The Civil War Part 2: Gettysburg to Appomattox

Gettysburg: The Second Turning Point, July 1-3, 1863

The Battle: Day 1, July 1

The Battle of Gettysburg occurred more or less by accident. Neither General Lee nor General Meade, who replaced Hooker in command only a few days before the battle, had planned to fight there. General Ewell, now commanding Jackson’s corps, was headed toward Harrisburg. But some of Lee’s troops commanded by A.P. Hill, always on the lookout for provisions, sent a detachment toward Gettysburg. The town was small, but a dozen roads crisscrossed the landscape, and a railroad was under construction.

Ever since Stuart had departed days earlier, Lee had been without his eyes and ears. Thus Lee did not know exactly where the Federals were. He was unaware that the Union 1st Corps under General John Reynolds was approaching Gettysburg from the southeast direction. The Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia were about to clash in the largest battle ever fought in America. When a scout reported that the Union army had crossed the Potomac, Lee began concentrating his army.

Union cavalry in the capable hands of General Buford was reconnoitering Southern Pennsylvania in advance of the Union Army, which was making its way along the Baltimore Turnpike. On the morning of July 1 Buford's troopers were passing through Gettysburg when the general discovered a division of A. P. Hill’s Corps under the command of Henry Heth just west of the town. Buford sent word back to Reynolds of the enemy approach. Buford judged that the high ground around Gettysburg would be good ground on which to fight and decided to take Heth’s men under attack. Heavily outnumbered, Buford sent further word back to Reynolds, urging him to hurry his corps forward.

Reynolds’s 1st Corps and Hill’s Corps soon clashed on the northwestern outskirts of the village, while General Ewell was called from his advance towards Harrisburg to join the action at Gettysburg. The arrival of Union General Oliver O. Howard’s 11th Corps helped to shift the balance toward the Union, which was outnumbered for much of the day. (The Confederate Corps were larger than those of the Union.) The Union men were driven back through the town of Gettysburg and onto some high ground to the south and east of the town—Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Ridge. That's where the fighting ended the first day. For the time being Lee appeared to have the upper hand. The battle, however, was far from over.

|

Day 2: July 2 Neither General Lee nor General Meade had been present on the ground when the fighting began on the first day at Gettysburg. Lee was drawn to the action by the sounds of fire from Heth’s division and quickly sent officers forward to determine what was going on. Not expecting a full-blown battle while his army was still divided, Lee nevertheless realized the he was too heavily engaged to break off the action, so he urged his remaining divisions forward. By the end of the day he had established himself on Seminary Ridge, a strip of high ground backed by woods on the southwest side of the town of Gettysburg. General Ewell’s Corps, which had joined the action during the first day, was deployed around to the northeast side of Gettysburg facing Culp's Hill. Part of Hill’s II Corps was arrayed along the northernmost segment of Seminary Ridge, and that component of Longstreet's Corps which was already on the battlefield was south of Hill's men. (See Map, left.) General Meade had arrived late in the evening of the first day of fighting and called his officers together in to assess the situation. With parts of his army and some of his supplies still advancing along the Baltimore Pike from the southeast direction, Meade understood that defending his position on Culp’s Hill was crucial. By the next morning, General Slocum’s XII Corps was entrenched on Culp's Hill, with Howard's XI Corps on his left flank and Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps extending to the South along Cemetery Ridge. On Hancock’s left Flank was Daniel Sickles’ III Corps. Lee's lines were stretched along Seminary Ridge about a mile to the west of the Union army. Having been successful with a double envelopment at Chancellorsville, Lee decided to again attack the flanks of the Union Army. But Gettysburg was a different place, and leadership in the Union army had been shaken up in the month since that last battle. Most important, Stonewall Jackson was no longer Lee’s top lieutenant. Lee's instructions to General Ewell were to take Culp’s Hill “if practicable,” the sort of command Jackson would have taken as leaving no room for doubt. Ewell threatened the Culp's Hill position, coming within yards of the Union supply train, but he never broke through. Culp's Hill remained firmly in Union hands throughout the second day. The southern flank of the Union position was to become Longstreet's responsibility. |

Longstreet and Lee

On the south end of the battlefield, General Longstreet was directed to advance on the left flank of the Union line on the southern portion of Cemetery Ridge. A crucial piece of ground, Little Round Top, was unoccupied for most of the day, but Longstreet felt that a move around to the rear of the Union line behind Round Top and Little Round Top would be more effective. The details of the fighting on the second day are readily available from multiple sources. Most critical for the outcome of the battle, a Union officer had discovered that the high ground on Little Round Top was uncovered, and quickly dispatched Union troops to protect it. The famous 20th Maine regiment under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain held off attacks from three Alabama regiments. At the end of the day the Union line stretched from Culp's hill to Little Round Top, with its seven corps arrayed in the famous fishhook formation. The three Corps of Lee’s army were arrayed from the northwest facing Culp’s Hill to the south along Seminary Ridge facing the Union line across a mile or so of open ground. Suffice it to say that neither Ewell nor Longstreet accomplished what General Lee had in mind.

