|

|

The Age of Political Machines

At the outset of the Civil War the federal government had been stretched far beyond its limits to cope with the extraordinary demands of supporting an army of over one million men. That demand ended once the war was over, but new areas of responsibility stretched the resources of government to such an extent that it could not cope with the rapid acceleration of events affecting the American society and economy. After the war the nation returned to peacetime activities—farming, manufacturing, railroad building, and all the advances stimulated by the arrival of the second Industrial Revolution. The years between the end of the Civil War and the turn-of-the-century saw huge changes in economic and social conditions, which required political attention. The realignment of politics in the decade before the Civil War and the political requirements of reconstruction, however, left the parties and Congress preoccupied with issues that had little to do with the daily affairs of working people. Although there were some notable political figures in this era, a large majority of the national leadership could be considered little more than political mediocrities: the movers and shakers were all in business, though some made good use of their financial power to buy their way into high offices such as state governorships and the United States Senate. Wealthy businessman such as Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Morgan, and others who needed to use the political process for their own ends tended to “purchase” political support rather than getting directly involved.

The dominant fact concerning the American political parties between 1875 and 1900 was that the parties were evenly divided. It was also an era in which political corruption seemed to be the norm; practices that today would be viewed as scandalous were accepted as a matter of routine. Businessmen wantonly bribed public officials at the local, state and national level, and political machines turned elections into exercises in fraud and manipulation. The narrow division between Republican and Democratic voters made both parties hesitant to take strong stands on any issue for fear of alienating blocs of voters. The result was that little got done. During this period very little serious legislation was passed; between 1875 and 1896 only five major bills made it through Congress to the president's desk. Even discussion of the graduated income tax, by any definition a revolutionary measure, failed to arouse much interest or public debate. All the same, there was wide voter participation and interest in the political process; most elections saw about an 80% turnout. Yet the unprecedented dilemmas created by industrialization, urbanization, and the huge influx of immigrants were met with passivity and confusion. Republicans. Republican presidents dominated the White House from the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 until election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. The only two Democrats elected during that interval were former Governor Grover Cleveland of New York, who was conservative enough that Republicans were more or less content with his election, and Woodrow Wilson, elected in 1912 when the Republican Party split between incumbent President William Howard Taft and Progressive candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The Republican Party held a slight edge in national politics, largely on their repeated claim that it was the Democratic Party that had caused the Civil War. Republicans were noted for waving the “Bloody Shirt,” calling Democrats responsible for the blood that was shed over secession. Starting with General Grant, Republicans nominated former Civil War officers in every election through 1900 except in 1884, again cashing in on the legacy of the war. Union veterans gravitated heavily to the Republican Party; in fact, the Grand Army of the Republic was actually an auxiliary of the GOP. Another part of the Republican base was African-American voters who tended to vote Republican—the party of Lincoln and emancipation—whenever they could. The gradual disenfranchisement of blacks in the South tended to erode the Republican base as the century progressed. Republicans were also known as the party of business, and they supported protective tariffs, transportation improvements and a tight money policy. Their philosophy, derived from the fact that the party was dominated by business, was that what was good for business was good for everyone else, including workers. Democrats. Before the Civil War the Democratic Party had become a heavily Southern party, and its strong Southern base continued until well into the 20th century. By 1900 the Democrats controlled most of the southern states, but they had difficulty electing a candidate to the White House; they could not win national office with a Confederate Civil War veteran. As mentioned above, the only Democratic president elected between 1860 and 1900 was Grover Cleveland, who was elected twice, in 1884 and 1892; he was the only American president with split terms. In the South, however, Confederate veterans had the advantage in most elections. The section was dominated by the so-called Bourbons, conservative old Southern leaders. A few anti-tariff businessmen were Democrats, along with some merchants and other business people. Democrats were just as conservative on money issues as Republicans: the politics of business was common to both parties. The northern wing of the Democratic Party leaned heavily in favor of the working classes, whose demographic makeup included Roman Catholics of German and Irish descent, white Southern Baptists, and many of the working class immigrants once they became eligible to vote. Democratic machines in the cities such as Tammany Hall in New York worked hard to get them registered and active in politics. Neither Democrats nor Republicans were willing to take strong stands on issues important to the voters. The sectionalism that had been prevalent prior to the Civil War was still alive and well, and with the evenness of political party affiliations, candidates’ personalities were important. Noted British historian James Bryce, who first visited the United States in 1870, observed firsthand the lack of action on specific issues. He wrote:

Neither the Democrats nor Republicans appealed to farmers, which led to the Granger movement, which in turn helped spawn the Populist movement, which eventually became the Populist Party. (See below.) Both political parties used machines to mobilize voters and manipulate the system. Shady tactics were openly pursued, and the charge to “vote early and often” started in this era, when political operatives sent their minions all over the cities voting in as many precincts as they could manage. In Philadelphia one ward politician boasted that, “One hundred years ago our forefathers voted for liberty in this city, and they vote here still!” The names of the signers of the Great Declaration had been placed on the voter rolls. One curious journalist noticed that a large number of voters listed the same address as their residence, and upon checking, the journalist discovered that the location was that of a house of ill repute. Political leaders did not seem particularly embarrassed by the open corruption. Republican Stalwart and machine leader Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York stated: “Parties are not built by deportment, or ladies' magazines, or gush!” To Benjamin Harrison's claim that Providence had helped him get elected, Pennsylvania Senator Matthew Quay responded, “Providence didn't have a damn thing to do with it!” (Harrison later discovered that his support had been bought by the machine: “I could not name my own cabinet. They had sold out every position in the cabinet to pay the expenses.”) Since neither side wanted to take risks for fear of upsetting the balance of power, complex issues such as the tariff and money bills moved forward slowly. The little people—farmers, laborers, small businessmen—were left out of the political equation except at the local machine level. Journalists tended to oversimplify the issues, and campaigns took on a carnival style, with much sloganeering, booze, bands, girls, and ready cash spread around liberally. At the city level, although the political machines were known for corruption and shady dealings, there was more to it than met the eye. Machine politicians actually worked very hard for their constituents; they would greet immigrants at the dockside, walk the streets in the working districts, and help poor people cut through the red tape generated by the city's bureaucracy. However, people who were awarded jobs as a result of political activity were obliged to contribute a portion of their wages to the political machines that got them their positions. Those funds, in addition to being used to bribe public officials, also went to provide direct support to those in the greatest need, a kind of ad hoc welfare system. Still, many were concerned about the level of corruption, although the time for full-blown urban reform had not yet arrived. The White House. At the national level powerful public interests tended to dominate the political landscape. All the presidents from Abraham Lincoln’s death until Teddy Roosevelt's accession where notably weak. All were more or less decent men, but none were activists. Page Smith calls them “forgettable” and characterizes them as follows:

Presidents and cabinet members were hounded by job seekers and political machine operatives seeking to collect on campaign promises made. Presidents were often, though not always, unwilling to challenge the Congress on the major issues of the day. Rutherford B. Hayes served as a major general in the Union army during the Civil War. He commanded a regiment at the Battle of Antietam in which fellow Ohioan and future president, Sergeant William McKinley, also served. Hayes served in the House of Representatives and was twice elected governor of Ohio. Although he lost the popular vote in the 1776 presidential election to Samuel Tilden of New York, he gained the White House as a result of the Compromise of 1877. Hayes was characterized by aloofness and a forbidding presence based upon his sense of moral rectitude. Mrs. Hayes became known as “Lemonade Lucy” for her refusal to allow alcohol to be served in the White House. During the great railroad strike of 1877 he was distressed and pleaded, “Can’t somebody do something for these workers?” Nevertheless, when the strikes turned violent, he called out federal troops to quell the riots, which resulted in numerous worker deaths. His actions suggested that he sided with business interests against working men, but his goal was to restore law and order, which the troops did eventually accomplish. Feeling that a return to the gold standard would help stabilize the U.S. economy, he vetoed the Bland-Allison Silver Purchase Act, but Congress overrode his veto. James A. Garfield was born in 1831, graduated from Williams College in 1856 and entered the Civil War as colonel of the 42nd Ohio Regiment. During the war he rose to the rank of brigadier general and served as Chief of Staff of the Army of the Cumberland under Major General William Rosecrans. He fought in the battles of Shiloh and Chickamauga. Elected to Congress as a Republican from Ohio in 1862, he served in the House for nine consecutive terms. Although he initially sided with the Republican Radicals, he soon became more moderate. He was elected to the Senate in 1880. When the Republican Convention of 1880 became deadlocked between former President Grant and James G. Blaine, Garfield was nominated as a dark horse candidate. In the election he defeated former Union General Winfield Scott Hancock. Garfield’s tenure as president was brief, as he was assassinated on July 2, 1881; he died on September 19. Although he did not have time to implement his plans, his inaugural address was evidence of a promising tenure in office. After reviewing the highlights of progress made by the nation since its independence, he addressed the aftermath of the Civil War. Emphasizing the meaning of the outcome of the great conflict, he said that “our people are determined to leave behind them all those bitter controversies concerning things which have been irrevocably settled” and that the “supremacy of the nation and its laws should be no longer a subject of debate.” The states’ rights debate was over, even though the states retained their “autonomy” and their right of “local self-government”; nevertheless what remained was “the permanent supremacy of the Union.” He then addressed what would be the lingering issue of racial matters long past his time in office:

Recognizing the “perhaps unavoidable” turmoil which the end of slavery had caused in the South, he affirmed that the “emancipated race … has already made remarkable progress [and] are rapidly laying the material foundations of self-support. He promised to use his authority so that all citizens would “enjoy the full and equal protection of the Constitution and the laws.” He then addressed the problem of illiteracy and the need for universal education, especially across the races. He ended his comments on the war between the states by calling for a final reconciliation of those troubling issues. He then moved on to current issues, including the volatile issue of currency reform. During his Congressional career Garfield had become perhaps the leading voice in Congress on financial matters and might well have made progress toward stability in currency by regulating the relative value of gold and silver. He addressed other economic matters and the issue of polygamy within the Mormon church, which he deplored. Finally, he spoke of the issue which would cost him his life: “The civil service can never be placed on a satisfactory basis until it is regulated by law.” Aware that he would be beset by “the inordinate pressure” of office seekers and those who supported them for political purposes, he promised action on civil service reform. The issue preoccupied him during his brief term, and, ironically, he was assassinated by a disgruntled office seeker. The tragedy of Garfield’s death is that even with the state of medical knowledge as it existed at the time, he should not have died. Recent biographer Ira Rutkow, a historian and professor of surgery, notes that even as Garfield lay dying, a medical revolution had recently taken place; uniform standards of medical education were being adopted. Garfield’s wound, though serious, was fatally undermined by lack of sanitary procedures, knowledge of which was available. Garfield’s doctors probed his wound with unsterilized instruments and fingers, ignoring the importance of antisepsis. As a result, writes Rutkow, “What had been a relatively clean bullet track was transformed into a highly contaminated one.” His painful death was the result. President Garfield suffered grievously during the two and a half months following his being wounded. Comparing Garfield’s assassination with the shooting of President Ronald Reagan’s almost 100 years later, Rutkow points out that whereas the bullet that struck president Reagan came within an inch of killing him instantly, he was “on his feet within 24 hours of the shooting and, eleven days later, returned to the White House—fully able to conduct the nation’s business.” Even absent modern medical technology, President Garfield, if treated with greater care, might have recovered with a few weeks. Had he received medical attention of the quality available when President Reagan was shot, he would likely have been back at work in his office within twenty-four hours. Vice President Chester A. Arthur had been placed on the Republican Party ticket as a concession to the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party, whose support was necessary for electoral success. Contrary to the wishes Boss Conkling, Arthur accepted the nomination and campaigned hard for the ticket. Arthur began his career as a lawyer in New York City, where he built a reputation as a supporter of civil rights by working for the integration of the New York City transportation system. Prior to the Civil War he also supported emancipation of slaves who passed through New York in search of freedom. After serving in the important position of quartermaster general of New York during the Civil War, he was appointed by President Grant to be Collector of the Port of New York. A believer in the spoils system, he appointed political cronies of Senator Conkling to the New York Customs House. President Hayes, however, removed Arthur from the office because of what he saw as corruption.

