The New Republic:

The United States, 1789-1800,

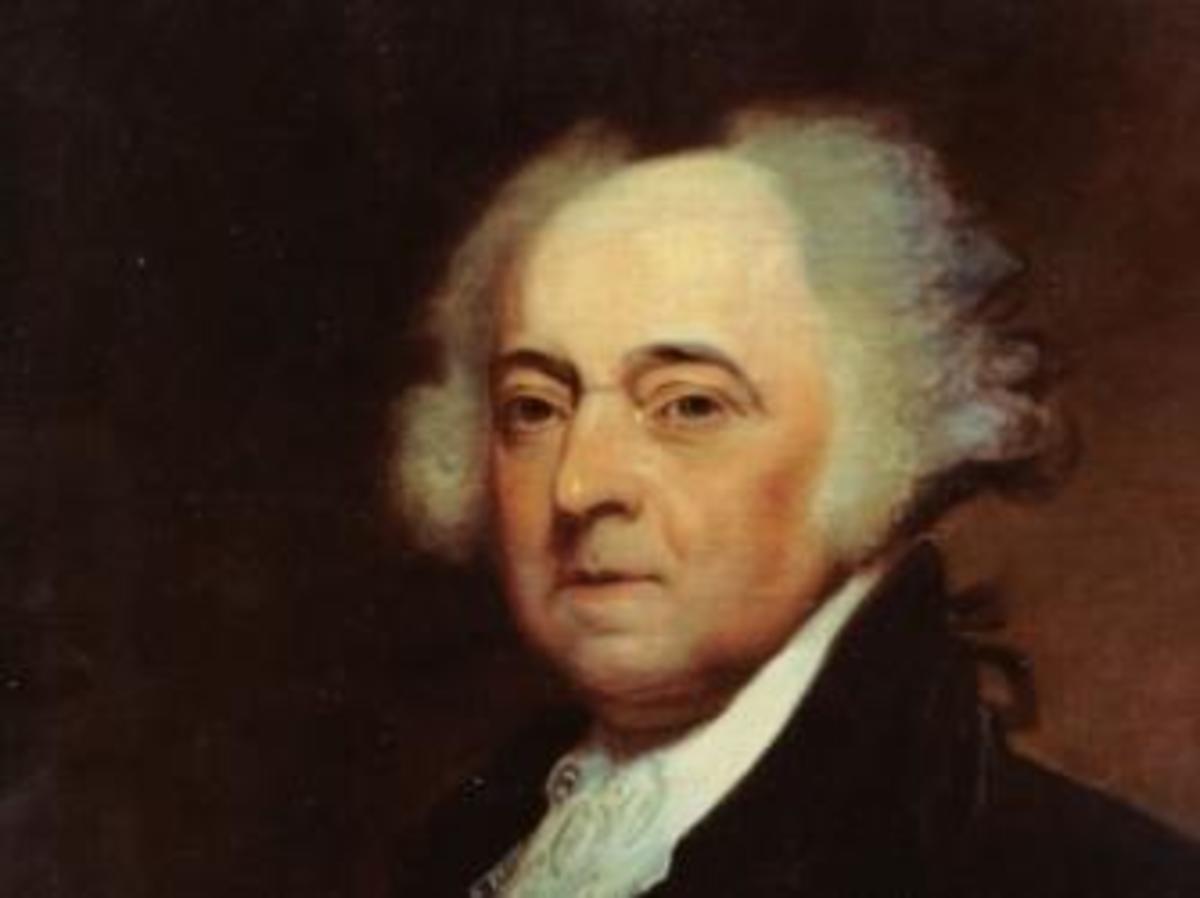

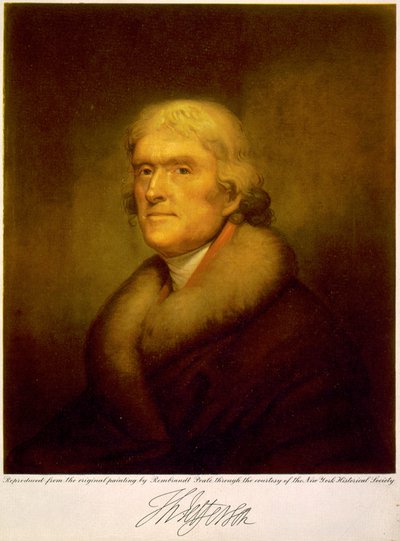

Part 2 The Election of 1796. Whoever was chosen to follow in the footsteps of the “Father of his Country” was bound to face challenges. Alexander Hamilton was far too controversial to get the nomination, but his influence was still very strong within the Federalist party. His attempt to manipulate the election of May 1796 backfired, which John Adams, the combative, argumentative revolutionary, a brilliant political thinker whose knowledge of the law was exceeded by few, lacked a personality conducive to running a smooth administration. Even with Abigail as his loving and trusted adviser, he felt the stings of political attacks very sharply, and had difficulty holding his temper. He made a tactical mistake by retaining Washington’s cabinet out of fear of offending his predecessor. He would have been better served by selecting his own men, especially as Hamilton had ties with the cabinet that facilitated his attempts at manipulation. Nevertheless Adams managed the difficult years of his presidency with considerable skill, at one point threatening cantankerous Federalists in Congress with resignation, suggesting they might have a much harder time dealing with Vice President Thomas Jefferson, who by then had made it clear that he opposed many of Adams’s Federalist policies. (Until the Constitution was amended in 1804, the winner in the Electoral College became president and the runner-up vice president.) Perhaps because of his rather cantankerous attitudes and stubbornness over issues in which he believed, he was not reelected in 1800. Yet he was in unfailingly decent and honest man, who deserve to be reelected, although Thomas Jefferson was also deserving. THE XYZ AFFAIR During the first years of Adams’s presidency, relations between the United States and France steadily deteriorated. The problem was aggravated by Jay’s Treaty, which angered the French, who took it as directed against them. When President Adams named Charles Cotesworth Pinckney as minister to France in 1796, the French refused to receive him. President Adams then sent a commission to Paris to attempt to gain a new treaty, sending John Marshall and Elbridge Gerry to join Pinckney. Although the Americans