After the war, there was much criticism of Longstreet's behavior on the second day of Gettysburg. Following the war the reputation of Robert E. Lee grew to almost godlike proportions. Unwilling to believe that Lee could have been defeated if all of his generals had obeyed his counsel, Southern writers made Longstreet the scapegoat for the defeat at Gettysburg, second in importance only to the fact that Stonewall Jackson had been killed at Chancellorsville. As Lee's reputation grew after his death, Southern writers "rode Longstreet unmercifully for decades"; he became an "object of hatred for that generation of Confederate writers." (Thomas L. Connolly and Barbara L. Bellows, God and general Longstreet: a lost cause and the Southern mind, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University press, 1982, 32ff.) His reputation was later restored as historians reevaluated Lee's strategy.

The Third Day: July 3

The third day of Gettysburg was the turning point of the war in the East. Jeb Stuart had arrived late in the evening of the second day, pleased to report that he had captured a train of Union supplies. General Lee was not impressed: Union supplies were of little use to him at that point. Because the inevitable confrontation between Lee and Stuart took place in private, it is not known exactly what was said. What is known is that Lee, despite the feelings of some of his generals that Stuart should be court-martialed, knew that his bold cavalry commander was too valuable to lose.

Perhaps realizing that so far he had committed much and gained little in this campaign, and that Confederate forces were beginning to run out of resources, Lee decided to gamble on one great, bold stroke. He would attack directly into the center of the Union line, using George Pickett’s fresh division supported by a division from Ewell’s corps. General Meade, a thoughtful if not in brilliant general, concluded that Lee, having tried the flanks unsuccessfully, would attack the center. With Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps in the center of the Union line, Meade was confident.

Shortly after noon on July 3rd General Lee’s artillery opened up a furious barrage designed to weaken the Union defenses along Cemetery Ridge. Thus began the greatest artillery duel ever conducted in the Western Hemisphere. It is reported that as the wind shifted during the afternoon, the rumbling of the cannon could be heard as far away as both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Whether that is true or not, the smoke, fire and noise that erupted were never forgotten by the troops who were present that day. Because of the smoke raised, it was difficult for the gunners to determine the effectiveness of their artillery fire upon the enemy. Thus Lee’s artillerymen were unaware that much of their shot was passing over the Union lines and landing in the rear, where it did considerable damage to supplies and other rear echelon elements, but had little impact on the troops who were preparing to defend against the assault. Union artillery, meanwhile, ceased firing to replace round shot with canister, turning their artillery pieces into what might be called overgrown shotguns in anticipation of the infantry charge.

Shortly after noon on July 3rd General Lee’s artillery opened up a furious barrage designed to weaken the Union defenses along Cemetery Ridge. Thus began the greatest artillery duel ever conducted in the Western Hemisphere. It is reported that as the wind shifted during the afternoon, the rumbling of the cannon could be heard as far away as both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Whether that is true or not, the smoke, fire and noise that erupted were never forgotten by the troops who were present that day. Because of the smoke raised, it was difficult for the gunners to determine the effectiveness of their artillery fire upon the enemy. Thus Lee’s artillerymen were unaware that much of their shot was passing over the Union lines and landing in the rear, where it did considerable damage to supplies and other rear echelon elements, but had little impact on the troops who were preparing to defend against the assault. Union artillery, meanwhile, ceased firing to replace round shot with canister, turning their artillery pieces into what might be called overgrown shotguns in anticipation of the infantry charge.

When the smoke finally cleared General Pickett’s division, some 15,000 strong, marched out of the woods to the music of regimental bands, with bayonets glistening, and arrayed themselves in an impressive line stretching along the front edge of Seminary Ridge. Union troops on Cemetery Hill were awed by the spectacle, but they were determined to redeem their losses at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. The men of the Army of the Potomac were not intimidated. Union artillery, stocked with canister, moved their guns into position to fire directly into the advancing troops.

The objective of Pickett’s men was a copse of trees, still very prominent on the Gettysburg battlefield to this day. As his troops began to march, converging on that objective, they passed through a relatively low area, across a road and a wooden fence and then advanced up the slope toward the Union lines. When they were within range, Union riflemen and artillery let loose a furious volley of shot that tore great holes in the Confederate line. Nevertheless, the courageous Southern soldiers pressed forward until a small group of them, perhaps a few hundred, reached a stone wall at the front of the Union line. Scrambling over the wall, they engaged the Yankees hand-to-hand, using rifle butts, bayonets, fists—anything that might bring an enemy down—in a few minutes of furious combat. But the damage had been too great, and the Confederate soldiers inside the Union lines who were not killed or wounded were soon captured. The remnants of Pickett's division stumbled back toward Seminary Ridge. It is reported that General Lee rode out on his horse and confronted General Pickett, feeling that his division commander should try to organize an orderly retreat. “General Pickett,” he is supposed to have said, “you must see to your division.” The shattered General Pickett replied, “General Lee, I have no division.”

Thus ended three days of fighting that produced over 50,000 casualties on both sides. There was no fighting on July 4; both sides needed to recover. Lee began a painful evacuation back to Virginia with wagon trains of wounded soldiers moaning in their pain. President Lincoln, feeling that another opportunity had been lost to crush Lee's army once and for all, wrote an angry note to General Meade deploring his failure to pursue Lee. Rather than sending the note, however, the president held it and later concluded, “How can I criticize a man who has done so much for doing too little?”

There was no more major fighting in eastern sector in 1863. The destiny of the South was still being played out in Mississippi and Tennessee.

