A Decade of Turmoil

This portion of the site begins with the Roaring Twenties, a decade that stands apart as a sort of dividing line between the 19th and 20th centuries. We divide history into nice round numbers: centuries, decades, and even millennia. But time periods don’t always break at those logical points. For example, the events surrounding the French Revolution and Empire, including the Napoleonic wars, seem to belong more with the 18th century than with the 19th. Thus it is probably fair to say that in a real sense the historical epoch called the 18th century actually ended in 1815 with Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic era. We also look at the period from 1815 to 1914 as the “Hundred Years’ Peace” to distinguish it from other epochs.

The decade of the 1920s saw substantial changes in domestic American life as Victorian society was replaced by the age of the flapper. At the end of that raucous decade, the crash of the stock market helped trigger the worst depression in America's history, and as the United States struggled to regain her economic footing, she went through a period of self-imposed detachment from the affairs of the rest of the world. Much of the world was in turmoil, politically as well as economically, and although Presidents Harding, Coolidge, Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt kept an eye on foreign affairs, their focus was generally on domestic issues, at least until the late 1930s.

Likewise, the end of the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles can be seen as the culmination of the imperialist drive that was part of the late 19th century. Thus it is not too far amiss to say that in a sense the 19th century ended at Versailles; many of the developments we associate with the 20th century did not really begin until 1920.

This method of sorting out different eras is not consistent, nor should we try to make it so. For example, it is probably fair to say that the Progressive Era is more of a 20th-century phenomenon than a 19th century event. When we look back on the 20th century we may say that a major, epochal turning point was the end of the Cold War. On the other hand, the events of September 11, 2001, ushered us in to a new era that is likely to dominate much of the 21st century.

Just as the 1890s were a reckless decade and a precursor of things to come, the 1920s were also a wild and woolly period, when old values seem to be cast aside and new ideas bubbled up in many areas of American life. The decade of the 1930s is also a separate era, in that the Depression of that decade was one of the worst in American history and certainly stands alone in its duration. On the other hand, the isolationism of the 1930s harkens back to some extent to American isolationism of much of the 19th century.

The point here is not to draw lines or declare beginning and end times. The point is that our history has twists and turns, beginnings and endings, and often history does repeat itself in fascinating and sometimes troublesome ways. In any case this third section of the book covers an era that changed the world in ways that would hardly have been imaginable at the dawn of the 20th century, or even as the decade of the 1920s began.

A Decade of Change

The “Roaring Twenties” was a decade in which nothing big happened—there were no major catastrophes or large events—at least until the stock market crash of 1929—yet it is one of the most significant decades in U.S. history because of the great changes that came about in American society. The Twenties were known by various images and names: the Jazz Age, the age of the Lost Generation, flaming youth, flappers, radio and movies, bathtub gin, the speakeasy, organized crime, confession magazines, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Charles Lindbergh, Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, the Great Crash, Sacco and Vanzetti, Al Smith, cosmetics, Freud, the “new” woman, the Harlem Renaissance, consumerism—all these images and more are part of the fabulous Twenties!

The 1920s provided something of a roller coaster ride for the American people. The euphoria surrounding the end of World War I was clouded by the great flu epidemic of 1919, the Red Scare of that year, and the frustration and bitterness left over from the fight over the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. The progress made toward reform under progressive Presidents Roosevelt and Wilson slowed to a crawl, as many Americans began to feel the need for a break from the moral intensity of the Progressive Era.

Demobilization from World War I proceeded more or less haphazardly. Thousands of troops were discharged as the army was reduced to its prewar size. The shipbuilding program was halted, and naval cargo vessels were sold to private shipping firms. Railroads were returned to private control, although the ICC was strengthened to make them both more responsive to people’s needs and more efficient. A period of labor strikes and race riots was followed by a business recession early in the decade. Recovery resumed in a pro-business environment under three successive Republican administrations, and consumerism reached new heights as the age of advertising and credit buying advanced full bore.

