James Madison & the War of 1812

Copyright © Henry J. Sage 2102

The Second War for Independence

James Madison as President

James Madison was a close friend and political ally of Jefferson. Madison's home, Montpelier, near Orange, Virginia, is about 27 miles from Monticello. Madison and Jefferson exchanged frequent visits when able, and their collected correspondence fills three hefty volumes. Madison was selected as Jefferson's successor by Republicans in Congress and won the election of 1808 easily. As Jefferson’s Secretary of State and closest advisor, Madison’s transition to the higher office was essentially seamless, yet he inherited most of the same problems with which Jefferson had been dealing.

James Madison is sometimes viewed as being temperamentally unsuited for leadership, but a closer examination of his performance at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, his term as Speaker of the House, as Secretary of State under Jefferson and as President reveals otherwise. While he was small in stature and lacked a strong speaking voice, he knew how to get things done. Dolley Madison, known for her physical attractiveness and cleverness at entertaining and decorating, was a sophisticated political companion who knew how to use her feminine charms in the service of her husband's political career.

James Madison is sometimes viewed as being temperamentally unsuited for leadership, but a closer examination of his performance at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, his term as Speaker of the House, as Secretary of State under Jefferson and as President reveals otherwise. While he was small in stature and lacked a strong speaking voice, he knew how to get things done. Dolley Madison, known for her physical attractiveness and cleverness at entertaining and decorating, was a sophisticated political companion who knew how to use her feminine charms in the service of her husband's political career.

Ever faithful to her “Jemmy,” Dolley entertained at the White House in a manner suggestive of the salons of Paris, collecting information and seeing to it that those who needed her husband’s ear could get it. Like many other great women in supporting roles, Dolley Madison served her husband and her country well. She is best known for having saved a famous portrait of George Washington from the British as they approached and then burned the White House in 1814.

For a good read about Madison and his contemporaries, including the women, try the fine book 1812 by David Nevin, a first rate historical novel. More About Madison & Montpelier.

Madison’s Foreign Policy. James Madison’s terms in the White House were dominated by foreign dilemmas—the last years of the Napoleonic Wars. Following the repeal of the Embargo Act, subsequent attempts to reduce tensions at sea included the Non-Intercourse Act, which was in effect from March 1809 to May 1810. It provided for non-importation or exportation against belligerent nations; it was directed against both France and England as trade with both nations was prohibited. Under the Act, trade with all other nations was permissible. Concerning France and Great Britain, trade could be resumed with whichever nation dropped its restrictions against the U.S. In general, American ships could go wherever they wanted.

Also under the terms of the Non-Intercourse Act, the United States committed itself to resume trade with England and France if those nations promised to cease their seizure of American vessels. On the basis of a pledge by a British official, President Madison reopened trade with England, but the British ignored the promise and seized American ships that sailed under Madison's direction.

Congress then passed Macon’s Bill Number Two, in effect from May 1810 to March 1811, another “carrot and stick” measure. It reopened trade with both Britain and France, but threatened new sanctions against either nation in the case of misbehavior, and trade with the other nation at the same time. Theoretically it provided flexibility, but in the face of repeated violations and “cheating” by both sides, it also proved ineffective.

Under this law Napoleon promised to respect American rights but subsequently broke his word; he had no intention of respecting American neutral rights. Instead Napoleon buffaloed Madison by having one of his ministers, M. Cadore, send an ambiguous letter containing various promises to revoke restrictions in exchange for American pressure against Great Britain. Madison informed Great Britain that non-importation would be re-invoked, but the British refused to repeal their Orders in Council. Non-importation was thus invoked against England from March 1811 to June 1812, an act which aided Napoleon’s Continental System.

In April 1809, British Minister Erskine, who was friendly to the U.S., negotiated a favorable treaty with the U.S., and President Madison claimed that all issues between the U.S. and Great Britain were resolved. Foreign Secretary Canning rejected the agreement, however, and the Americans grew angry and moved closer to France. Great Britain replaced Erskine with a tougher minister, “Copenhagen Jackson,” who was notorious for having ordered British ships to fire on the Danish capital. He repudiated the Erskine agreement, and Madison ordered him returned to Great Britain.