Vicksburg: The Decisive Turning Point

The City of Vicksburg occupies a steep bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. In 1863 the city was well fortified by state-of-the-art fortifications and heavy cannon. Sometimes known as fortress Vicksburg, the city stood across the Mississippi from the terminus of a railroad line that brought Texas beef and other supplies as well as military equipment smuggled into Texas from Mexico. Mexican ports were not affected by the American blockade. Another railroad line left Vicksburg and stretched through Jackson, Mississippi, and back to the Eastern theater. The Vicksburg fortifications kept the Mississippi essentially closed to Union traffic north and south of the city.

The Vicksburg garrison numbered about 35,000 men under the command of Confederate General John C. Pemberton, a Pennsylvanian who was married to a woman from Virginia. To the north of the city stood Chickasaw bluffs, a steep, wooded approach that could be accessed only by going through the messy Chickasaw Bayou. To the south were more steep cliffs, also well protected. Approaching the city from the river side would have been well nigh impossible.

Starting in the fall of 1862, Grant began trying various strategies to capture Vicksburg. From his base in Memphis Grant set out to approach Vicksburg by an inland route through a supply base which he established at Holly Springs in northern Mississippi. But cavalry raids by Nathan Bedford Forrest and Earl Van Dorn repeatedly disrupted Grant’s supply lines, and he was forced to withdraw. Grant then tried sending gunboats and transports through the swamps and bayous on both sides of the Mississippi, but often found the waterways thick with overhanging branches and channeled through swampy ground. Progress was slow, and Confederate sharpshooters could easily harass attempts to cut a path through the natural barriers. In early 1863 Grant even had General Sherman’s men try to reroute the Mississippi River though “Grant’s canal,” a ditch across a neck of land in a bend in the Mississippi opposite Vicksburg. None of those approaches worked, and Grant knew he had to find a way to get at the fortress city from the eastern land side.

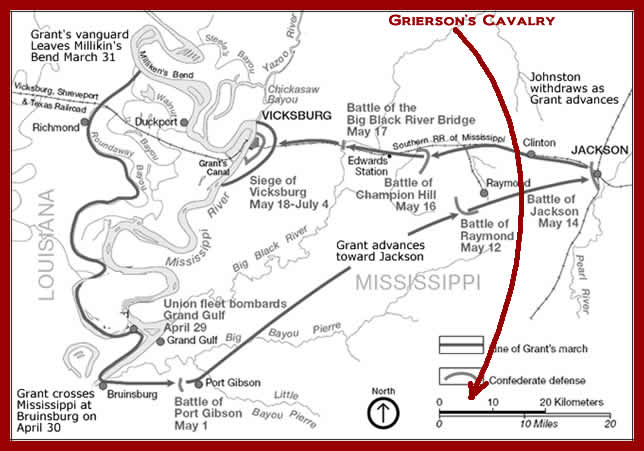

The result of Grant’s planning was what Civil War historians have accurately called the most brilliant campaign of the Civil War. Grant had Flag Officer Foote float his gunboats and transports down the Mississippi without power during a dark night; most of them made it. Then Grant marched his entire army South along the west bank of the Mississippi past Vicksburg, crossed the river at Bruinsburg, and set out for Jackson, about 40 miles to the east. Grant commandeered all the wagons he could find and took his supplies with him, cutting off communication with the river (and with Washington) as he headed northeast.

In the meantime Grant had directed Colonel Benjamin Grierson to take a cavalry force from Holly Springs through the area around Jackson and down to Baton Rouge. Grierson led three regiments of cavalry, about 1,700 troops, 600 miles in a little over two weeks. They tore up railroad tracks, cut telegraph wires, destroyed bridges, warehouses and railroad equipment and generally raised hell, occasionally making feints to distract Confederate pursuers. (A few of the more adventurous of Grierson’s men also “liberated” a quantity of Southern whiskey while en route; some of them had to be tied onto their saddles.)

Grant fought his way to Jackson, rolling over outnumbered defenders, as Pemberton could not send the entire Vicksburg garrison in pursuit of Grant. Securing his rear at Jackson, Grant then turned toward Vicksburg’s defenders, who had come out to meet him. After winning a battle at Champion’s Hill, he drove the Confederates relentlessly back into the city. His attempts to storm the garrison, however, failed, and Grant settled into a siege which lasted 45 days. When Pemberton found his men, as well as the inhabitants of the city, desperately short of supplies and under constant bombardment from Grant’s artillery, he had no choice but to surrender. Pemberton turned over the city and its garrison on July 4, 1863, one day after Lee’s troops were turned back in Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg.

President Lincoln, who had grown up in the Mississippi Valley and understood the significance of the capture of Vicksburg, sent a telegram of congratulations to Grant. He is said to have remarked, “Once again the father of waters flows unvexed to the sea.” The double blow of Gettysburg and Vicksburg crippled the South and set the stage for the final phase of the war.

The New York City Draft Riots. Despite the victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg President Lincoln could not rest easy throughout the summer and fall of 1863. The combination of the Emancipation Proclamation and the draft system, which placed the burden of the continued fighting mostly on working-class men, led to discontent, especially among the Irish working-class people in New York City. Fearing that liberated slaves might threaten their economic well-being, and disgruntled over the implications of the draft, workers fomented a riot in New York City to show their discontent with the war and emancipation.

Rampaging through black neighborhoods they set fires and beat or terrorized African-Americans. Eleven men were murdered by lynch mobs, and the riots were only quelled when federal troops were sent from Pennsylvania to the city. Although the naval bombardment depicted in the recent film Gangs of New York did not occur, federal troops used artillery against the rioters, who numbered in the thousands.