Cultural conflicts and reactionary attitudes toward immigrants revealed deep differences among different segments of the population. A golden age of radio, film, and sports was offset by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and struggles to make Prohibition work. In the latter part of the decade the stock market began to soar to unheard-of heights, and speculators pumped more and more cash, much of it borrowed, into increasingly inflated stocks. When the inevitable crash came, reverberations were felt around the world, and the country was soon plunged into its worst depression in history.

Though the Twenties was a decade of enormous social change, myths about the era sometimes exaggerate the reality of that strange and often troubling time. While consumerism boomed and many new inventions—radios and telephones, for example—became everyday items for many Americans, it was also a time of much bitterness, conflict, and disappointment. The economic boom left many in the dust, America’s traditional openness to immigration was severely cut back, and racial tensions rose. Prohibition, the “noble experiment,” caused ordinary citizens to resort to criminal behavior, even as government often winked and looked the other way.

Following the Great War, as the only major Western nation not devastated by that conflict, Americans felt pretty good about themselves. The continued economic growth, political conservatism, and general absence of concerns over foreign affairs led Americans to think of themselves as “having it made.” Proof of America’s spirit and achievements seemed to be personified by Charles Lindbergh as he made his historic flight from New York to Paris in 1927. But the 1920s also saw deep divisions in the country despite the “roaring” atmosphere brought about by bathtub gin, speakeasies, flappers, women voting, jazz, sports, and all the rest. Then at the end of that self-satisfied, raucous, and somewhat grumpy decade, when the expectations of many Americans knew no bounds, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression hit.

The Twenties were also known as a time of revolution in manners and morals, when young men, and especially young women, threw off many of the social restrictions of the Victorian era and began conducting themselves in ways that scandalized the older generations. Young women liberated themselves in everything from hairstyles and clothing to deportment and public behavior, smoking cigarettes and drinking from flasks of illegal bootleg whiskey and bathtub gin. The ’20s were known as the jazz age and saw the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, divisions between town and country that went beyond mere style, the Harlem Renaissance, an enormous growth in production of items such as automobiles once seen as luxuries, and a general feeling of near euphoria, as if for the middle and wealthy classes, at least, things would just keep going up.

The stock market crash of 1929 ended the dreams of many and ushered in the Great Depression of the 1930s. Although the crash was not the cause of the Depression, it had a triggering effect, and the underlying economic weaknesses in the American economy brought on a period that was devastating for millions of Americans. The Twenties saw Lindbergh fly solo across the Atlantic and Babe Ruth hit sixty home runs. But it also saw the Scopes trial and the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti following their famous murder trial. It was a time of revolution, and as Dickens said of an earlier revolution, in many ways it was the best of times and the worst of times.

The decade began amidst the ashes of the Great War, then part of the legacy of that conflict was the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 and 1919, brought to the United States by soldiers returning from Europe. The toll was staggering as 22 million people died around the world from the strange disease. From September 1918 through June 1919, 675,000 Americans died from flu and pneumonia. People began wearing surgical masks in public places, and venues in which people came in close contact, even including churches, were closed in an attempt to prevent further spread of the virus.

Recovering from World War. As it had done after every war it ever fought, the United States disarmed rapidly after World War I.

- Naval cargo vessels were sold off, millions of men were discharged and the Army was reduced to about 100,000 soldiers. The services did their best with what they had and began looking ahead to the next war, often very perceptively.

- In 1920 the railroads were returned to private control, but the I.C.C. was strengthened to make them both more responsive to people’s needs and more efficient.) A Railroad Labor Board was established for labor disputes.

- Businesses set out to meet the demands of consumers, producing household appliances, automobiles and other goods on record-breaking quantities. The strong government control of business during the war had set a precedent for further involvement later, and made control of businesses after war easier to sustain.

- Government very tough on labor during the 1920s—public opinion supported that course. Legislation supports open shops; union membership 5.1 million in 1920, 3.6 million in 1929.