In a new incident at sea in 1811, an American ship, the U.S.S. President got into a scrap with the British Little Belt (left), which was badly battered. Meanwhile, the British had again begun arousing the Indians in the Northwest Territory. The Indian Chief Tecumseh and his brother, The Prophet, attempted to form an Indian coalition to unify resistance against the Americans. Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory led an expedition and defeated the Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The Indian Confederation collapsed, but the American victory sent Tecumseh and his warriors over to the British side.

In a new incident at sea in 1811, an American ship, the U.S.S. President got into a scrap with the British Little Belt (left), which was badly battered. Meanwhile, the British had again begun arousing the Indians in the Northwest Territory. The Indian Chief Tecumseh and his brother, The Prophet, attempted to form an Indian coalition to unify resistance against the Americans. Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory led an expedition and defeated the Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The Indian Confederation collapsed, but the American victory sent Tecumseh and his warriors over to the British side.

By 1812 troubles between the United States and Great Britain (and France, to a lesser extent) had reached a point of no return. Although the War of 1812 has been called the least necessary of all American wars (at least until Vietnam), in retrospect the American government under Jefferson and Madison pursued reasonable (if somewhat ineffective) policies in defense of America's neutral rights. It was true that great profits could be earned through trade in time of war, and greed was no doubt a factor that pushed American merchant captains into repeated confrontations with both nations. Still, nations have a right to carry on business even when part of the world is at war.

The major goal of American foreign policy during this era was to try to give the President enough flexibility so that he could punish nations that treated us badly and reward those who were more cooperative. Unfortunately Great Britain and France were locked in mortal combat, and neither was inclined to be cooperative with anybody, least of all the fledgling new republic across the ocean.

In the end, British domination of the seas was the factor that put the Americans most at odds with them. Though the French behaved almost as badly as the British, an American war with France was unlikely, first because a French invasion of America (or vice versa) was virtually out of the question; the Atlantic Ocean was too great a barrier. Furthermore, impressment of American sailors was hardly practiced by the French, and leftover antagonisms from the Revolution still rankled both Americans and the British. Americans continued to blame their troubles on the British. For all their differences, France had been America's ally in winning independence, something Americans were unlikely to lose sight of. ("God forget us, if we forget/the sacred sword of Lafayette" became a well-remembered epithet for much of American history.)

The “War Hawks”

The 1810 election brought a group of new congressmen to office, the “War Hawks.” They were southerners and westerners who were strong nationalists, including Henry Clay of Kentucky, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, and Felix Grundy of Tennessee. These patriots from the frontier regions were offended by the depredations of the British, even though they were far less directly affected by them than were the merchants and ship owners of New England. In addition, the country was suffering an economic depression, a situation exacerbated to some extent by trade problems.

Furthermore, Americans, who were always hungry for more land, had looked with envy upon the rich portion of southern Canada in the Great Lakes region. War with England, it was felt, might well bring the Canadian provinces into the American fold. (Americans mistakenly assumed that Canada was ripe for rebellion against the mother country.) In any case, patience with Great Britain eventually wore thin, especially in the West, in the face of repeated violations. New Englanders, however, opposed the war, which would end all trade for the duration of the conflict. The old Federalist Party was not quite dead.

In the end there was much resistance to war: the vote for the declaration of war in Congress was 79-49; every state delegation in Congress from Massachusetts to Delaware came down against the war declaration. The southern and western delegations were almost unanimously in favor and “gave the East a war.” In 1810 a group of Americans in West Florida seized control from Spanish authorities and declared the “Republic of West Florida”; this was the only territorial conquest relating to the War of 1812. The Florida question would be opened again following the end of hostilities.

The WAR of 1812: The “Forgotten War”

General. Many Americans probably think that the “1812 Overture” was written to commemorate the war of 1812, especially since it is often performed on the 4th of July to the accompaniment of bells and cannon. In fact, the work was written by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky to celebrate Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in that year. That faulty connection, however, is not as wrong as it may seem.