The Copperheads. Lincoln’s problems did not end with the suppression of the New York race riot. Political opposition to Lincoln's wartime policies was headed by a group of disgruntled Democrats, called Copperheads by their Republican opponents. Although members of the movement did not have a unified agenda, they were opposed to the war, and many of them thought it was being fought to free the slaves and destroy the South. Some of the same motives that propelled the New York rioters were present among the Copperheads, who were politically very active. Lincoln did not hesitate to deal forcefully with dissenters whom he felt were hurting the Union cause. He suspended habeas corpus and had thousands of dissenters jailed under martial law. He placed saving the Union above scrupulous adherence to constitutionally guaranteed liberties, an act for which he has been criticized.

The most famous copperhead was Clement L. Vallandigham, an Ohio politician who made speeches openly critical of Lincoln and his policies. Accused of disloyalty in time of war, Vallandigham was court-martialed, convicted and eventually given free passage through Confederate lines to Canada, whence he ran for governor of Ohio. He was defeated in a pro-war landslide, but his Democratic supporters managed to get a Copperhead platform accepted during the 1864 presidential election. General George B. McClellan, the Democratic nominee for president, did not accept the Copperhead agenda and was pro-war, though Lincoln feared the ultimate result if McClellan were elected, as the Copperhead movement was a serious threat to the Union cause.

Chickamauga. In September 1863 the battleground shifted to southeast Tennessee and northwestern Georgia. General Longstreet, whose Corps had been detached from Lee's army, joined forces with General Bragg and attacked Union forces south of Chattanooga along Chickamauga Creek. The Union Army was spared a disastrous defeat by the bravery of General George H. Thomas and his brigade, who stood their ground long  enough to allow the Union Army to make an orderly retreat into Chattanooga. For his performance Thomas became known as the “Rock of Chickamauga,” and his brave soldiers the Chickamauga brigade. (Thomas Circle in Washington, DC, is the location of General Thomas's statue.)

enough to allow the Union Army to make an orderly retreat into Chattanooga. For his performance Thomas became known as the “Rock of Chickamauga,” and his brave soldiers the Chickamauga brigade. (Thomas Circle in Washington, DC, is the location of General Thomas's statue.)

Since the Federal troops in Chattanooga suffered from supply shortages and poor morale, General Grant was directed to proceed to Chattanooga to take charge. Grant arrived inauspiciously, purchased a horse from a local stable, and rode out to the Union headquarters. Calling the commanders together, he asked each to outline for him the disposition and condition of his troops. He sat listening quietly and when he had heard enough, he began writing out orders for each commander on a notepad. Distributing the written instructions, he told his officers that they had their orders and sent them on their way. Within two days supply lines had been opened and troop morale began to return.

Chattanooga. In November 1863 the last major battle of that decisive year was fought at Chattanooga. Grant’s corps commanders, Generals Hooker, Sherman and Thomas, engaged Bragg’s troops while Longstreet was carrying out a siege of Knoxville. Once again a corps commander, General Hooker took his men to the heights of Lookout Mountain which overlooks the city of Chattanooga and the Tennessee Valley. In an action that became known as the “battle above the clouds,” Hooker drove the Confederates off the mountain. He then raised the national flag at the summit, encouraging the troops below. (The cable car that takes visitors to the top of Lookout Mountain is the steepest in the world. The view from the summit is spectacular, especially when clouds lie in the valley and only the mountaintops are visible.)

Although Grant had ordered that there be no frontal assaults against well-defended Confederate positions, troops under Sherman and Thomas approaching Confederate defenses along Missionary Ridge took it upon themselves to assault the Confederate lines, feeling that they were vulnerable in the position they held at the base of the ridge. The assault was successful, and the battle resulted in Chattanooga, the “gateway to the South,” being fully in Union hands. One of the two major Confederate armies still in operation had been routed.

Summary of 1863. The three great Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga shifted the tide dramatically in favor of the Union, but the South was not yet defeated nor ready to surrender; soldiers on both sides prepared for another year of warfare. President Lincoln weathered political storms but was concerned about his reelection if the war did not become settled by the fall. Most important, Lincoln now knew he had a general who could fight, and he would soon appoint Grant to overall command of the Union armies. While Confederate General Lee still commanded great respect, dissension was rising among other top Confederate commanders.

As the third full year of fighting dawned, questions abounded. Grant had captured two Confederate armies numbering over 40,000 men. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had suffered huge casualties, not only at Antietam and Gettysburg but also in their victorious engagements. If the outcome of the Civil War was inevitable, one might ask, how was the South able to carry on in the face of such losses? At the same time one might ask how the men of the Union, and their women at home, remained willing to accept such sacrifice in the face of an enemy that seemed determined to continue the slaughter at all costs.

In his classic history of the Army of the Potomac, historian Bruce Catton, discussing the reasons why thousands of veterans whose three-year enlistments had expired in the early 1864 were willing to sign up for further service wrote that, “the dominant motive, finally, seems to have been a simple desire to see the job through.” The same sort of motivation drove Confederates to continue the struggle in the face of difficult odds. Both sides had invested an enormous amount of blood and treasure in the conflict, and it was difficult to cast aside such a costly investment and give up the fight. So the fight went on.