The Red Scare of 1919. Americans knew about Communism, because Communists had been at large in the country for years, often associated with radical labor organizations such as the IWW, and Communist Party meetings were held in New York and other major cities more or less openly. (See Warren Beatty’s film Reds for an interesting story about the radical politics of that era.) Americans accepted and wanted to preserve the American way of doing things, which meant capitalism, private ownership of business, free-market competition, and the Horatio Alger myth that with enough pluck and a little luck, anyone could become a millionaire.

When the Bolshevik revolution succeeded in Russia, however, it sent a shock wave through the western world, and it was felt in America. Americans have never been sympathetic to radicalism in any form, and this case was no different, especially when rumors of a Communist-inspired “world revolution” were heard. Some radical activity clearly justified a response, as when a bomb was placed on the front door of the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. (It exploded prematurely, killing the bomber and frightening the children of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, who lived across the street.) As additional bombs were found in the mails, the problem was blamed on “Reds,” and the government responded.

Under the direction of Attorney General Palmer, the FBI in 1919 set about rounding up “undesirables,” many of whom were innocent persons, and deported hundreds from the country. Others associated with radicalism, rightly or wrongly, were harassed, lynched, jailed, and were subjected to all sorts of bigotry. Thousands were arrested in 1919 and 1920 and often held for long periods without trial. The “Red Scare” lasted only about two years, but it showed how frightening it could be to be the “wrong sort of person” in America at that time. Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian immigrants, felt the sting of the anti-anarchist feelings when they were executed in the electric chair in 1927. The Red Scare of 1919–1920 was a precursor of McCarthyism, the anti-Communist witch hunt led by the Wisconsin Senator during the 1950s.

The Twenties were also a time of reaction against war—the Great War in particular and war in general—for although the Americans suffered relatively few casualties in 1918, they came during a very short period of time—more than 100,000 men died from all causes in about six months of actual fighting. From that disillusionment the Twenties also brought a reaction against the expansionist ideas that had gotten America an empire and embroiled her in the Great War. The widely held myth that human progress was advancing was exploded in the trenches of Europe’s battlefields.

The Twenties were in another sense a reactionary decade—a reaction against Victorian ideas of morality that saw young men and women openly defy what their parents still viewed as proper behavior for relationships between the sexes. Young people went wild, in the eyes of some, though studies have suggested that there was more talk than action. It was also a rebellious age, in which women continued the process of breaking out of older social patterns as they had begun to do during World War I. They changed their dress styles, cut their hair short, smoked in public, and were not above taking a nip from a flask of Prohibition whiskey.

Films tended to reinforce the changing patterns, as vamps such as Theda Bara starred in films the were soon considered scandalous, and the movie industry began placing restrictions on what could be shown. But the sexual openness also advanced the notion of romantic love, and women began to be seen more as partners in marriage than objects. That phenomenon led to changes in family relationships, as birth rates fell and young people had more freedom, provided in part by the automobile, but also by shifting cultural practices. Writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway caught the mood of the time in novels such as This Side of Paradise, The Great Gatsby,and The Sun Also Rises.

Women were also more liberated politically, as they gained the right to vote with ratification of the 19th Amendment on August 21, 1920, but as was said in a famous play of the time, they could no longer hide behind the petticoat. Liberation brought increased responsibility, and it was only partial in any case. People talked more openly of sex, but anti-obscenity laws still made it difficult to get information about birth control. Women found it easier to find jobs, and working outside the home was more acceptable, but women rarely became doctors, lawyers, or business managers. Initially women voters changed the political landscape very little, as most tended to vote with their husbands or other male family members. The League of Women Voters was formed to assist women who wanted to learn more about politics. The first Equal Rights Amendment was introduced in Congress in 1923 but got nowhere. Women had come a long way, but still had a long way to go.