In the first place, the War of 1812 has often been called a forgotten war, with good reason. Few Americans know very much about the War of 1812 beyond the fact that it was fought with the British and that there was a Battle of New Orleans involved. Some may also associate the burning of the White House or the writing of the Star Spangled Banner with the war, but only vaguely. Part of the reason for that vagueness may be that the war changed very little in America: The end of the war restored the status quo ante bellum, that is, it left everything the way it had been when the war began. In addition, the end of the war coincided with the end of the Napoleonic wars (the War of 1812 ended six months before Waterloo) and was thus overshadowed by the greater events going on in Europe. Added to that overshadowing is that fact that with a few notable exceptions, the Americans did not always fight well, even allowing their capital to be burned by the British in 1814.

The second reason why the confusion with the events in Russia in 1812 is understandable is that the two events were in fact related. The War of 1812 began as a result of the fighting in Europe, which left America, a neutral nation, besieged by major players France and England as it tried to carry on normal trade in abnormal times. The war, in other words, was fought on the American side largely over neutral rights, although issues such as national pride, economics and regional politics certainly played a part in the decision to declare war. The fact of the Napoleonic wars also helped determine the way in which the British fought the war. They felt that Napoleon was a far greater danger to the world than any minor acts of interference (as they saw it) they might have committed with regard to American trade. They felt bitter toward their American cousins for declaring war while they had their hands full with France.

There are many reasons why Americans do not really celebrate the War of 1812. In the first place, the war did not change anything, exceptfor the men who died and theri families. The war did, however, produce its share of victories and heroes—most famously, Andrew Jackson at New Orleans. In the end, however, the most important result of the War of 1812 may have been the fact that placed America on the world stage at a level which had not been achieved by the Revolution. The American experiment was considered just that, an experiment, and many Europeans fully expected the new nation to fail, as it well might have. The War of 1812 has thus been called with some justification America’s second war for independence—an assertion of America's position as a nation worthy of respect.

At the start America was woefully unprepared for conflict. There was lack of unanimity over the causes, organization was poor, and militia forces—a necessary adjunct to the regular professional army—displayed a general unwillingness to go beyond their own state borders to fight. Few strong leaders remained from the Revolutionary generation, and early encounters with the British, though they were still distracted by Napoleon, were disastrous.

Nevertheless, American sailors were very capable, and American soldiers, when well led, were prepared to fight. However poorly the Americans fought the war, they did indeed fight it, growing stronger as the war progressed. At worst they achieved a stalemate. New leaders such as Andrew Jackson, Oliver Hazard Perry, Thomas MacDonough and Winfield Scott emerged. Had the war gone on longer, the Americans might well have given the British more significant defeats besides the Battle of New Orleans. Finally, no matter how sharply Americans were divided over the war early in 1812, the end of the war brought the “Era of Good Feelings.” Although the term is perhaps an exaggeration, it nevertheless points to the fact that that America had come through the war essentially intact.

Despite the losses, America probably gained more than it lost from the war. If nothing else, the conduct of the war left the powerful lesson that wars should not be entered into lightly or for the wrong reasons, and that it is best to be prepared for war before the fighting begins rather than having to improvise once hostilities have actually begun. The latter lesson is one Americans have had to “learn” several times.

Review: Chronology of Events leading up to the War.

U.S. Objectives of the War of 1812 were as follows:

- Get the British to repeal their Orders in Council, which placed severe trade restrictions on the Americans.

- Get the British to stop the impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy.

- Assert Americans' rights to freedom of the seas. (See Madison’s War Message to Congress.)

Despite early optimism, American war efforts were marred by poor preparation and management, ineffective leadership, and an ill-designed strategy. Americans expected victory even though unprepared. President Madison had problems in his administration beyond his control, and by the end of the war the Americans were getting their house in order. In New England, where the Federalists were still strong, people refused to take an active part in the war effort. Great Britain was in a state of turmoil politically, which helped bring the war about and contributed to its conduct by the British. King George III was by then totally insane, and the Prime minister (Spencer Percival) had been killed. Preoccupied with Napoleon, Great Britain appeared ineffective in executing offensive operations, which was fortunate for the Americans.