One political crony, hearing of Garfield’s death, is reported to have said, “Chet Arthur? President of the United States? Good God!” Page Smith says that Arthur surprised everyone and did a creditable job, all things considered, “thereby ensuring himself a place in history as a reformed crook.” (Smith, The Rise of Industrial America, p. 457. ) In fact, President Arthur was more than that. Upon becoming president, Arthur refused to participate in the ongoing conflict between party factions; he was determined to be his own man and to work to earn the respect of the American people whom he now served. Well aware that the assassin of his predecessor had been a frustrated office seeker, he recognized that reform in that area was necessary. Democratic Senator George Pendleton wrote the Pendleton act of 1883, the first law specifically intended to begin the professional handling of the civil service. In standing up to Roscoe Conkling, he struck a strong blow against political corruption. President Arthur pushed for passage of the act and signed it readily. The creation of the first Civil Service Commission was the beginning of the end of the spoils system. The Pendleton Act called for a merit system for promotions within the service and ensured continuity in federal employees from one administration to the next, even if the White House changed parties. In another area Arthur signed the first Federal immigration law that excluded paupers, criminals, and the mentally ill. Congress also passed a Chinese Exclusion Act that would have made Chinese immigration illegal for twenty years and restricted citizenship to Chinese. Although Arthur vetoed the bill, he signed a revised bill that was not as harsh. In foreign affairs, Arthur signed a treaty which made the United States the first Western country to establish diplomatic relations with Korea. His most significant action in the area of foreign policy was the creation of a new, steel navy as well as establishment of the Naval War College and the Office of Naval Intelligence. Those achievements made Arthur the "Father of the Steel Navy." Despite his good works in office, Arthur was not renominated in 1884. He died shortly after leaving office. His refusal to kowtow to factions in his own party earned his respect, and publisher Alexander K. McClure wrote, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected." (See whitehouse.gov) Grover Cleveland was Governor of New York at the time of his election. As has already been noted, he was said to be “a cut above the rest.” The 1884 election, however, was one of the muddiest in our history. Cleveland’s opponent, Republican candidate James G. Blaine was scorned during the campaign as “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, that continental liar from the State of Maine!” because of charges of corruption involving railroad interests. He was also suspected of anti-Roman Catholic bias. (A Republican speaker at a rally called Democrats the party of “rum, Romanism and rebellion,” referring to their positions on temperance, the Catholic Church and secession. Blaine did not distance himself from such sentiments.) The fact that Grover Cleveland had allegedly fathered an illegitimate child led to the jingle, “Ma, Ma, where’s my Paw? Gone to the White House Haw, Haw, Haw!” Cleveland’s supporters noted that the Governor had openly acknowledged the possibility of his alleged paternity and in fact had helped support the child—he directed his aides to “tell the truth.” Some Republicans united in a group known as the “Mugwumps,” reformers unhappy with the high level of corruption in government. They abandoned Blaine during the campaign and were then known as “goo-goos.” The Mugwumps claimed they would support an honest Democrat. Cleveland, the reform-minded governor of New York, met the test. With the platforms virtually identical, the election was very close; Cleveland’s margin of victory was 25,000 votes out of 10 million cast and 37 electoral votes out of 401.

During President Cleveland’s second term he distinguished himself by taking an anti-imperialist position with regard to events in Hawaii (covered in the next section.) When presented with the treaty intended to make Hawaii part of the United States, Cleveland sent investigators out to the Hawaiian Islands to see what had happened. They reported that Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani had been overthrown by an American-led insurgency, and Cleveland refused to send the treaty to the Senate. Benjamin Harrison has the distinction of being the president who served between Grover Cleveland's two separate terms, and his presidency has also been treated with a disdain accorded to the other chief executives of the Gilded Age. Yet, as is true with the other presidents who preceded and followed him, he was a decent man who tried to conduct the office according to what he believed was good for the country.

