern Democrats refused to nominate Douglas as the party's presidential candidate in 1860 when his supporters refused to guarantee slavery in the territories and accept the moral rightness of slavery. The party split in two. Northern Democrats nominated Douglas on a platform upholding the Freeport Doctrine—the idea that territories could prevent slavery by refusing to pas the laws necessary for its existence. Southern Democrats nominated John Breckenridge and insisted on the enforcement of the Dred Scott decision.

The Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. The Republican platform opposed slavery in the territories and advocated a high tariff, a homestead law, and building the transcontinental railroad. With the moderate Lincoln, Republicans hoped to capture the key states just north of the Ohio River. Remnants of the Know Nothing and Whig parties formed a Constitutional Union party, nominated John Bell, and endorsed the Constitution. Lincoln won the election with only about 40 percent of the popular vote, but he swept the North and West and amassed a comfortable Electoral College majority.

The Union Party nominated John Bell In a desperate attempt to save the nation, but had little chance of attracting any electoral votes.

Realizing that he could not win, Stephen Douglas campaigned in the South, urging the states not to secede. The Republican Party platform stated that “the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom,” and opposed any extension of slavery. Republican Abraham Lincoln won the election with less than 40% of the popular vote. The vast majority of Lincoln's votes came in the North; in some southern districts he did not receive a single vote.

As predicted, Lincoln's election and the Republican platform create a crisis and led immediately to moves for secession.

Secession: The Last resort. When all else had failed in terms of ways of protecting the institution of slavery and allowing its extension into new territory, the Southern states turned to secession as a last resort. Secession was first discussed in the northern states in the period leading up to the War of 1812 when New Eng;anders were beginning to resent what they were calling the “Virginia dynasty.” Following the Mexican-American War Southern representatives met in Nashville to discuss the issue. Secession was vigorously debated during passage of the Compromise of 1850. Henry Clay of Kentucky, a slave owner, had argued “that in my opinion there is no right on the part of any one or more of the States to secede from the Union.” Daniel Webster thought secession a “moral impossibility.” but going back as far as the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions of 1798 the issue of states rights had hovered over the union as a threat. Before and during the war of 1812, there was serious talk of secession in New England. when South Carolina challenged federal law with its nullification ordinance of 1832, the relationship between federal and state power was once again tested. The last step remaining, however, for those who wished to assert the right of states to full autonomy if they so chose was not tested until the Civil War. In a sense the case of Texas v White was moot, in that the blood of 600,000 Americans had been spilled to resolve the issue by force.

A careful reading of the South Carolina Ordinance of Secession passed in December 1860 reveals that even that state acknowledged the existence of a contract between the state of South Carolina and United States, or as they put it, with the other states in the union. In that document South Carolina argued that because many Northern states had passed laws in effect nullifying or overriding the new Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, thus exercising in their states' rights, they had thus broken the contract that bound the union together. In so doing, South Carolina argued, “The constitutional compact has been deliberately broken and disregarded by the non-slaveholding states; and the consequence follows that South Carolina is released from her obligation.”

Looking at the issue from it extralegal standpoint, it makes little sense to claim that a document creating a nation would somehow within it sow the seeds of its own destruction. But the issue of slavery had been debated back as far as the time of the writing of the Constitution and even before. The issue of slavery was not resolved when the Constitution was written, primarily for two reasons. First, a Constitution that provided for even the gradual abolition of slavery would never have been ratified by the Southern states, and six of the 13 original states were slaveholding states. In fact slaves existed in most northern states at the time of the writing of the Constitution, although slavery was clearly on its way out through much of the North. The second reason why the Constitution did not address slavery was that in 1787 there was reason to believe that slavery was losing its grip everywhere. It was the emergence of the cotton economy beginning in the 1790s and early 1800s that transformed slavery into an absolute economic necessity for the South.