Town and Country Conflicts

Because of the growth of cities brought by immigration and internal migration, a sharpening divide grew between urban and rural areas. Sophisticated city dwellers began to look at their country cousins as hicks or bumpkins, whereas those in the farm belts viewed the cities as places of degradation, immorality, and “foreign” influences. For example, Prohibition was probably followed more in what was called the “Bible Belt” than in New York and Chicago, although moonshining prospered in the rural woods.

Prohibition. The prohibition of the sale or use of alcohol for other than religious or medicinal purposes has been called a “noble experiment.” If indeed it was, it was an experiment that failed to achieve its main goal. It did manage some partial victories: deaths from alcohol-related diseases did go down. Accidents from alcohol abuse were lessened in some areas, and thousands of people did stop drinking, with likely benefits to the health and sanity of those who might otherwise have become alcoholics. On the other hand, many thousands continued to drink in defiance of the law, and the enormous sums that could be earned from the illegal production, importation, and distribution of wine, whiskey, and beer financed organized crime throughout the period of Prohibition. Al Capone’s income from his mob activities was estimated at $60 million per year.

(See the film The Untouchables with Kevin Kostner about breaking the Al Capone Ring in Chicago. Though not very accurate historically, the film does depict the problems faced by those attempting to enforce Prohibition.)

Although more than thirty states had gone dry before Prohibition, and many jurisdictions stayed all or partially dry after Prohibition ended in 1933, many have claimed that Prohibition overall did more harm than good. In any case the Prohibition experiment provides some historical insight into our current drug-related problems. The struggle over Prohibition also tended to drive city and country even farther apart.

Prohibition Resources: (Thanks to Sophie Price for pointing out these links.)

- Prohibition History: Mob Museum

- Prohibition Unintended Consequences from PBS

- A Digital History of Prohibition

- Why Prohibition was a Failure: Cato Institute

- Library of Congress Site on Prohibition

Fundamentalism. Much of the difference between town and country was rooted in religion, as many in rural areas gravitated toward various brands of religious fundamentalism. Fundamentalists insisted that the book of Genesis was the actual story of creation, and that theories such as Darwin’s evolution were the work of the devil. This conflict was dramatized by one of the most famous trials of the century—the Scopes or “Monkey” trial in Tennessee in 1925.

The state of Tennessee had passed a law making the teaching of evolution in schools illegal, although when the governor signed the law, he expected and hoped that it would never be used. Encouraged by citizens of the small town of Dayton, Tennessee, however, and with the backing of the ACLU, high school teacher John Scopes was persuaded to schedule classes on evolution in violation of the law. The citizens of Dayton had sought publicity, and they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. Although the conviction of John Scopes was a foregone conclusion (no one denied that he had been willing to teach evolution), the trial turned into a showcase for the issue of academic freedom versus Orthodox Christianity.

The Scopes Trial. Attracted by the presence of three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, who came to support the prosecution, as well as famous agnostic lawyer Clarence Darrow of Chicago, who came to defend John Scopes, the media and the curious descended upon the town. Among those was Baltimore journalist H. L. Mencken, whose newspaper offered to pay the $100 fine that John Scopes was awarded upon conviction. Prevented by the judge, who was obviously biased in favor of the prosecution, from presenting any scientific witnesses, Darrow finally decided to put William Jennings Bryan on the witness stand as an expert witness on the Bible.

The Scopes Trial. Attracted by the presence of three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, who came to support the prosecution, as well as famous agnostic lawyer Clarence Darrow of Chicago, who came to defend John Scopes, the media and the curious descended upon the town. Among those was Baltimore journalist H. L. Mencken, whose newspaper offered to pay the $100 fine that John Scopes was awarded upon conviction. Prevented by the judge, who was obviously biased in favor of the prosecution, from presenting any scientific witnesses, Darrow finally decided to put William Jennings Bryan on the witness stand as an expert witness on the Bible.