President Lincoln, finally realizing that he had found a general who could finish what others had started, brought Grant east to take command of all the Union armies. Lincoln awarded him the rank of lieutenant general, the first officer since George Washington to have been given that honor. Although Grant was warmly received in Washington, he did not take well to the political environment of the city and quickly made his way to the Army of the Potomac headquarters where he conferred with General Meade, who officially remained the Army’s commanding general. Grant went back to Washington for conferences, but when he returned two weeks later, the Army of the Potomac was for all practical purposes now Grant’s army. Waiting to take the measure of their new opponent were Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. The war was about to enter its final stage.

As commander of all Union forces, Grant was now able to devise a strategy that would take advantage of the North’s superior numbers and the South’s dwindling resources. General William T. Sherman had taken over command of the Army of the Tennessee and was prepared to move into Georgia. Grant’s strategy was to have his Army of the Potomac capture Richmond while Sherman captured Atlanta, then the two armies would execute a pincer movement on Lee’s army in Virginia. Grant assigned additional missions to other officers, Generals Butler and Sigel, but the focus of the final year of fighting was on Grant and Sherman.

Sherman's Campaign in Georgia and the Carolinas, 1864-1865

On May 7, 1864, Sherman set out from Chattanooga with armies commanded by Generals Thomas, Schofield, and McPherson. Remembered for his famous march through Georgia, Sherman’s reputation suggests that he was cold-blooded and ruthless. In fact Sherman was a very skillful commander who did not spill blood, neither his or the enemy’s, carelessly. In his movement from Chattanooga to Atlanta, Sherman avoided direct attacks on heavily defended positions and instead used flanking movements to advance in a less costly manner. Sherman surrounded the city of Atlanta and accepted its surrender on September 2. He ordered the city evacuated, and in a famous letter to the mayor and city council, he gave his reasons why he would not honor their request to rescind the order. Realizing that his demand for evacuation of the citizens was harsh, he nevertheless promised to “make their exodus in any direction as easy and comfortable as possible.” His response is regarded as a clear definition of what modern total warfare had become. He was sympathetic but blunt in his purpose: “You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.” (See full letter in Appendix.)

Sherman spent two months in Atlanta preparing for his “March to the Sea.” Keeping his promise to make Georgia howl, Sherman’s men cut a path across Georgia destroying everything of possible military value and much that was probably not. Although Sherman cautioned his men against unnecessary violence to civilians, the march was nonetheless harsh and brutal. Arriving outside Savannah shortly before Christmas, Sherman allowed a weak defending force to escape rather than fight what would surely be a losing battle.

Sherman spent two months in Atlanta preparing for his “March to the Sea.” Keeping his promise to make Georgia howl, Sherman’s men cut a path across Georgia destroying everything of possible military value and much that was probably not. Although Sherman cautioned his men against unnecessary violence to civilians, the march was nonetheless harsh and brutal. Arriving outside Savannah shortly before Christmas, Sherman allowed a weak defending force to escape rather than fight what would surely be a losing battle.

Sherman and his staff moved into the city, but the Army bivouacked outside and Savannah was left for the most part untouched. Several weeks later Sherman’s army crossed the Savannah River into the state which his men knew had been the source of all the rumpus, the first-to-secede state of South Carolina. Sherman’s march through Carolina was more fierce and brutal than his march through Georgia, but by that time Lee was in serious trouble in Virginia and was unable to help. Sherman captured the capital of Columbia in February 1865 and proceeded northward, planning to link up with Grant.

The Election of 1864. President Lincoln may have had reason to worry about being reelected, though his concern was less for his own political future than for the outcome of the war. He feared that if the Democrats won with their candidate, General McClellan, the Confederacy might be allowed to go its way with the Union permanently severed. All the sacrifices made to that point would then have been for naught. Lincoln rejected suggestions that the election ought to be postponed or canceled on the grounds that he was fighting to save a democratic society. Denying people the vote would controvert the purpose for which he was fighting.

Lincoln did, however, decide not to run as a Republican but rather on a National Union Party ticket. (The Republican Party changed its name for the election.) He replaced Vice President Hannibal Hamlin with Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, a Southern Democratic senator who had remained loyal to the Union. Lincoln instructed that all soldiers who could be spared should be allowed to return home to cast their votes. Some states allowed their soldiers to cast their votes in the field. Those who were able to do so voted overwhelmingly for the president over the general who had formerly commanded many of them. The same sentiment that had propelled many soldiers to extend their service also worked for Lincoln—his fighting men wanted it to see the job done.

As late as August, 1864, the election may well have been in doubt, for Grant’s Virginia campaign was proving to be extremely costly. But Sherman's capture of Atlanta, a major Southern city, in September gave renewed hope for a successful conclusion to the conflict to the northern people, and they reelected Lincoln by a comfortable margin. He won 55% of the popular vote and captured the electoral college by 212 to 21.

From the Wilderness to Appomattox Court House

About the time that Sherman was beginning his march into Georgia, Grant attacked Lee west of Fredericksburg in the Battle of the Wilderness. The thick foliage caused confusion, and soldiers had difficulty distinguishing friend from enemy in the smoking undergrowth. After a few days of indecisive but bloody combat, the veteran Union troops expected to return to bivouac once again and wait for the next assault. But Grant had other plans; he wired back to Washington that he intended “to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Grant’s army engaged Lee in a series of frustrating and costly flanking movements that took the two armies from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor, a position east of Richmond. Grant's army suffered 60,000 casualties in one month, earning him the epithet of “butcher.” But Grant knew that he could eventually win the series of battles by grinding down Lee’s depleted forces with his own superior numbers and resources.