The issue of slavery, as one historian has said, was old when Moses was young. In America it had existed for well over 200 years, and many Americans had a nagging feeling that the presence of this "peculiar institution" was somehow going to disturb the peace and tranquility of the nation. The issue had arisen during the American Revolution and had surfaced again at the Constitutional convention. At the time of the Missouri Compromise in 1820, Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter, "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever." As agitation over slavery continued through the time of the late war, it seemed that God's patience was indeed wearing thin.

In 1868 the United States Supreme Court heard the case of Texas v. White. The case arose out of the issue of United States bonds that had been issued to the government of Texas in 1851. During the civil war the secession government of Texas saw again the bond and it was out of that request that the case originally came about. the issue of the bonds is secondary; the real issue was whether the Confederate government of Texas was illegal government under the United States Constitution. The court ruled that, “The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States...,” and thus it formally declared that secession was incompatible with the Constitution designed to create “a more perfect union.” The articles of Confederation had explicitly stated that the union of United States formed thereunder was to be permanent, and the court concluded that if the union under the Constitution was to be more perfect, it was certainly meant to be permanent. Therefore secession was unconstitutional.

Could secession have been avoided? It is difficult to see how, once slavery had been protected within the Constitution, that there was any way to abolish it except by agreement of the state's where it existed. If the principles of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had been brought into the Constitution, thus limiting the further spread of slavery, it probably would have died out without a civil war. If the state of Virginia had abolished slavery when they rewrote their constitution in 1830, that might have made a difference. But Virginia was dominated by the Tidewater, eastern section of the state, and the 50 counties that have became West Virginia, where there were few slaves, were underrepresented.

Abraham Lincoln, an able historian as well as skilled lawyer, stated his position on secession in his first inaugural address, as follows: “I hold that in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination.” The entire address is, in fact, a lengthy dissertation on the issue.

In the end, the fact is that by 1860 the divisions in the country over slavery had become so heated that it is unlikely that anything could have prevented war. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster had both seen that in 1850, and others had made the same assertions. Once the session began to unfold, however, there were those who doubted that it would lead to war. That could not have been much more than wishful thinking. As Lincoln saw it, he had no choice but to execute the laws under the Constitution which he had sworn to defend. The only question was, who would fire the first shot?

Following his debates with Stephen Douglas in the Illinois senate race in 1858, Abraham Lincoln became the spokesperson for all those opposed to the further extension of slavery into the territories. His famous debates with Douglas were published widely in newspapers and although he had never traveled widely outside Illinois, he had suddenly become a national figure. Although an extremely humble and modest man, Lincoln was nevertheless a clever and ambitious politician.

The Republican Party, meeting in Chicago, nominated Abraham Lincoln on a free-soil position and a broad economic platform. The nominating process centered around several strong candidates. New York Governor William Seward, the pre-convention favorite, was too radical—too close to being an out-and-out abolitionist. Salmon P. Chase of Ohio was also considered too radical. Edward Bates of Missouri was too weak on the slavery issue. Lincoln men worked to get him in the position of being “everybody’s second choice.” He won the nomination on the third ballot. They nominated Lincoln because he was from Illinois and because he was not as controversial as other Republican leaders. Lincoln’s rivals, Seward, Chase, Bates and Senator Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, all eventually became members of Lincoln’s cabinet. (See the 1860 Republican Platform, Appendix.)

(For a fascinating account of the Republican Convention and the workings of Lincoln’s administration, see Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin, New York, 2006.)

Although Lincoln won only 40 percent of the popular vote, he swept the North for a majority of the electoral votes and election as president. He received no southern votes in the electoral college, and in some southern counties he did not receive a single vote. As predicted, Lincoln's election created a crisis, despite the courageous efforts of Stephen Douglas, who, realizing he could not win, campaigned in the South arguing against secession—to no avail, as it turned out.