The Military Campaigns

The United States Army in 1812 was small, and state militias proved inadequate to fight well-trained veterans. Early campaigns were designed to take Canada, an appealing goal because of the abundance of land, the lucrative fur trade and problems with Indians. All the early Canadian campaigns were unsuccessful, however. General William Hull invaded Canada in July 1812 but was  forced to surrender to British Major General Isaac Brock in Detroit. Brock then moved to the eastern end of Lake Erie where American General Stephen Van Rensselaer was attempting unsuccessfully to invade. A third attempt at invasion failed when General Henry Dearborn’s New York militia troops refused to enter Canada.

forced to surrender to British Major General Isaac Brock in Detroit. Brock then moved to the eastern end of Lake Erie where American General Stephen Van Rensselaer was attempting unsuccessfully to invade. A third attempt at invasion failed when General Henry Dearborn’s New York militia troops refused to enter Canada.

In 1814, England planned a three-pronged attack on the United States: a march from Canada into the Hudson River Valley, an amphibious assault on the Chesapeake Bay region, and occupation of New Orleans. The decisive campaign was in New York State. General Sir George Prevost led a British force into New York and advanced to Plattsburg. Although he outnumbered the American garrison there, when American sailors under Commodore Thomas McDonough defeated the British on Lake Champlain, Prevost withdrew.

Meanwhile, British Admiral George Cockburn was conducting operations in the Chesapeake Bay area, raiding towns along the coast. In August 1814 he marched on the capital and handily defeated the American militia in the Battle of Bladensburg, Maryland. Dolley Madison saw to the saving of valuables, including a portrait of George Washington, even as James Madison was forced to flee the presidential mansion. British General Ross ate the dinner which had been prepared for the president, drank a toast to “Little Jemmy,” and set fire to the building. The next day British troops burned many more buildings in Washington.

The British then advanced on Baltimore, but were unable to reduce Fort McHenry, which had been built following the American Revolution to protect the Baltimore harbor. British warships bombarded the fort for over 24 hours, but were unable to penetrate the harbor, which was also protected by chains and sunken ships. The strong stand at Fort McHenry led Francis Scott Key, who observed the bombardment through a long night as bursting shells illuminated the flag, to compose his famous anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The Battle of New Orleans

During the War of 1812 a conflict erupted in the Southwest involving a faction of the Creek Indians known as the “Red Sticks.” When Indians attacked Ft. Mims in the Alabama territory and killed several hundred residents, Major General Andrew Jackson led the Tennessee militia in a series of battles against the Creeks that ended at Horseshoe Bend in March, 1814. In May Jackson was  named American commander in the New Orleans area, just as the British were planning to take New Orleans with a large force of 7,500 veterans under Sir Edwin Packenham. The British planned to take control of the entire Mississippi River Valley.

named American commander in the New Orleans area, just as the British were planning to take New Orleans with a large force of 7,500 veterans under Sir Edwin Packenham. The British planned to take control of the entire Mississippi River Valley.

A nighttime raid by Jackson’s men disrupted Pakenham’s march on the city from the east, and Jackson then took up a strong position south of New Orleans between a Cyprus swamp and the east bank of the Mississippi. Jackson’s force was a motley collection of Tennessee and Kentucky sharpshooters, members of Jean Lafitte’s pirate band and various volunteer groups of Creoles and fire brigades from the city. He quickly constructed heavy breastworks along his defensive position that offered good firing positions for artillery and riflemen. Jackson’s flank were protected by the Mississippi River and the Cyprus swamp.

On the morning of January 8, 1815, Packenham’s force of over 5,000 redcoats disembarked below Jackson's position and prepared to advance. Veterans of campaigns against Napoleon's troops, the British were confident of swift victory and expected to dispatch the Americans without difficulty. They advanced confidently upon Jackson's entrenchments, but were met by a rude shock. Behind the parapets (which can be seen in the picture) were 4,500 defenders, many of them expert rifleman. They waited for the attacking British to get well within range and then let loose a furious volley of artillery and rifle fire. The redcoats were cut down unmercifully, and Packenham himself was killed. The British suffered over 2,000 men killed and wounded; the Americans had eight killed and 13 wounded.