Senator Harrison supported high tariffs and pensions for Civil War veterans, and although unsuccessful in his efforts, he worked to support for education in the South, especially for the former slave population. He also opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, but his opposition, as well as his support for less favorable causes did not prevent him from getting the Republican nomination for President in 1888. Although Harrison got approximately 100,000 fewer popular votes than Cleveland, he won in the Electoral College. He was inaugurated on the centennial of George Washington’s first inauguration, March 4, 1889. Despite passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Act, Harrison still had to devote considerable time to political appointments during his term, and he appointed Theodore Roosevelt to the Civil Service Commission. He also signed a bill providing additional support for disabled Civil War veterans, and he urged Congress to advance civil rights for African-Americans. The pension act depleted some of the surplus in the treasury generated by high tariffs, but Harrison nevertheless signed the McKinley Tariff in 1890, the highest in American history. Harrison urged Congress to add reciprocity provisions to the tariff so that he could negotiate agreements on rates with other countries. He also signed the Sherman Antitrust Act, the first attempt by the federal government to control American business practices. It would be some time before it was used effectively; like the 1877 Interstate Commerce Act, however, it demonstrated that the federal government was moving into new areas and away from laissez-faire. In foreign affairs, the United States hosted the First International Conference of American States, which later became the Pan American Union, a forerunner of the Organization of American States. Harrison negotiated a resolution of the “Baltimore crisis,” which involved American sailors from the U.S.S. Baltimore who were killed in Chile during riots caused by a civil war. He also submitted a treaty recognizing a new government in Hawaii following the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani, but president Cleveland withdrew the treaty before the Senate could ratify it. (Hawaii) Benjamin Harrison nominated for a second term in 1892, but was defeated by Grover Cleveland. It is likely that the candidacy of James B. Weaver, the Populist Party candidate and former Republican, cost Harrison some votes. Weaver received more than 1,000,00 votes, a large number for a third party at that time, but Cleveland’s margin would have given him victory in any case. William McKinley of Ohio, elected in 1896 with the assistance of his manager, Senator Mark Hanna, was the last president of the Gilded Age and the last veteran of the Civil War to serve as president. His stay in the White House falls in an interesting junction in American history. In addition to serving at the turn of the century, he followed a succession of presidents who have been judged harshly by historians, and he was succeeded by one of the most dynamic presidents in American history, Theodore Roosevelt. For some reason, he has been associated more with the former than with the latter, but a recent biographer argues that although Theodore Roosevelt gets credit for being the first great progressive president, he actually built on the legacy of the president whom he succeeded. William McKinley enlisted in the Union Army as a private in 1861 and won a series of promotions for bravery and competence all the way up to the rank of major while serving under Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes. For the remainder of his life he liked to be addressed as Major McKinley, claiming, “it was the only rank I ever earned.” As a young attorney in Ohio, McKinley defended 33 striking miners, and after getting them released from jail he refused to accept any legal fees. In the election of 1876 he helped his former regimental commander get elected, and with Hayes’s help, he was elected to the House of Representatives from Ohio, where he served until 1891. During his time in Congress McKinley advanced the idea that high protective tariffs protected the jobs of American workers. As chairman of the Ways and Means committee, he authored the McKinley Tariff of 1890, the highest in history. He was elected Governor of Ohio in 1891 and served two terms. During his second term as governor he became aware that many citizens in Ohio were living in poverty. On one occasion he personally paid for a railroad car of provisions for needy miners, and he organized a statewide charity drive to raise money for food and clothing for the poor. (Charles Sumner Olcott, The Life of William McKinley, Boston, 1916, pp. 281-2 )

McKinley’s first term as president was dominated by foreign affairs, the most important of which were the Spanish-American War and the annexation of Hawaii, both of which will be covered in detail below. In domestic affairs, President McKinley pursued a conservative, pro-business agenda and signed the second highest protective tariff bill in American history, the Dingley Tariff of 1897. The only higher tariff had been the McKinley Tariff of 1890, although some rates in the Dingley Act reached 57 percent, the highest level ever. As the country recovered from the financial doldrums, McKinley’s campaign promise of prosperity seemed to be coming true. McKinley’s progressive ideas have been disguised by the fact that Theodore Roosevelt was far more rambunctious and vocal in his support of progressive causes than was McKinley. Yet in public addresses and messages during the brief months of his second term, it was clear that McKinley had laid the groundwork for many of the policies for which Theodore Roosevelt would get credit. He had already planned moving against some of the larger trusts and was no friend of the powerful senatorial Republican machine. Perhaps the most interesting measure of the harmony between the policies of McKinley and Roosevelt is the fact that virtually all of McKinley’s cabinet remained in office through much or all of Roosevelt’s two terms. That conspicuous loyalty to the man who would