Darrow’s examination of Bryan demonstrated that matters of faith can be difficult to prove in a court of law. Insisting upon a literal interpretation of the Bible, Bryan was obliged to defend the supposed date of the creation of Earth (around 4000 BC), Jonah being swallowed by a big fish, Joshua’s commanding the sun to stand still and Cain’s taking of a wife, even though the only woman created so far according to the Bible had been Eve. The heat of the exchange often matched the sweltering temperature in the courtroom, and at least partially as a result of the strain of the confrontation, Bryan died shortly after the trial. Scopes’s conviction was overturned on a technicality, but the trial brought the issue of religious controversy to the front pages all over America.

See the film Inherit the Wind, the 1960 version with Spencer Tracy as Colonel Drummond (Clarence Darrow) and Frederic March as Matthew Harrison Brady (William Jennings Bryan), for a sense of what that event was like. Dramatic themes and details have been added, but the essence of it is sound history, based on the record of the trial. Gene Kelly, best known for his dancing, portrays the character based on H. L. Mencken.)

Racial turmoil. In 1921 an incident occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that underscored the continued racial issues in the country that had begun almost as soon as the Civil War ended. It started when a black man was accused of assaulting a white woman. While he was incarcerated, a group of whites threatened to lynch him, and a group of black citizens went to the jail to try to prevent that from occurring. When the local sheriff urged the black man to disperse, saying that he would protect the prisoner, a confrontation occurred between the black-and-white groups, shots were fired, and then the sheriff reported that "all hell broke loose." As word of the confrontation spread, more violence erupted, and rampaging whites began to destroy property and kill more black people. At last the Oklahoma National Guard managed to restore order, but not before thousands of Blacks were left homeless, millions of dollars in property were destroyed, and many black-and-white people were killed. Even at the time the total number of casualties was disputed, but the numbers ranged as high as 200 among Blacks. For years news of the incident was suppressed, but eventually the full story became known. Along with the draft riots in New York City in 1863, the incident was one of the worst racial confrontations in American history.

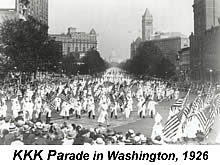

The Ku Klux Klan. The resurgence of the KKK in the 1920s is partially related to the two areas immediately above—Prohibition and religious controversy. It is no defense of the Klan to say that it was highly successful in selling the idea that it supported “American ideals” such as strong families, religious faith (Protestant, of course), and patriotism. Those otherwise admirable qualities had a dark side, however, as Klan members opposed immigration and leveled attacks against Catholics, Jews, “foreigners,” city dwellers, and anyone else who was not a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. They also attacked prostitution and other forms of immorality, as they described it. These appeals to “decency” attracted many good citizens, and Klan membership grew into the millions, though the real agenda of the Klan was often disguised during recruiting. In 1925 in Washington, D.C., some 40,000 Klan members held a rally and parade up Pennsylvania Avenue, and they rallied support against Catholic Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith in 1928.

These appeals to “decency” attracted many good citizens, and Klan membership grew into the millions, though the real agenda of the Klan was often disguised during recruiting. In 1925 in Washington, D.C., some 40,000 Klan members held a rally and parade up Pennsylvania Avenue, and they rallied support against Catholic Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith in 1928.

Despite their relatively benign outward message, the Klan still resorted to violence, particularly in places such as Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Indiana, and corruption among Klan leadership, generated in part by the wealth accumulated from dues-paying members, finally brought down the Klan. Following a scandal over the conviction of a Klan leader in a murder case, membership began to decline. By 1930 membership had declined drastically, but the institution did not die. Although attempts were made to revive the KKK following World War II, the organization has never been able to attract large numbers. Now, in the early 21st Century, the Klan still exists alongside other hate organizations such as so-called Neo-Nazi groups. Their numbers, thankfully, remain small. Since September 11, 2001, Muslims have come under attack from such organizations, despite the fact that Virtually all American Muslims deplore violence.