The Battle of New Orleans was one of the most one-sided victories in all of American military history, and although it had no direct impact on the war, it was a huge morale booster for the Americans, and created a hero in Andrew Jackson, which would eventually result in his election to the nation's highest office. The great irony of the Battle of New Orleans was that it actually took place after the peace treaty had been signed, but there was no way to communicate the news in time to prevent the battle. The Chalmette Battlefield is about seven miles south of the city of New Orleans. Jackson’s battlements are well preserved, and it is easy to see how the British were hemmed in by the swamp and the Mississippi River.

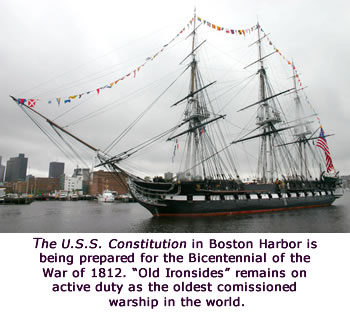

The Naval War. Although badly outnumbered, the U.S. Navy nevertheless distinguished itself during the War of 1812. New shipping was needed but was not built in at the outset of the war; thus the American blue-water Navy collectively was generally ineffective against the much larger Royal Navy. On the other hand, the American ships that were already in operation were better suitedthan British ships for one-to-one combat. The U.S.S. Constitution (left) under Captain Isaac Hull defeated H.M.S. Guerriere on August 19, 1812, in one of a number of individual ship victories for the Americans. American privateers did very well; 148 “legalized pirates” captured 1300 British ships, damaging the British cause. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory on Lake Erie secured the Northwest Territory firmly under American control. Another fleet victory by Commodore Thomas Macdonough on Lake Champlain turned back the attempted British invasion from Canada in 1814.

The Naval War. Although badly outnumbered, the U.S. Navy nevertheless distinguished itself during the War of 1812. New shipping was needed but was not built in at the outset of the war; thus the American blue-water Navy collectively was generally ineffective against the much larger Royal Navy. On the other hand, the American ships that were already in operation were better suitedthan British ships for one-to-one combat. The U.S.S. Constitution (left) under Captain Isaac Hull defeated H.M.S. Guerriere on August 19, 1812, in one of a number of individual ship victories for the Americans. American privateers did very well; 148 “legalized pirates” captured 1300 British ships, damaging the British cause. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory on Lake Erie secured the Northwest Territory firmly under American control. Another fleet victory by Commodore Thomas Macdonough on Lake Champlain turned back the attempted British invasion from Canada in 1814.

Future President Theodore Roosevelt wrote The Naval War of 1812 at age 23. Written in 1882, it remains a fine account of the action by the U.S. Navy and includes a chapter on New Orleans.

THE TREATY OF GHENT

After the American victory at Plattsburg on Lake Champlain, the English government decided to enter negotiations to end the war without addressing any of the issues that had caused the war. The Duke of Wellington also advised the British government to abandon the war. As much of the war had gone badly for the Americans, Madison was also ready to negotiate, and sent a peace party consisting of, among others, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay to the city of Ghent in Belgium, where discussions were to be held. Both sides were weary of the war, and an agreement was reached to end the war and restore the status quo ante bellum—the state in which things were before the war. (That agreement did not, of course, restore life to those who were killed nor repair property destroyed.) American efforts were aided by the Duke of Wellington, the British victor over Napoleon at Waterloo, who advised Great Britain to abandon the war.

The Treaty of Ghent, signed on Christmas Eve 1814, thus ended the deadlock of war with no major concessions granted by either side. The belated American victory at the Battle of New Orleans led to a widespread conception that the United States had won the War of 1812, and the Senate ratified the treaty unanimously. For Americans, the war succeeded splendidly. They had won a “second war of independence.” Even after the treaty had been signed, GreatBritain considered the war a stab in the back—they still saw the Yankees as “degenerate Englishmen.” The British victory at Waterloo and the American victory at New Orleans, however, detracted from bad feelings on both sides. In addition, the end of the Napoleonic wars rendered issues such as impressment and neutral rights moot.