Grant directed to some of his subordinate commanders to advance on Petersburg, hoping to take the city and prevent Lee from using it as a base. The Federals failed to take Petersburg, however, in four days of fighting, and a nine month siege began. Lee’s army was now bottled up in Richmond and Petersburg, and Union attempts to breach the Confederate lines failed. The conclusion would have to wait for the spring of 1865.

Last-Ditch Diplomacy. There can be little doubt that the initial cause of secession was slavery and that to a certain extent the war was being fought on that account. Yet, the three years of bitter fighting had shifted Southern sentiments, and the goal of the Confederacy by late 1864 was getting out of the Union at any cost. It was conceivable to many that gaining independence might even require abandoning the institution of slavery. Although the idea of emancipating or arming the slaves alarmed many in the South, a number of officers and politicians thought the idea worthy of consideration.

In December 1864 Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin and President Jefferson Davis authorized a mission to Great Britain and France with a proposition to offer abolition of slavery in return for recognition of Southern independence and assistance. Although the mission was unsuccessful, the potential value of freeing slaves to fight was powerful. In February 1865, the Confederate House of Representatives authorized President Davis to enlist black soldiers from the Southern states. Although Southern newspapers and politicians acknowledged that slavery had been a cause of the war, many argued that it was time to give it up in order to achieve independence. The movement came too late; by that time the Confederacy was lost.

In November and December 1864 Confederate armies under the command of General Hood moved into Tennessee in one last desperate offensive assault. The first action took place at Franklin, some 15 miles south of Nashville. The federals were forced to retreat, but Hood had suffered large heavy casualties. On December 15 and 16 General Thomas attacked the advancing Confederates and drove Hood’s men out of Tennessee all the way to Mississippi. The last Confederate offensive action of the war ended in a crushing defeat.

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in for his second term as president and gave a brief inaugural address. Considered by many his finest address, it is inscribed on one wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Acknowledging that slavery was the cause of the war, he said:

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope fervently do we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bondman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be stink, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

He ended on a conciliatory note, urging for the entire nation to bind up its wounds “With malice toward none; with charity, for all” to ensure a “just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” (See entire address in Appendix.)

The Final Campaign. During the course of the winter, Grant’s Union army had been fighting their way around to the western side of Petersburg in order to cut off the last roads and the last railroad into the city. Although Sherman was rapidly approaching Lee’s rear, Grant was determined to finish the business himself. He sent cavalry under Philip Sheridan and the V Corps of the Army of the Potomac around to the west of Petersburg to attack Lee’s right. Lee's depleted Army could not stave off the Yankee assault as Grant ordered an advance all along the line.

On a Sunday morning in April, while at St. Paul's Church in Richmond for services, President Davis received a telegram from General Lee indicating that the city must be abandoned. The Confederate government packed records and the treasury’s remaining gold on the last trains and headed out of the city. They set fire to everything of military value in Richmond, and with the departure of the army and the government, frustrated Southerners joined in the destruction of their capital. Union soldiers entered the city the next morning and their first business was to put out the fires and restore order.

On a Sunday morning in April, while at St. Paul's Church in Richmond for services, President Davis received a telegram from General Lee indicating that the city must be abandoned. The Confederate government packed records and the treasury’s remaining gold on the last trains and headed out of the city. They set fire to everything of military value in Richmond, and with the departure of the army and the government, frustrated Southerners joined in the destruction of their capital. Union soldiers entered the city the next morning and their first business was to put out the fires and restore order.

As Lee was attempting to escape to the West, President Lincoln visited Richmond, where he was surrounded by blacks shouting “Glory to God!” and “God bless Father Abraham!” Lincoln was overcome with emotion as he told one black man kneeling in front of him to get up again, that he did not have to kneel before anybody except God.

Lee’s desperate attempt to escape Grant’s army was doomed to failure. Now outnumbered by the Union army by about four to one, Lee’s famished men tried to reach a supply train near Danville, but they were cut off by Sheridan’s cavalry and the Union’s V Corps, whose 1st Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain. Two more corps were closing in on Lee. He reluctantly concluded that the only course left of him was to request a meeting with General Grant. On April 9 Lee formally surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Courthouse. For all practical purposes, the Civil War was over. (For a moving account of the last days of the war and the surrender of Lee's army, see Joshua L. Chamberlain, The Passing of Armies: An Account of The Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, New York: Bantam, 1992. Major General Chamberlain accepted the surrender on behalf of General Grant. Chamberlain had been badly wounded at Cold Harbor, and his death was erroneously reported in Maine newspapers.)

President Lincoln Assassinated

Feeling that his four-year nightmare had come to an end, President Lincoln was able to relax for the first time since his inauguration. On April 14 he and his wife attended a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. John Wilkes Booth, an actor who was familiar to the staff of the theater, made his way to the president’s box and shot him in the back of the head. Mortally wounded, Lincoln died the next morning, which was Good Friday. While many in the South were cheered by the death of the man they considered to be a tyrant, the North mourned its fallen leader. Thousands lined the tracks as Lincoln’s funeral train made its way back to Springfield, Illinois. As even some Southerners recognized, Abraham Lincoln would certainly have presided over a generous Reconstruction era, but that was not to be. Winston Churchill wrote in his History of the English Speaking Peoples, “The assassin’s bullet had wrought more evil to the United States than all the Confederate cannonade.” He added:

Thus ended the great American Civil War, which must upon the whole be considered the noblest and lease avoidable of all the great mass-conflicts of which till then there was record.