replace their former leader was in great contrast to the experience of previous presidents who had taken over administrations following death, whether from natural causes or assassination. Although generally relegated to the class of mediocre presidents, McKinley deserves to be among the very good at or near great presidents according to a recent biographer, Kevin Phillips. (Kevin Phillips, William McKinley, New York, 2003, pp. 156-159. ) Political Issues of the Gilded Age. The major political issues of the Gilded Age were the tariff, currency reform and civil service reform. The first two issues were of obvious interest to businessmen, and they lobbied and spent freely to gain support for favorable tariff legislation and business-friendly monetary policy. Their efforts were countered vigorously by progressive groups opposed to tight money and high tariffs that raised the cost of consumer goods. Civil service reform was a widespread reaction to the rampant political corruption of the era. Tariffs. What many Americans failed to understand was that the tariff issue is complex, as there are two kinds of tariffs with two distinctly different purposes. Ordinary revenue tariffs are modest taxes placed on imports to fund agencies responsible for goods and people entering the United States. Customs and immigration services were financed heavily by revenue tariffs. Tariffs can be specific (assessed in dollar amounts) or ad valorem (assessed as a percentage of the cargo’s value). Protective tariffs, first passed during the second James Madison administration, are quite different, and their purpose is to support American businesses and industries. Those high tariffs enable American producers to compete successfully with foreign competitors as the tariffs are passed along to consumers, thus raising the price of imported goods and making American products more attractive. Today, for example, the government places tariffs on many products such as automobiles imported from Japan and shoes imported from Italy. High tariffs were clearly not beneficial to consumers during the Gilded Age. Yet, the idea of high protective tariffs was sold to industrial workers on the grounds that if American businesses lost out to foreign competition, workers’ jobs would be threatened. On election day management representatives might warn their workers, "If you want your job to be here tomorrow, be sure to vote for the party that supports high tariffs!” High protective tariffs were the norm until the Underwood Tariff if 1913 signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson lowered tariffs significantly for the first time since 1857. Currency Reform. Another important economic issue was that of currency reform. The basic issue rests upon the premise that the amount of money in circulation determines its worth: the more money in circulation, the lower its value. Combined with that idea is the fact that paper currency not backed by gold or silver tends to lose value rapidly. During the American Revolution, for example, when the United States owned little gold or silver, the paper money in circulation was all but worthless, having a real value at times of about two cents on the dollar. For most of early American history the country’s money supply was based on a bimetallic system, that is, both gold and silver were considered specie (hard currency.) Once Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury under Washington, had brought government finances under control, the government managed to support itself through a combination of tariffs, land sales, and occasional modest duties or excise taxes. Because of the income generated from those sources, American paper soon began to retain most of its face value. The creation of the Bank of the United States and various state banks complicated the issue, for state banks had at times offered their own paper notes which circulated as “money,” but their value was unstable. They often issued more paper money than was desirable based on the amount of gold and silver they held. The Bank of the United States tended to stabilize currency, but it was a hot political issue for much of the early 19th century. It was finally disestablished during Andrew Jackson’s second term. The chief political issue regarding the money supply was whether money was “hard” or “soft.” Hard money advocates, generally bankers and operators of other financial institutions, as well as businessmen, wanted a stable currency that was not subject to inflation. Investors, speculators, and people who tended to be in debt (farmers in particular) favored a loose or soft money policy, because inflation tended to ease their financial burdens. Farmers, for example, were generally obliged to borrow money to purchase land or finance their crops, and in an inflationary environment, the prices of their crops would rise, and repayment of their loans would be easier. The financial needs of the government during the Civil War led to a variety of taxes, including the first income tax, which was enacted in August, 1861, and called for a 3% tax on incomes over $800. By 1865 the income tax produced 20% of federal receipts, but currency was still short, so the government adopted a “softer” money policy. The treasury issued $500 million in paper money not backed by gold or silver—“greenbacks.” As the fortunes of war ebbed and flowed, so did the value of the greenbacks, which occasionally sunk to as low as 35 cents on the dollar. Eventually the huge debt generated by the Civil War was converted to government bonds, which were paid off over time, and the greenbacks were gradually taken out of circulation. The Fourth Coinage Act of 1873, called the “Crime of ‘73” by soft-money advocates, made gold the sole monetary standard, even though large quantities of silver were being produced by western mines. The resultant tightening the money supply brought deflation of currency, which aroused anger among people who benefited from inflationary policies. Currency reform thus became a hot political issue for several decades. For years many believed that a "gold conspiracy" was behind the issue and that politicians were beholden to those interests.