Immediately upon learning the election results, the state of South Carolina, which had been in the forefront of the agitation on the slavery question, called a special convention to consider the issue of secession. The secessionists staked their case on fears that the institution of slavery would be attacked by the “Black Republicans,” and that their wives and daughters would not be safe if the slaves were freed. The convention unanimously adopted an ordinance which, having reviewed the issues confronting the slave states, and claiming that the free states had not upheld their contractual obligations under the Constitution, declared:

We, therefore, the people of South Carolina, by our delegates in convention assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, have solemnly declared that the Union heretofore existing between this state and the other states of North America is dissolved; and that the state of South Carolina has resumed her position among the nations of the world.

Thus on December 20, 1860, South Carolina left the Union. By February, 1861, the six other states around the edge of the South—Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas—had also seceded. President Buchanan, feeling with some justification that he had not created the situation, saw no immediate way to resolve it. Congress attempted to find possibilities for compromise, including the introduction of the 13th amendment to the Constitution which would have guaranteed permanent existence of slavery in states where it already existed. Given the decades of angry confrontation between the North and South, it was very unlikely that a compromise had any real possibility of being accepted by either side.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president. In his inaugural address, he reiterated his position that, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” He asserted his belief that the Constitution was perpetual and that secession was therefore illegal. Declaring that as far as he was concerned the Union would continue and all federal services would continue to operate, he claimed that he offered no threat to the southern, seceded states. His address was, however, seen by many in the South as a direct threat to their sovereignty, as they saw it.

In his closing words, Lincoln appealed to his countrymen to be patient:

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.” I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Sadly, it was too late for reconciliation.

Decision to Secede. Ample evidence exists of the centrality of the slavery issue in other documents, such as the speeches and communications made by the secession commissioners from the first seven seceded states to the other slave states which had not yet followed them. One such letter addressed from an Alabama legislator to the North Carolina legislature claims that the federal government “proposes to impair the value of slave property in the States by unfriendly legislation [and] to prevent the further spread of slavery by surrounding us with free States.” In a speech to the Virginia Secession Convention a Georgia representative expressed his fear that soon “the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything.” (See Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001.)

Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States, said this to the Virginia Convention on April 23, 1861:

As a race, the African is inferior to the white man. Subordination to the white man is his normal condition. He is not his equal by nature, and cannot be made so by human laws or human institutions. Our system, therefore, so far as regards this inferior race, rests upon this great immutable law of nature. It is founded not upon wrong or injustice, but upon the eternal fitness of things. Hence, its harmonious working for the benefit and advantage of both. … The great truth, I repeat, upon which our system rests, is the inferiority of the African. The enemies of our institutions ignore this truth. They set out with the assumption that the races are equal; that the negro is equal to the white man.

If slavery was not the root cause of the Civil War, a study of documents from the period before 1861 provides little evidence of any other cause. As to claims that secession may have been caused by slavery but the Civil War was not, it is difficult to separate the two.

That is not to say that all the brave men who went off to fight for the Confederacy were fighting for slavery. Nor did Union soldiers enlist in order to end slavery, though some on both sides were no doubt motivated by the slavery issue. As we shall see, however, as the war progressed, the slavery issue rose to the fore over and over. Indeed, after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, some Northerners were heartened that the Union was to be preserved without slavery. Others were angered and refused to fight “to free the slaves.” Ironically, by the end of the war, the Southern position had less to do with slavery than with gaining independence. In March, 1865, Confederate Secretary of State Judah Benjamin proclaimed that slaves who would fight for the South would be freed. By then, however, the war was all but over.

Points to review as we enter the Civil War:

- The issue of slavery was emotionally charged and thus difficult to resolve.

- Many people in the North did not understand what slavery was really like.

- Many in the South saw slavery as a positive good.

- Slavery was the main issue that had to be resolved during debate over the Compromise of 1850.

- The controversy over slavery was political, economic, moral and religious.

- Once it was recognized and protected by the Constitution, slavery would be hard to eliminate.