The Sacco-Vanzetti Trial. Another famous trial took place in Massachusetts in the 1920s. Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (left, in handcuffs), were convicted of killing a paymaster during a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in 1920. They were also believed to be anarchists, and as the case against them was not very strong, many believed (then and now) that they were unfairly convicted. (The judge had referred to the defendants as “those anarchist bastards.”)

The Sacco-Vanzetti Trial. Another famous trial took place in Massachusetts in the 1920s. Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (left, in handcuffs), were convicted of killing a paymaster during a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in 1920. They were also believed to be anarchists, and as the case against them was not very strong, many believed (then and now) that they were unfairly convicted. (The judge had referred to the defendants as “those anarchist bastards.”)

Italian anarchists had been implicated in the bombing of the home of Attorney General Palmer, and one of them was an associate of Sacco. Despite widespread protests from many quarters, and whether they were guilty or innocent, the two men were finally executed in the electric chair in 1927, while hundreds stood outside the prison in protest. The Sacco-Vanzetti affair has understandably been connected with the resurgence of “Nativism” at that time.

Nativism Revisited. Nativism first appeared, some have said, when the first colonists got off the boats and tried to keep the next boatloads from invading “their” turf. Actually Nativism took hold around 1845 when the first wave of Irish Catholics began to flood the country. Various Nativist groups organized political parties, including the Know Nothing Party, or tried to thrust their ideas onto the mainstream parties. The great wave of immigration through Ellis Island and other entry points up to World War I provided the stimulus for immigration restriction that worked its way into the Twenties.

About 800,00 immigrants arrived in the first full year of immigration after the World War, and a new immigration bill was passed in 1921. Then in 1924 Congress established far more severe limitations and quotas. The idea was to keep the majority of immigrants looking like the majorities that were already here. Thus Irish, Swedes, British, and Germans found it much easier to immigrate than Poles, Czechs, Greeks, and Italians. No immigrants were allowed from Asian nations. In 1929 immigration was limited to 150,000 annually, and most of the quotas went to Germany and the British Isles. Mexico was exempt from the quota restrictions, and many low-paid workers arrived from that country.

The Harlem Renaissance. The Twenties were not all negative by any means. The emergence of what has been called the “New Negro” was one of the highlights of the decade. Many Blacks began to take pride in their ethnicity, and a great outpouring of art, literature, and music from the hearts and minds of African Americans lifted not only Black culture but all of America. Writers such as Ralph Ellison (The Invisible Man), Langston Hughes, Zora Neal Hurston (Their Eyes Were Watching God), Richard Wright (Native Son), and others provided insight into the human experience as seen by Black Americans.

Before and during World War I, thousands of Blacks had begun to migrate to northern cities in search of better economic opportunities, and there they developed new, rich urban cultures, often segregated in fact (though not by law) from white communities. New York City’s Harlem is the most famous focal point of northern Black culture, but similar places existed in Detroit, Chicago, and other northern cities. A Black Nationalist Movement was also part of the Twenties as leaders like W. E. B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey struggled to expand civil rights and cultural pride in Black Americans. In the legal arena, the court system began slowly to dismantle the legal segregation that began in the aftermath of Reconstruction, but full liberation for Black people was still a long time away.

Race riots in the 1920s cast a shadow over the lives of African Americans, however, and groups such as the NAACP fought for passage of a federal anti-lynch law. Although they were unsuccessful, the publicity they generated did reduce the number of lynchings substantially. African Americans would have to wait until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s to see real changes in their status as citizens.

Race riots in the 1920s cast a shadow over the lives of African Americans, however, and groups such as the NAACP fought for passage of a federal anti-lynch law. Although they were unsuccessful, the publicity they generated did reduce the number of lynchings substantially. African Americans would have to wait until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s to see real changes in their status as citizens.