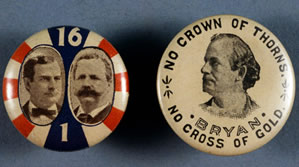

While the discontinuation of silver coinage foreclosed an important method of expanding the currency supply, the actual supply of silver increased. As demand dropped, the price of silver fell, contributing to the deflationary cycle. Thus the silverites gained support from farmers, debtors, and speculators who wanted larger money supply; they demanded “Free Silver,” i.e., unlimited coinage of silver, which would be inflationary. The admission of six new western states under President Harrison in 1889 and 1890 led to increased Congressional pressure in support of silver, and in 1890 the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was passed. The act required the treasury to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver per month to be converted into coins and silver certificates (paper money backed by and redeemable as silver.) The $500 bill pictured would have been redeemable in gold. The issue persisted, coming into sharp focus during the 1896 Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago in July. William Jennings Bryan, a populist Democrat from Nebraska, gave a speech which became known as his “Cross of Gold Speech.” It was said that the speech, which repudiated the policies of the Cleveland administration, led to his nomination on the fifth ballot. In that famous oration he said of the gold backers:

Thus William Jennings Bryan became the Democratic candidate for president in 1896. He was also nominated as presidential candidate by the Populist Party, and their decision to back a Democrat ended their effectiveness as a third party. Despite that support, Republican William McKinley won the 1896 election, and pro-business forces remained in control until the accession of Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who furthered the cause of progressives when he took office in 1901. Civil Service Reform. President Andrew Jackson had argued that the “spoils system”—the awarding of government positions to loyal political supporters—actually enhanced the democratic process; Jackson believed that any average, intelligent citizen was able to perform the mundane tasks of government clerks and officials. As political machines gained more control over partisan activities, however, the awarding of government jobs was increasingly seen as a source of corruption. Thus the movement for civil service reform was fueled to some extent by a desire to reduce political corruption. In addition, as society grew more complex during the industrial, the ability to perform routine tasks under government employment also became increasingly complex. It was apparent for these reasons that a professional civil service was required, with employees who would no longer be subject to the political winds. As mentioned earlier, President Hayes's advocacy of civil service reform put him on a collision course with Congressional bosses. He removed Chester Arthur and Alonzo Cornell from the New York City Customs House for failure to carry out reforms. Both were underlings of New York Senator and Republican political boss Roscoe Conkling, who thought it an attack on him or his machine. Conkling invoked senatorial privilege and got the Senate to withhold consent for replacements for months. President Hayes stuck to his guns, however, and eventually got enough Democratic support to get his appointees approved. When President James A. Garfield was assassinated four months after assuming office, people were shocked to discover that the assassin was a disgruntled office seeker who had been trying to get a position in Garfield’s administration. Garfield had showed great promise before his assassination, and support for civil service reform grew significantly. The reason behind the assassination attempt, along with evidence of fraud in government, especially in the Bureau of Indian Affairs and in railroad supervision, led to the founding of the National Civil Service Reform League in 1881. The result of the reform agitation was passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act in 1883, signed by President Arthur. The act in effect ended the spoils system by classifying certain jobs, which meant they could not be awarded on the basis of patronage. In addition the United States Civil Service Commission was established to construct a system under which people would be hired on merit rather than on the basis of political connections. By 1900 about half of all federal employees were classified, and today virtually all regular civil servants, with the exception of high level policy appointees, are controlled by the civil service system. Regulating Commerce and Business. In the year 1800 it would scarcely have occurred to founding fathers such as Jefferson, Hamilton, or Madison, to consider that the role of the government was to regulate business. The Constitution, however, assigned responsibility for controlling interstate commerce to the United States Congress. In the case of Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824, Chief Justice John Marshall affirmed that concept when he declared that the federal government had the exclusive right to control commercial transactions between the states. (The case invalidated a New York State law that had granted monopoly privileges to a ferry operating between New York and New Jersey. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution states: The Congress shall have Power … To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States.) The accepted approach to the relationship between government and business for most of American history had been that of laissez-faire,—letting business operate more or less unimpeded by government. People believed government interference with business could have no beneficial effects. Yet as the power of corporations grew, along with their size and numbers of employees, and as sharp competitive business practices rendered the playing field uneven, it became clear that a problem existed. Corporations, especially large ones operated by the so-called robber barons, were responsible for significant amounts of hardship in people's lives. During the last half of the 19th century it became apparent that large businesses needed to be regulated. As a result, the tradition of laissez-faire was not only impractical but actually dangerous. Business-labor relations often degenerated into bloody contests fought to the death between business managers and the workers who served them. The inevitable result was that the government had to assume the burden of regulating the workplace. It was the interface between government and the American economy that dominated the political life of the Gilded Age, a nexus that in large measure has continued ever since that time. Social Darwinism. Working in favor of continuing the laissez-faire approach was the concept of Social Darwinism. Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, was a controversial work. Its impact soon reached beyond the subject of biological evolution (which had put it at odds with many fundamentalist religious beliefs), and it moved into the social arena. The idea of survival of the fittest, an offshoot of Darwin's original thesis, was applied to the human environment. The idea was to let people wade in to the morass of life and either get stuck or crawl out under their own power. Survival of the fittest thus became the social (and international) byword. When combined with Adam Smith's idea of allowing the market to determine success and failure in the business world, it meant that businesses were expected to do whatever was necessary to survive. Only by defeating their competitors could they hope to prosper. Business practice became ruthless and cutthroat; survival went not only to the fittest, but also to the wiliest, the most crooked, and the most corrupt organizations. Something had to be done. Businesses quickly realized that in order to continue to operate in the laissez-faire environment that had persisted from revolutionary days they would have to fend off attempts by government to become more involved in economic policies. Since businesses required political support, and since politics required healthy injections of money, business-political alliances were forged. Such coalitions did not always serve the public well. Railroads, for example, offered free passage to Congressmen, other government officials and their friends. They even went so far as to give them complimentary shares of stock in building corporations for railroad expansion. When John D. Rockefeller was developing Standard Oil, it was said that he “did everything with the Pennsylvania legislature except refine it.” Practices of that sort, which would today violate Government ethics many times over, were considered a normal part of doing business during the Gilded Age. In particular, people who depended on railways for business purposes were hurt by the fact that, at least on the local level, railroads had a monopoly on transportation of goods from producer to market. Shipping rates were uneven and often unfair, especially on lines where no competing systems were available. In addition, large corporations such as Carnegie Steel or Standard Oil were able to pressure rail companies to give them favorable rates and rebates (refunds under the table). On top of those special rates, they also forced shippers to pay drawbacks—payments for goods shipped by the giant companies’ competitors. They pulled no punches in defeating competition through discriminatory rates. Farmers in particular were subject to the will of the railroad operators, especially when the roads owned and operated grain silos and other storage facilities, which farmers had no choice but to use. The Interstate Commerce Act As a result of those questionable practices, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act in 1877. The Act stated:

It further declared that rebates, drawbacks and other under-the-table payments were illegal. Although the Act had to be strengthened by subsequent legislation, the Interstate Commerce Act was the first step in bringing transportation facilities under government oversight. The Sherman Antitrust Act. The first major break with the concept of laissez-faire came with the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act. Businesses were prohibited from using monopolistic practices or acting in restraint of trade and taking unfair advantage of competitors. Like the Interstate Commerce Act, the Sherman Act had to be modified and tightened by later legislation, but the mere passage of the act demonstrated that the age of unbridled corporate excess was coming to an end. Major sections of the Sherman Act were:

AGRICULTURAL DISCONTENT & THE POPULIST MOVEMENT The Populist movement began in the late 19th century, and its roots lay in the discontent of farmers. As settlers moved from farms in the East with their lush, green settings, where neighbors were within hailing distance of each other, out onto the Great Plains, they had to make substantial changes. They had to learn new kinds of farming, as annual rainfall was much lower than in the East. The soil was often hard and unyielding, and they had to learn what was known as “dry farming.” Because they needed to grow crops such as wheat and corn in large quantities, the size of farms was larger than the East, and the distances between farms was substantial. Farming life on the Great Plains was thus a lonely existence. Women in particular, sometimes isolated from all but their family for weeks at a time, often suffered from depression brought on by the lack of human contact. It was said on the Great Plains, where the wind blows freely and often unceasingly, that women were often driven mad by the wind. (In the musical play Paint Your Wagon, about homesteading in the West, there is a song “They Call the Wind Mariah.” One line goes, “Mariah makes the mountains sound like folks was up there dyin’.”) Men, of course, were not immune to the challenges of frontier life, and strong women often carried on when husbands or fathers were defeated by the harsh environment. (Willa Cather’s well-known novel, O Pioneers, (1913) movingly depicts frontier life in Nebraska.) To combat their isolation farmers began to organize into social groups. They would go into the towns on Saturday night and enjoy hot meals, music, dancing and conversation. That conversation often turned to sharing their troubles, such as being beholden to railroads for transporting their goods and renting out the silos and storage facilities where grain was loaded before being shipped. Farmers were chronically in debt—they had to invest in supplies, machinery and labor before their crops were harvested and sold, and thus often had to borrow money to stay in operation. Farmers were therefore economically hampered by the interest rates they had to pay on loans. Many were deeply indebted to mortgage companies. To make their troubles worse, as farmers got better and better at their jobs, with more efficient farming methods and equipment, they drastically increased the supply of agricultural goods they were producing, including grains, livestock, and other commodities. Furthermore, with increased, faster transportation both on land and on sea, they began to face competition from other parts of the world. Argentinean beef farmers, for example, competed with American beef producers. The increased supply of farm products drove prices ever lower, to the point where farmers found themselves trapped between rising costs and falling prices. As was discussed above in the section on currency, an additional hardship came from the fact that the tightness of currency tended to cause prices of farms products to remain stable or even decline. (It is a myth is that inflation hurts everybody; people who have fixed debt find that inflation, which brings rising prices, helps them pay off their loans faster.) The actual amount of money in circulation per capita was decreasing during this period. Conservative money interests wanted to retain the gold standard and limit the supply of silver currency, while soft-money advocates wanted not only more silver coins but even greenbacks—paper money with no specie backing—to be circulated. All these factors, along with discriminatory railroad rates, unfavorable marketing arrangements, and high protective tariffs, were the constant subject of conversations among farmers. High tariffs raised in particular the costs of farm equipment needed by farmers. Their discontent led to the creation of the Granger movement, the “Patrons of Husbandry,” a secret organization designed to promote the interests of farmers. Having begun as a social movement to counter the lonely, hard life of the farmer and his family, the Grangers soon turned to political action. Part of their activities were of the self-help variety. They shared information on farming through education, used cooperative ventures to purchase silos and machinery, and brought pressure on groups they saw as their oppressors, namely railroads and banks. But they sought political solutions as well. The Grangers were aided by others who faced many of the same problems, such as small businessmen and merchants. They began to sponsor legislation and got laws passed at the local and state level in the 1870s and 80s. Eventually, around 1890 these somewhat diverse groups congealed into a national political party, the People's Party or Populists. Recognizing that they needed help from the federal government, which had the constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce, they entered big-time politics. The Populists were not outright Socialists, but many of their goals resembled those of the European socialist parties which were flourishing at the same time. The Populists’ goals included more equitable distribution of wealth, and a humanistic social system. The Populists had what was referred to as a “millennial outlook"—a Utopian view of the future—and they were often strongly religious people. Populist reformers wanted to be “governed by good men.” Many conservative interests saw the Populists as a threat to the basic economic system of the United States, but the free market economy had always worked against the farmer. If the free market functions on the laws of supply and demand, and supply vastly outstrips demand, the results are likely to be disastrous for the suppliers; in fact, that condition has been the lot of American farmers for much of our modern history. (In 1922 the price of a loaf of bread compared with other commodities was the lowest it had been in 500 years.) Despite their successes, however, the Populists had trouble building a national party. They were perhaps too radical for the time, and many of their ideas seemed somewhat akin to the Communist and Socialist parties of Europe. Ultimately the Populist Party failed to survive. They did well in 1892, but they lacked the money, organization and candidates to follow through in 1894. In that year their total vote was up 50%, but they made few electoral gains. Fusion with the Democratic Party seemed to be the only answer, but many Populists didn’t agree with that approach. In 1896 however they endorsed the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan for president, and thus virtually gave up their party identity. (Bryan's Cross of Gold speech gives considerable insight into why the Populists found him so appealing.) In the early 21st Century there are no viable third parties in United States; although the Libertarian and Green Parties generally manage to field candidates for president, they seldom achieve significant vote totals and thus rarely have an impact on election outcomes. The two major parties are divided roughly evenly as recent elections have shown. Much of the present political rancor comes from dissatisfied citizens over specific issues; there is, however, no third party through which people can vent their grievances. Summary: By the 1890s the nation is approaching a state of crisis. With increases in industrialization, the workplace is becoming ever more dangerous, and businesses refuse to accept responsibility for injuries to workers. As farmers become more efficient in producing crops, supplies tend to outstrip demand regularly, thus depressing prices. From time to time farm production is severely impeded by droughts, storms, infestations of locusts and other parasites, and it becomes increasingly challenging for farmers to make economic progress. In the mid-1890s a serious depression makes things worse, and the Populist rebellion grows in strength. Historian H. W. Brands characterized the 1890s as The Reckless Decade in his book with that title. The Gilded Age was a time of enormous progress for the country. Production expanded in unimaginable proportions, living standards rose dramatically as thousands of white collar, middle-management jobs were created. Great fortunes were amassed, millions of immigrants found hope on America's shores. Furthermore, technology began to supplant human muscle power with machine power, with huge increases in productivity. But all that progress had a price. As reformer Henry George pointed out, the side by side existence of massive progress with appalling poverty is the great paradox of the age. Labor was nearly crushed, and a massive workers' rebellion might have occurred with no-one-knows-what results. Reform was essential, and it came in the form of the Progressive Movement.

|

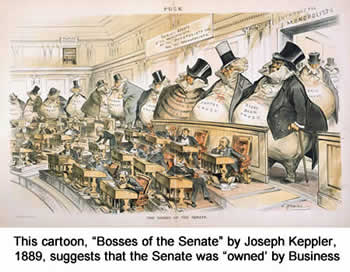

During the Gilded Age, 1876-1900, Congress was known for being rowdy and inefficient. It was not unusual to find that a quorum could not be achieved because too many members were drunk or otherwise preoccupied with extra-governmental affairs. The halls of Congress were filled with tobacco smoke, and spittoons were everywhere. One disgusted observer noted that not only did the members chew and spit incessantly, but their aim was bad. The atmosphere on the floor was described as an “infernal din.” The Senate, whose seats were often auctioned off to the highest bidder, was known as a “rich man's club,” where political favors were traded like horses, and the needs of the people in the working classes lay beyond the vision of those exalted legislators. The Senate dominated the federal government during the Gilded Age, often calling the tune to which presidents were required to dance.