were greeted unofficially, before negotiations could begin, they were informed by three agents of French Foreign Minister Talleyrand, identified in reports as Ministers X, Y, and Z, along with a beautiful woman who may have been sent to distract and perhaps spy on the Americans, that negotiations were delayed. They were then informed that for talks to begin, France would need a bribe of $240,000 and promise of a loan. John Marshall replied firmly that no bribe would be forthcoming, and he and Pinckney left, leaving Gerry behind, as they were told that unless one of the three stayed, France would declare war. President Adams informed Congress of the failure, and when criticism erupted, he “laid the correspondence on the table.” Americans rose in anger, declaring “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.” Some Federalists called for a declaration of war, but Adams pursued a peaceful approach, though he called for the raising of an army, with Washington in command, reorganized the navy, and reconstituted the marine corps. Tensions continued to rise as Congress authorized privateers to seize French ships. A state of war known as the “Quasi-War” began and lasted for two and one-half years. The First Test of State v. Federal Rights: The Alien and Sedition Acts The Federalists used the outpouring of anti-French sentiment in America as an excuse to increase the nation’s military defenses, a move intended to stifle internal political opposition as well as thwart French aggression. The extreme Federalists secured legislation to build up the army, even though there was no prospect of a French invasion. The Federalists intended to use the army to stifle international opposition. With Washington in nominal command, Alexander Hamilton took over day-to-day control of the army and filled it with officers loyal to himself. All Hamilton needed was a declaration of war against France, but Adams refused to ask for one. In order to thwart open criticism of their actions, but purportedly to protect American security, the Federalist Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. The Acts were, in reality, Federalist measures designed to harass Republican spokesmen by disallowing criticism of the government. These blatantly political attempts to silence opposition ultimately proved counterproductive.

