The Women's Rights Movement

Copyright © 2005-6, Henry J. Sage

The Women’s Movement: Seneca Falls.

In 1848 a group of women gathered at Seneca Falls, New York, to take a stand for the rights of American women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton had attended a world anti-slavery conference in London in 1840 and was frustrated because women were not allowed to speak. Lucretia Mott, a Quaker, was very active in the abolitionist movement but was also concerned about women's rights—or lack of them. At a social gathering of the two women and others near Stanton’s home in Seneca Falls a group of Quaker women—Stanton being the only one who was not a Quaker—began discussing women's rights. They decided to hold a conference about a week later.

In 1848 a group of women gathered at Seneca Falls, New York, to take a stand for the rights of American women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton had attended a world anti-slavery conference in London in 1840 and was frustrated because women were not allowed to speak. Lucretia Mott, a Quaker, was very active in the abolitionist movement but was also concerned about women's rights—or lack of them. At a social gathering of the two women and others near Stanton’s home in Seneca Falls a group of Quaker women—Stanton being the only one who was not a Quaker—began discussing women's rights. They decided to hold a conference about a week later.

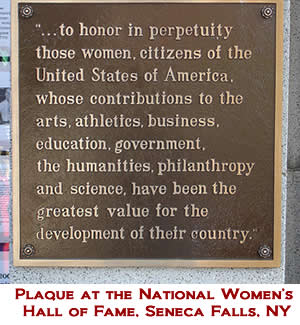

They placed a notice in a local newspaper, and a gathering of about 300 attended the meeting in a Methodist church. Stanton had drawn up a declaration of sentiments and a list of resolutions to be considered. Although this meeting and other ones were met with ridicule from the male population, the declaration and resolutions were published in a New York newspaper and thus received considerable publicity. Although many of their goals would be decades in coming, the conference was a milestone in the progress of rights for women. The National Women's Hall of Fame is now located in Seneca Falls, New York.

Stanton based her declaration on Jefferson's great Declaration of Independence. She began:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. (See full text.)

The meeting in Seneca Falls led to creation of the National Woman’s Rights Convention, a series of annual meetings organized to promote women’s rights. In May 1850 some of the women who had been at Seneca Falls and who were attending the first World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, decided to take advantage of the gathering. They invited those interested in discussing women’s rights to stay on in Worcester. Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis, Lucy Stone and others spent the summer planning the convention. Approximately 1,000 people attended, and Paulina Davis was elected president. In her keynote address she said:

The reformation which we purpose, in its utmost scope, is radical and universal. It is not the mere perfecting of a progress already in motion, a detail of some established plan, but it is an epochal movement—the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions. Moreover, it is a movement without example among the enterprises of associated reformations, for it has no purpose of arming the oppressed against the oppressor, or of separating the parties, or of setting up independence, or of severing the relations of either. …

…

Men are not in fact, and to all intents, equal among themselves, but their theoretical equality for all the purposes of justice is more easily seen and allowed than what we are here to claim for women. … [T]he maxims upon which men distribute justice to each other have been battle-cries for ages, while the doctrine of woman's true relations in life is a new science, the revelation of an advanced age,—perhaps, indeed, the very last grand movement of humanity towards its highest destiny, —too new to be yet fully understood, too grand to grow out of the broad and coarse generalities which the infancy and barbarism of society could comprehend.

The conference was favorably reviewed in the New York and Boston press. Subsequent meetings were held in Syracuse, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere. In the 1860s, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony began the work for women’s suffrage. It was finally achieved in 1919, although several territories and states had already given women the right to vote—as early as 1869 in Wyoming. The women’s movement has continued into the 21st century. Although women have made enormous strides, many would argue that fully quality has not yet been achieved.