During the Gilded Age, 1876-1900, Congress was known for being rowdy and inefficient. It was not unusual to find that a quorum could not be achieved because too many members were drunk or otherwise preoccupied with extra-governmental affairs. The halls of Congress were filled with tobacco smoke, and spittoons were everywhere. One disgusted observer noted that not only did the members chew and spit incessantly, but their aim was bad. The atmosphere on the floor was described as an “infernal din.” The Senate, whose seats were often auctioned off to the highest bidder, was known as a “rich man's club,” where political favors were traded like horses, and the needs of the people in the working classes lay beyond the vision of those exalted legislators. The Senate dominated the federal government during the Gilded Age, often calling the tune to which presidents were required to dance. Hayes announced early that he would not run for reelection, which might have made him a lame duck from the start, but his moral convictions led him to fight against the corruption that had been apparent during the Grant years. He took on the powerful Republican Party boss of New York, Senator Roscoe Conkling, and fired the latter’s chosen head of the New York Customs House, Chester A. Arthur, thus helping to pave the way for civil service reform. Hayes also signed an executive order prohibiting federal office holders from participating in political party activities and suspended political contributions to office holders.

Hayes announced early that he would not run for reelection, which might have made him a lame duck from the start, but his moral convictions led him to fight against the corruption that had been apparent during the Grant years. He took on the powerful Republican Party boss of New York, Senator Roscoe Conkling, and fired the latter’s chosen head of the New York Customs House, Chester A. Arthur, thus helping to pave the way for civil service reform. Hayes also signed an executive order prohibiting federal office holders from participating in political party activities and suspended political contributions to office holders.  After Garfield’s election, Conkling began making demands of the incoming president as to appointments, and Arthur supported his longtime patron against his new boss. The bitterness between the Republican factions was so sharp that President Garfield and Vice President Arthur had practically no contact right up until Garfield’s death. The patronage issue boiled up as Garfield’s assassin, upon shooting the president, shouted, “I am a Stalwart … Arthur is President now!" Thus Arthur’s term as president began in controversy.

After Garfield’s election, Conkling began making demands of the incoming president as to appointments, and Arthur supported his longtime patron against his new boss. The bitterness between the Republican factions was so sharp that President Garfield and Vice President Arthur had practically no contact right up until Garfield’s death. The patronage issue boiled up as Garfield’s assassin, upon shooting the president, shouted, “I am a Stalwart … Arthur is President now!" Thus Arthur’s term as president began in controversy.  President Cleveland, whose administrations were split into two separate terms, was a rigid, self-righteous, haughty individual and thus did not inspire affection. However, he was honest, courageous, and possessed integrity. He had fought the New York City Tammany Hall machine and had become famous as the “veto mayor” of Buffalo and later the “veto governor” of New York State. His stalwartness was both a blessing and a shortcoming once he was in office. People said of him, “We love him for the enemies he has made.”

President Cleveland, whose administrations were split into two separate terms, was a rigid, self-righteous, haughty individual and thus did not inspire affection. However, he was honest, courageous, and possessed integrity. He had fought the New York City Tammany Hall machine and had become famous as the “veto mayor” of Buffalo and later the “veto governor” of New York State. His stalwartness was both a blessing and a shortcoming once he was in office. People said of him, “We love him for the enemies he has made.” Like all Republican presidents who served between the Civil War in 1900, he participated in the Civil War, starting as the colonel of the 70th Indiana Regiment and rising to the rank of brigadier general, the rank he held while commanding a brigade during Sherman’s Atlanta campaign. A Whig during his the years before the Civil War, Harrison remained active in politics in the postwar years. He sought the governorship of Indiana twice, both times unsuccessfully, but was elected to the United States Senate from Indiana where he served from 1881 to 1887.

Like all Republican presidents who served between the Civil War in 1900, he participated in the Civil War, starting as the colonel of the 70th Indiana Regiment and rising to the rank of brigadier general, the rank he held while commanding a brigade during Sherman’s Atlanta campaign. A Whig during his the years before the Civil War, Harrison remained active in politics in the postwar years. He sought the governorship of Indiana twice, both times unsuccessfully, but was elected to the United States Senate from Indiana where he served from 1881 to 1887. Fellow Ohioan Mark Hanna, former businessman, Senator, and chair of the Republican National committee, saw William McKinley as a likely candidate for the highest office and sponsored his friend for president in 1896. In a highly organized campaign, McKinley defeated William Jennings Bryan, whose advocacy of free silver was his only issue. Many had blamed Grover Cleveland for the economic downturn following the panic of 1893, and McKinley was swept into office by a comfortable margin.

Fellow Ohioan Mark Hanna, former businessman, Senator, and chair of the Republican National committee, saw William McKinley as a likely candidate for the highest office and sponsored his friend for president in 1896. In a highly organized campaign, McKinley defeated William Jennings Bryan, whose advocacy of free silver was his only issue. Many had blamed Grover Cleveland for the economic downturn following the panic of 1893, and McKinley was swept into office by a comfortable margin. The controversy between “silverites” and “gold bugs” continued and was one of the key issues that led to creation of the Populist Party. Farmers in particular were hurt by tight money policies and demanded reform. However, both major parties tended to favor tight or hard money. The formation of the Greenback Labor Party in 1874, which advocated a return to paper money, provided little relief, and the issue would remain contentious for another quarter of a century.

The controversy between “silverites” and “gold bugs” continued and was one of the key issues that led to creation of the Populist Party. Farmers in particular were hurt by tight money policies and demanded reform. However, both major parties tended to favor tight or hard money. The formation of the Greenback Labor Party in 1874, which advocated a return to paper money, provided little relief, and the issue would remain contentious for another quarter of a century.  The Populists were an enthusiastic lot, and it was said that the atmosphere of Populism was like that of a revival meeting, probably including many shouts of “Hallelujah” and “Amen!”

The Populists were an enthusiastic lot, and it was said that the atmosphere of Populism was like that of a revival meeting, probably including many shouts of “Hallelujah” and “Amen!”