The Alien Enemies Act and the Alien Act gave the president power to expel any foreigner. The Naturalization Act required immigrants to reside in the United States for fourteen years before becoming eligible for citizenship. The Sedition Act made it a crime to criticize the government, and federal courts became politicized, often enforcing this law in absurd ways. Republicans were convinced that free government was on the brink of extinction. Although the Sedition Act was later declared unconstitutional and repealed, Republican newspaper editors and writers were fined or jailed. The Alien Acts were never used. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolves Jefferson and Madison responded to the Alien and Sedition Acts with the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798). The Kentucky Resolutions, written by Jefferson and passed by the state of Kentucky, claimed each state had the power to decide whether acts of Congress were constitutional and if not, to nullify them. Madison’s Virginia Resolutions urged the states to protect their citizens but did not assert a state’s right to nullify federal law. Jefferson and Madison were less interested in constitutional theory than in clarifying the differences between Republicans and Federalists. The resolves were the first shot taken at the right of a state to nullify federal laws and were a step in the long-lasting battle over states’ rights. Some threatened open rebellion if the acts were not repealed. Republicans could not take the case to court because they hated the courts and did not want to give them any more power. The situation was another example of the Constitution being seen as an experiment—far more fragile than we realize today. Nullification and even secession were spoken of long before the Civil War. Adams's Finest Hour: Avoiding Another War The 1778 treaty of alliance between France and the United States called for the United States to defend French possessions in the Caribbean region. For several years the French had been engaged in a war against Great Britain and the Netherlands, who had commercial interests in the Caribbean. The Neutrality Act of 1794 had canceled military obligations left over from the 1778 treaty. Although France accepted the idea of American neutrality, French ships were allowed in American ports, and other accommodations were made to the French. Because of the Jay Treaty, the international situation was complicated, and the French Navy began attacking American ships in the West Indies. All that led to the quasi-war with France of 1798–1800, and some voices in America demanded a declaration of war against France, which Adams refused.. Having refused to ask Congress for a formal declaration of war against France, Adams pursued peaceful negotiations. The Convention of Mortefontaine ended the Quasi-War and restored good relations between France and the United States. In 1799 Adams openly broke with Hamilton. The president sent another delegation to negotiate with France, and this delegation worked out an amicable settlement. The war hysteria against France vanished, and the American people began to regard Hamilton's army as a useless expense. In avoiding war with France, Adams saved the nation from the schemes of the High Federalists. In return, they made sure he lost the election of 1800. The Convention of 1800 finally cleared the air with France as the United States agreed to assume $20 million in debts in exchange for abrogation of the 1778 treaty. The election of 1800 is perhaps most noteworthy for the peaceful transition of government leadership from one political party to the other, demonstrating that such a process could be accomplished without widespread confusion, villainy, or violence. The new president, Thomas Jefferson, tried to Republicans Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr challenged Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney for the White House in 1800. The Federalists had a number of strikes against them including the Alien and Sedition acts, the taxes that were raised to support the army that was seen as unnecessary, suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion, and Jay’s Treaty. When the final results were tallied, Jefferson and Aaron Burr each had seventy-three electoral votes. The election was then thrown into the House, still controlled by Federalists, and many of them threw their support to Aaron Burr. The election was deadlocked through thirty-five ballots until Hamilton finally convinced several reluctant Federalists that Jefferson was a lesser evil than Burr, and Jefferson was elected. The Federalists lost office in 1800 partly as a result of internal party disputes, but more importantly, because they lost touch with American public opinion. The Federalists also lost the election of 1800 because they were internally divided and generally unpopular. The Republicans won easily, but now they would have the responsibility to govern, and as many subsequent parties and candidates have discovered, it is one thing to win an election, quite another to govern effectively. For a time, at least, the Republicans would have it their way. Several points about Jefferson's election in 1800 are notable. First, Jefferson called the election a “revolution” because political power in a major nation changed hands with no bloodshed, a rare occurrence in the modern world. Only the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 could compare. Second, although it was not considered proper to “run” openly, Jefferson worked hard behind the scenes to get elected. The Federalists linked Jefferson to France, and Jefferson woeked to dispel thise fears. Third, a peculiarity existed in the Electoral College in that there was no distinction between presidential and vice-presidential electors: The resulting tie sent the election into the House. The Twelfth Amendment corrected the problem, and only one subsequent election was decided by the House of Representatives, the election of 1824. The Federalist contribution: The Federalists were out of power, but they had wrought a new Constitution and gotten it underway, a considerable feat. Thus ended the era of the American Revolution with the country in many ways weak and insecure. But as Jefferson pointed out in his inaugural address, the American nation was strong and secure because the people had found a system in which they could believe, even as they argued and fought over its execution. Jefferson said:

|

angered newly elected President John Adams. Hamilton tried to control the Adams administration from the outside and eventually contributed to the Federalist party’s loss of control of the government.

angered newly elected President John Adams. Hamilton tried to control the Adams administration from the outside and eventually contributed to the Federalist party’s loss of control of the government.  unite the nation by stressing in his inaugural address the republican values shared by members of both parties. The election of 1800 is one of the most important in our history because the transfer of power from Federalists to Republicans was achieved peacefully.

unite the nation by stressing in his inaugural address the republican values shared by members of both parties. The election of 1800 is one of the most important in our history because the transfer of power from Federalists to Republicans was achieved peacefully.