Within a few weeks of Lee’s surrender the remaining Confederate military units surrendered. President Jefferson Davis was captured in Georgia by a Union cavalry force that had traveled at will through the South. There were no settlements or negotiations; the Union had never recognized the independence of the Confederacy, so there was no need for any sort of treaty. The only issue was how to restore the former Confederate States of America to their proper place within the United States.

The impact of the terrible war on both the North and South was barely calculable. The fighting had produced approximately one million casualties, including over 600,000 deaths from all causes. The impact on the Southern economy had been devastating; shortages produced by the blockade and the printing of paper currency had led to drastic inflation in the Confederacy. The South also faced a badly deteriorating railroad network and shortages in labor, capital, and technology. Millions of dollars of value in property, including that of slaves, had simply evaporated; the economic recovery of the South would be a struggle for both the black and white population for decades to come.

Women in the Civil War. As was true in the American Revolution, women on both sides assumed responsibilities that had once been the province of their departed husbands, fathers, sons and brothers. They managed farms, plantations and businesses, and in the North women took jobs in industry and government. Women were especially valuable in areas such as textiles and shoe making, helping to provide millions of articles needed by the soldiers. Many northern women enlisted in the Army Medical Corps, and the profession of nursing was advanced markedly through the efforts of women such as Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix. Florence Nightingale had become the British “angel of the battlefield” during the Crimean War, and her example spurred American nurses to carry their skills into areas formerly the sole province of men.

As has been true in other American wars, women were expected to do their part in keeping up the morale of the troops on the front line. Thousands of letters written from soldiers to their families, both North and South, as well as the families’ responses, have been collected and published. Historian James McPherson and others have done extensive research in collections of letters in order to better understand issues surrounding the war. Although difficult to measure, the impact of attitudes of the people at home certainly affected behavior on the battlefield. In the South, especially in the last year of the war, frustrations raised in places where Yankee armies had stormed through the country more or less unopposed were transmitted to soldiers directly; lonely and frightened women sometimes encouraged their husbands to desert and come home and take care of them.

An unknown number of women also fought in the Civil War on both sides. Since they had to disguise themselves and keep their sexual identity secret, records of female participation on the battlefield are virtually nonexistent. What information we have is mostly anecdotal, but it is nevertheless interesting. A woman who served with Grant at Vicksburg has become something of an icon for feminist historians. She fought as Private Albert D.J. Cashier, but had been born Jennie Hodges in Ireland. Wanted to keep her secret, she lived out the rest of her life as a man, and her true identity was discovered only when she was near death in an old soldiers’ home in Illinois.

Many women kept journals and diaries during the war, and those writings and the letters they wrote to soldiers and to friends tell us much about conditions in the North and South during the war. The last line of John Milton’s poem “On His Blindness,” is often cited to underscore roles of women in wartime: “They also serve who only stand and wait.” Yet in the Civil War, as in virtually all of America’s, many women did far more than stand and wait.

Financing the War. Generally speaking, the North handled wartime finances reasonably well, despite much corruption and waste. The Federal government raised taxes, sold bonds and printed “greenbacks”—paper money not backed by gold or silver that was supported by a “legal tender” act, meaning that the government paper currency had to be accepted for all debts public and private. The new taxes included the first federal income tax, higher tariffs, and taxes on almost every known commodity. The North did suffer a modest inflation during the course of the war, and widespread fraud occurred in the procurement of equipment, supplies and food for Union armies, a phenomenon that seems to recur in wartime with regularity. Yet, except for a brief period of financial panic before Congress took action in 1861 and 1862, the federal economy remained remarkably stable.

In the South, because financial resources were depleted more rapidly than in the North, Confederate paper currency soon became devalued, and rampant inflation a hundred fold greater than in the North ruined the Southern economy and hampered the war effort. The South managed to procure much in the way of vital supplies through blockade runners, though owners of those ships often tried to maximize profits by smuggling in luxury items such as perfume along with gunpowder and rifles. At the end of the war, when Confederate money and bonds were invalidated, millions of dollars of paper wealth evaporated.

Wartime Politics. The Copperhead movement in the North, mentioned above, threatened Lincoln’s management of the war and weakened the armies by encouraging men to desert. But the absence of a strong Democratic Party in Congress gave the Republicans an opportunity to pass legislation that might otherwise have stalled. The result was one of the most prolific periods of legislation in American history; the Republican pro-growth, pro-business Congress paved the way for postwar capitalist expansion.

Two laws passed in 1862 would have an enormous impact when the war ended by encouraging development of the West. The Homestead Act of May 1862 granted any family head over 21 years of age 160 acres of public land, the major requirement being that the owner would have to live on the land for five years and develop it. Additional land could be obtained at very low prices. In order to improve transportation in those vast unsettled areas, Congress passed a series of Pacific Railway acts beginning in 1862. The acts provided for huge land grants along proposed rights of way and loans for railroads which could be repaid at a comfortable interest rate. In the end, railroad companies received over 200 million acres of land from both federal and state land grants, enabling construction of the first transcontinental railroad to continue.

Another 1862 act, the Morrill Act, provided thousands of acres of land to the states for construction of colleges and universities for the furtherance of the agricultural and mechanical arts. At the same time Congress created the Department of Agriculture. The result of the Morrill act was the creation of many first-class universities across the nation, including some whose names, such as Texas A&M, reflected the purpose of the act. The impact of this significant legislation would, of course, not be realized until the fighting had ended, but the impact of these laws would carry well into the 20th century.