The 1920s was a decade of huge figures—heroes of the kind we rarely see any more. In 1927 Charles Lindbergh made his famous flight across the Atlantic, and the full story can seem as incredible today as it was at the time. Lindbergh took off from New York in an airplane that he himself helped design and build. Although he had been working frantically for days to prepare for the flight, he slept practically not at all on the night before he took off. His plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, which hangs in the Smithsonian today, was filled with gasoline in every empty space. Lindbergh had no navigation devices, no radio, nothing but maps, a bag of sandwiches, and a jug of water. Fighting fog, cold, and most of all fatigue, Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic Ocean and the English Channel, and after 33 1/2 hours he landed his plane in Paris. Within twenty-four hours the virtually unknown American flyer became arguably the most famous man in the world.

(The movie of Lindbergh’s feat, The Spirit of St. Louis, was overseen by Lindbergh himself, and the actor who portrayed him, James Stewart, was himself an Air Force pilot.)

A “Golden Age.” Americans started going to the movies and listening to the radio in enormous numbers, and they found themselves becoming more affluent as the markets rose, seemingly without end. If the Harlem Renaissance opened Americans to Black literature, poetry, music, and other arts of a quality never seen before, literary figures like Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe brought white American literature to a new plane as well. The first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, was produced in 1927; color moving pictures followed a few years later. Americans of that era loved film stars such as Charlie Chaplin, and they honored heroes such as Charles Lindbergh. They had more time to participate in and watch sporting events, and Babe Ruth became the first athlete to earn a salary of $100,000 for a season. When reminded that that was more than President Hoover made, the Babe replied, “I had a better year.”

Business in the 1920s

The Age of the Consumer. During the 1920s everybody seemed to be buying everything, and businesses set out to meet the demands of consumers, producing new products in record-breaking quantities. Cars, radios, appliances, ready-made clothes, gadgets, and other consumer products found their way into more and more American homes and garages. Americans also started buying stocks in greater numbers, providing capital to already booming companies. All the signs pointed upward, and starry-eyed men and women began to believe that it was going to be a one-way trip, possibly forever.

Henry Ford’s assembly line not only revolutionized production, it democratized the ownership of the automobile. Ford showed that handsome profits could be made on small margin and high volume. By 1925 his famous Model T sold for less than $300, a modest price by the standards of the 1920s. Americans had never had it so good. (Many, of course, would not have it so good again for a long time.)

Henry Ford’s assembly line not only revolutionized production, it democratized the ownership of the automobile. Ford showed that handsome profits could be made on small margin and high volume. By 1925 his famous Model T sold for less than $300, a modest price by the standards of the 1920s. Americans had never had it so good. (Many, of course, would not have it so good again for a long time.)

Thanks to pioneers such as Lindbergh, the airplane began to come of age in the 1920s. Although airplanes had been used for various modest purposes, mostly reconnaissance, in the World War, they were still exotic gadgets in 1920. In 1925 an Airmail Act provided for the use of airplanes as mail carriers through a competitive bidding system. After Lindbergh’s flight, planes began to carry passengers for travel rather than just for thrills. Regularly scheduled flights began, and airports were constructed to handle passengers and small amounts of cargo. American and United Airlines were two of the successful early airline companies. The end was in sight for railroad domination of the transportation industry.

Farming in the 1920s. Not everyone prospered in the 1920s. Farmers, becoming increasingly more skillful and efficient in producing food, found that laws of supply and demand still plagued them. Machinery began to replace animal power more and more, as tractors replaced horses and mules. But those large machines were expensive. The more farmers produced, the lower prices tended to fall. Personal food preferences changed as well, and Prohibition took grains used to make alcohol and used them for food crops. In the early 1920s bread was at its lowest price in five hundred years relative to other necessities. It was still tough to make a living down on the farm.

The U.S. government did attempt to assist farmers. For example, the government passed the Flood Control Act in 1928 to control floods along the Mississippi River, which had recently overflowed its banks, causing havoc among farmers in that area. During the 1920s about 27 percent of the U.S. workforce was in farming. Next Section: 1920s Politics

| Sage History Home | Twenties/Depression Home | The Crash of 1929 | The Depression | Updated August 15, 2021 |