The Battle of New Orleans and the Naval War of 1812 demonstrated that American soldiers were capable of fighting when well led, and that American ships and sailors were very good.

In the end, America probably gained more than it lost from the war. If nothing else, the conduct of the war left powerful lessons: Wars should not be entered into lightly or for the wrong reasons; it is best to be prepared for war before the fighting begins rather than having to improvise once hostilities have actually begun. The latter lesson is one Americans have had to “learn” several times.

THE HARTFORD CONVENTION: Further Hints of Secession

Resentment felt by New Englanders over Jefferson’s Embargo grew during the Madison administration; the so-called “Essex Junto” was still alive and kicking, though the actual membership had changed with time. When the war seemed to be going badly for the United States, a group of Federalists met in Hartford, Connecticut, in December 1814. They recommended changes in the Constitution that would have lessened the power of the South and the West. Many New Englanders were more than disenchanted with what they viewed as the “Virginia Dynasty.” (With the exception of the single term of John Adams, only Virginians had occupied the office of president since 1789.) Fortunately, more moderate voices prevailed; talk of secession and a Northern confederacy gained no traction. The Convention did, however propose several constitutional amendments:

- Abolish the 3/5 Compromise (Reduce Southern power in Congress.)

- Require 2/3 of the Senate approval to declare war. (One third of the states could then veto a war declaration.)

- Place a 60-day limit on any trade embargo.

- Permit presidents to serve only one term.

- Do not allow a president to succeed another president from the same state. (Prevent another “Virginia dynasty.”)

Unfortunately for the Federalists, they met on the eve of the conclusion of peace. Their proposal arrived in Washington more or less simultaneously with news of the Ghent Treaty and the victory at New Orleans. After those events, the Convention's demands seemed irrelevant and disloyal. The proposed amendments never went anywhere, and the Federalist Party never recovered from the Hartford Convention. In the end, the Treaty of Ghent discredited the Federalists and killed their party. The net result was that the War of 1812 discredited the Federalists and brought an end to the party's existence.

Aftermath of the War of 1812.

Although there were no “fruits of victory” following the war, some benefits did accrue to the United States, even though there was no victory. The American performance in the war, especially after Jackson’s overwhelming triumph in New Orleans, was convincing to Europe. The war brought an end to Barbary tributes, and freedom from harassment by pirates. As so often happened throughout American history, the Indians were the big losers. They backed the wrong side in the conflict—it was not the first time, nor would it be the last. Significant for all the Western world was the final defeat of Napoleon, which began a period known as the “Hundred Years’ Peace.” It began in Europe with the Congress of Vienna and continued more or less uninterrupted (with limited exceptions) until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

Madison’s term ended on a fairly positive note. Whether it was a victory or a lucky draw, the American people felt satisfied with the results of the war, largely because of Jackson’s victory at New Orleans and several spectacular naval triumphs. Further, the old Federalist Party was now all but gone, and a new “Era of Good Feelings” was ushered in. Threatening talk about the “Virginia Dynasty” gradually died out.

James Madison’s legacy is still being debated, but in general it can be said that he was one of the key figures in the creation of the American Republic. He seems to many historians to be moving out of the shadow of his more famous Virginia brethren, and well deserves his title of “Father of the Constitution.” He lived until 1836, the last of the great men of that era to pass on.

Books on the War of 1812 Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, 1989. Taylor, Alan. The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies, 2010. Daughan, George C.. 1812: The Navy's War, 2011 Nevin, David. 1812 (The American Story) , 1997. 1812 by David Nevin is a work of fiction, but it offers a readable account of the war. It is a fine historical novel. |

| Jeffersonian Home | Jacksonian Home | American Economic Growth |

| Sage American Home | Antebellum America | Updated December 13, 2013 |