Jefferson Davis also faced political strife, but it played out differently for him than for Abraham Lincoln. With a vigorous two-party system still alive in the North, Lincoln was able to take criticism of his government and policies by his political opponents as traditional responses of the “loyal opposition” even when that opposition was not necessarily loyal. With the Southern one-party system, however, Davis tended to take criticism personally. He was less skillful in absorbing the barbs than Lincoln, whose patience sometimes tried even his most loyal supporters. Davis was further hampered by the states rights philosophy of the South, which occasionally produced a sort of knee-jerk reaction to Confederate federal policies.

Wartime Diplomacy. For some historians, it is virtually a given that if Great Britain or France had recognized Confederate independence and entered the war, Southern victory would have been assured. Lincoln was well aware of that fact when he apologized to the British over the Trent affair, recognizing that British involvement could only bode ill for the Union. Two factors worked in Lincoln’s favor regarding British involvement. Alternative sources of cotton in Egypt and India made British reliance on Southern cotton for her textiles factories less urgent. And British working class objection to Southern slavery gave pause to the government, especially following the Emancipation Proclamation, when British support for the South would seem to some like support for slavery.

The service of the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, Charles Francis Adams (son of John Quincy), cannot be overlooked. His skillful diplomacy kept his government well informed of possible British actions, and effectively neutralized potential conflicts that might have changed the British position vis-à-vis recognition of the South. The tension between the Lincoln government and the British came to a head in the summer of 1863 over the Laird Rams controversy.

James Bulloch was a Confederate agent and an experienced naval officer who made his way to Great Britain in 1861 and began to contract for the building of warships for use by the Confederacy. Two of those, the C.S.S. Alabama and C.S.S. Florida, became famous commerce raiders and did substantial damage to Union merchant shipping. When Bulloch negotiated with the Laird shipbuilding company for construction of a number of ironclad rams designed to break up the Union blockade fleet, Adams lodged repeated protests with the British foreign office. In one note he suggested to the British foreign secretary Russell, “It would be superfluous in me to point out to your Lordship that this is war.” The British government had already decided to back down, but the successful outcome of the confrontation nevertheless made Adams a hero. (Incidentally, James Bulloch’s sister, Martha (Mittie) Bulloch was Theodore Roosevelt’s mother.)

Despite some initial blundering, as when he suggested to President Lincoln that the United States might restore the Union by starting a foreign war (a suggestion which the wiser president simply ignored), William Seward proved to be an effective Secretary of State. When the government of Napoleon III began an imperial adventure in Mexico, the United States government refused to recognize his authority and sent troops to the Mexican border as a warning. Napoleon’s folly was soon undone as his appointed emperor of Mexico, Archduke Maximilian, was quickly deposed.

In the end, the hope for recognition of Southern independence which might mirror French recognition of American independence in 1778 never came to be. Just as it can be claimed that had the French not intervened, the outcome of the American Revolution would likely have been very different. Thus it may be asserted that any such recognition on behalf of the Confederacy certainly might have changed the outcome of the Civil War. In that regard, the value of the service of Ambassador Adams cannot be overstated.

The Legacy of the War. The American Civil War, or war between the states, remains at the center of American history. The loss of over 600,000 lives and the destruction of untold millions of dollars in property was felt for generations. While the end of slavery was the most visible change on the face of America, numerous other transformations made the United States a very different nation in 1865 from what she had been in 1860.

On the negative side, the bitterness and hatred that would last for generations was an unsurprising outcome of the terrible conflict. In the North, smoldering resentment over the concept of the rich man’s war and the poor man’s fight would erupt in what became known as the war between capital and labor in the decades before 1900. Workingmen would prove to be just as willing to shoot a company hired guard or strike-breaker as they had been to shoot a rebel or a Yankee. Labor violence would continue well into the 20th century.

In the South, where the bitterness was understandably far greater than in the North, the former slaves were predictably made scapegoats for the war and its outcome. Random violence against Freedmen began almost as soon as the war was over and continued with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacy organizations. The Civil War and its immediate aftermath, the Reconstruction Era, were huge milestones in the progress toward America's goal of “liberty and justice for all.” Nor was all the bitterness directed against blacks; whites who had openly opposed secession, or who had failed to support the Confederate cause with sufficient enthusiasm, were often targets of ostracism and even violence during the postwar years. In addition, Northerners who came South after the war for various reasons, some of them good, were labeled “carpetbaggers” and were often abused.

A measure of the bitterness generated in the South can be seen in the words of a woman of Richmond, who wrote in her diary, “When the Yankees raised the American flag over the capitol, tears ran down my face, for I could remember a time when I loved that flag, and now I hated the very sight of it.” On hearing news of President Lincoln’s assassination, a woman in Texas exulted over the fact that the most bloodthirsty tyrant who ever walked the face of the earth was gone, and she hoped he would “burn in hell” all through eternity. Bitter Southerners vowed to continue to hate Northerners and to raise their children to hate Northerners. One of my students, a Northerner, once claimed that when she married a Southern man, it took her twenty years to figure out that “damn Yankee” was two words. Recent struggles over the displaying of the Confederate flag and other racially motivated disturbances suggest that the legacy of the Civil War, though perhaps fading in the 21st century, is still alive.

| Civil War Home | Updated June 20, 2017 |