Milestones:

- Mary Wollstonecraft: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792

- The Seneca Falls Declaration of 1848

Pre-American. The history of the Western world is filled with stories of intelligent, powerful women who rose above their limited status to achieve greatness in one sphere or another. The Empress Theodora, wife of Byzantine emperor Justinian was one. Cleopatra was another, as were many of the wives and mothers of the Roman emperors. Other famous women leaders before the time of the American Revolution included:

- Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England and of France, 1122-1202. One of the most influential figures of the 12th century, she was the wife of two kings and mother of two kings and ruled England herself while her son Richard the Lionhearted was off on a crusade.

- Joan of Arc, Leader of the French Army, 1412-1431. Joan led the French Army of Charles VII against the English and raised the siege of Orleans. She was eventually captured, put on trial and was burned at the stake. She was canonized a Saint in 1920.

- Isabella I of Castile, Queen of Spain, 1451-1504. She and her husband Ferdinand ruled Aragon and Castile, which eventually became Spain. She was a warrior and reformer.

- Catherine de Medici, Queen of France, 1519-1589. Catherine was married to Henri, Duke of Orleans, who became the King of France in 1547. When he died she assumed political power, acting as regent for her sons. She was heavily involved in court politics and worked to increase royal power.

- Mary Queen of Scots, 1542-1587. Mary became Queen of Scotland at the age of six days. When she was five she was sent to be raised in the French court, and eventually married King Francis II. Mary returned to Scotland, where a political crisis led her to flee to England, where she was seen as a threat to her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, who eventually had her executed.

- Elizabeth I, Queen of England, 1533-1603. Elizabeth the Great, or “Good Queen Bess,” was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Following the death of her half-sister Mary, she soon became one of England’s most powerful and popular monarchs. Following defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, Elizabeth, the “Virgin Queen,” lent her name to the first permanent English colony in North America.

- Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. 1729-1796. Catherine was a German, married to Grand Duke Peter, who was to become emperor. He was unpopular, however, and Catherine arranged his death and took power herself. Considered an “enlightened despot,” she instituted reforms in law, education, and government.

While it is true that for most of western history women were considered to be inferior to men mentally, spiritually, physically, and socially, it is nevertheless self-evident that women were neither stupid nor foolish. Behind the scenes and within families they often wielded far more influence than they were officially or formally granted.

In 1792 Mary Wollstonecraft published “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman,” the first modern feminist tract. Even as she wrote, American women, stirred by the fervor of the American Revolution, were gaining consciousness of their proper place in the new democratic society being created. Women like Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Eliza Hamilton, Dolley Madison, and many others contributed significantly to the growth of American republicanism from their positions as wives and advisors to the founding fathers. While some feminists have sometimes denigrated the roles of wife and mother, the concept of “republican motherhood” was alive and well in American women, who often believed that “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.”

Oddly, while women that had been highly valued in colonial times because of the general shortage of labor and the need for all members of the family and society to be productive, following the revolution women's rights tended to move in reverse for a time. Even as wives were relegated to fully second-class status, however, many fathers, recognizing the importance of educated women in keeping democracy progressive, saw to the training and education of their daughters in a very positive way.

Led by women who had benefited from a solid upbringing, and with the sometimes grudging support of their husbands, women soon began to seek more roles for themselves in American society. Touched by the plight of African slaves, they became very active in the abolitionist movement. They also got involved in various reform movements, including treatment of the mentally ill, movement for temperance in alcohol use, but even in those noble pursuits, they found themselves frequently shuttled to the back rows, thus being denied the opportunity to participate fully in many events.

Thus, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and some of her colleagues, women brought together an assemblage in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, and published their famous Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. The Seneca Falls Declaration of 1848 was not the beginning of the women's movement, nor was it by any means the end. It was a clear milestone, however, in the advancement of American women, who later took the Civil War as an opportunity to move out of their traditional spheres. Following that great conflict they continued to work for even more rights, especially suffrage—the right to vote.

Curiously, their plea for full political rights was first heard in an underpopulated, remote western state: Wyoming. In 1869 the state of Wyoming became, in its own words, “the first jurisdiction in the world to grant equal rights to women.” A number of other Western states followed, but it was 50 years before the 19th amendment finally granted women the right to vote nationally; they participated in their first presidential election in 1920