Technology: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The centuries-old technological revolution has reached a new phase: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

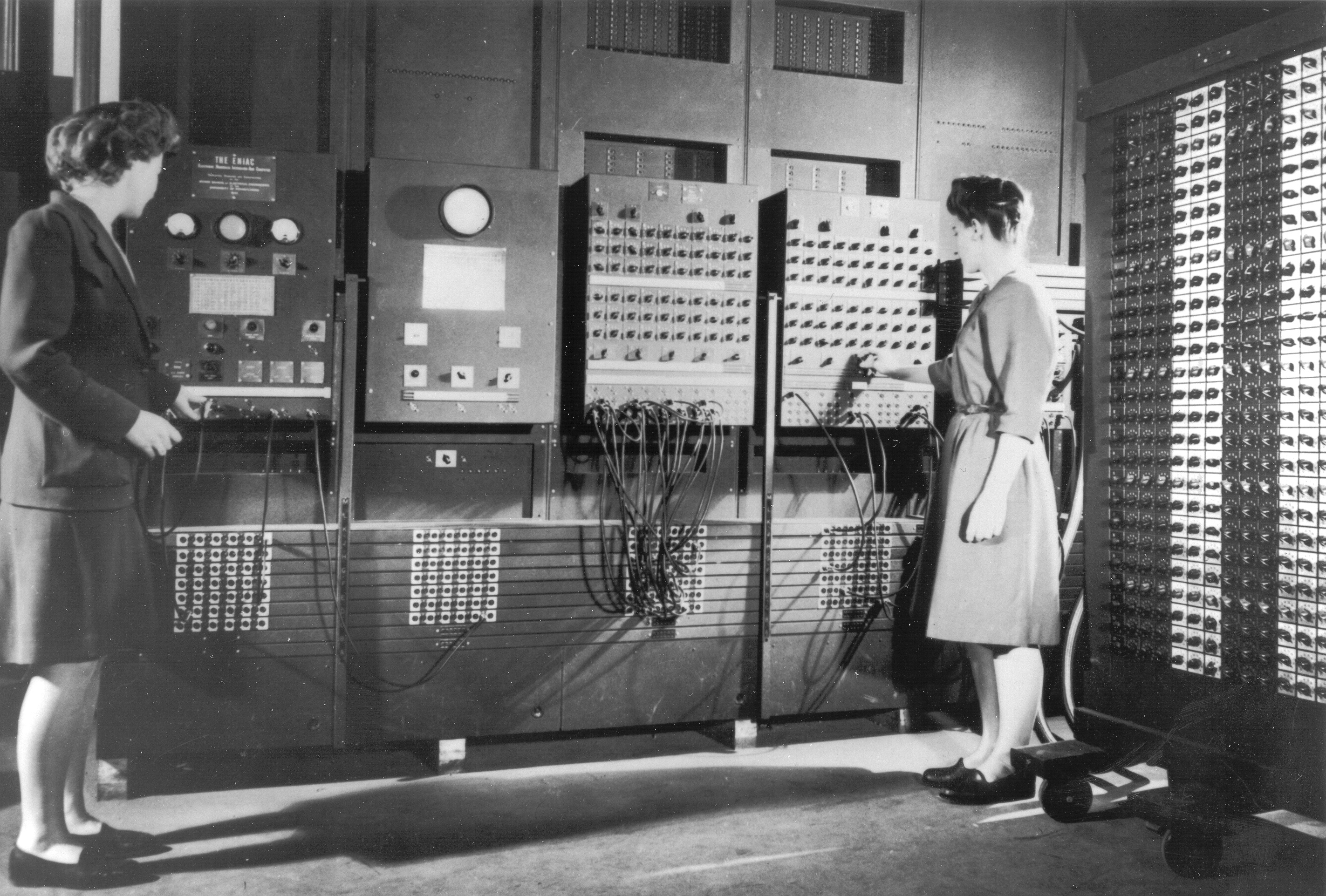

We are now decades into the computer age. The first programable computers appeared before World War II. The Turing machine was conceived in 1936 and finally built during World War II as a step toward breaking the German enigma code, which aided the allies in predicting German military moves. The first digital computer, the ENIAC (below left), was completed in 1946. It was a huge machine that weighed 50 tons and had 18,000 vacuum tubes. More large computers were built in the 1950s by IBM and other companies. Smaller personal computers began to be developed in the 1970s, and the first IBM personal computer was built in 1981. Other companies such as Compaq began to copy it, and the Apple company was also developing personal computers. By the 1990s personal computers had become ubiquitous, and teachers and other professionals started using them regularly in their work.

By today's standards those early PCs were clumsy and slow. Sending email required several steps, and communication between computers was limited. Then the World Wide Web was invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1993, and the computer world began to take off. People began creating websites using HTML code, which required some learning, and then more sophisticated web building programs began to appear. Companies like Netscape, Adobe and Macromedia put out advanced programs that enabled website builders to create dynamic sites with graphics without having to write a lot of code.

By today's standards those early PCs were clumsy and slow. Sending email required several steps, and communication between computers was limited. Then the World Wide Web was invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1993, and the computer world began to take off. People began creating websites using HTML code, which required some learning, and then more sophisticated web building programs began to appear. Companies like Netscape, Adobe and Macromedia put out advanced programs that enabled website builders to create dynamic sites with graphics without having to write a lot of code.

The first computer I owned was a Kaypro 1. It had a black screen with green type about the size of a 3 x 5 card and was very limited in what it could do. Even sending an email required multiple steps. When our college provided desktop computers for faculty for classroom use, I began building a website in 1995, the predecessor of the one you are looking at now. For me it became a useful adjunct to lecturing in the classroom, as I could put material on the website that students could consult between classes. It gave me more freedom to interact with students—if they wanted to discuss a topic in more depth than I had planned, which might mean that we would miss part of the planned lesson, I could place extra material on the website for them to read later.

The use of computers and related devices began to expand rapidly around the turn of the century during the period known as the dot com boom. New companies and programs appeared, and older models were swept aside. When cell phones began to adopt computing methods, the world we now call cyberspace expanded exponentially. Eventually companies like Facebook, Twitter, Apple, and Alphabet--the parent company of Google--dominated the marketplace and allowed the rapid transmission of large quantities of information, including music, photos, and movies. The arrival of those companies was greeted with much fanfare, a promise that they would help people live richer and more fulfilled lives by allowing them the to communicate with friends and family across wide distances.

Like everything from gunpowder to atomic power, however, those modern technologies could be used for good or ill. As massive amounts of information began to be exchanged, the reliability of the content exchanged was called into question. People could publish false information or level phony claims against individuals with very little oversight from the big companies, who were making billions of dollars in advertising by selling user information. An early motto of Facebook was, "Move fast and break things," which reveals an underlying reckless disregard for the damage that might be done by the proliferation of false information. The competition among these companies was fierce, and as each one developed a new technique, the others rushed to copy it.

As it became apparent that these giant companies, as well as a number of smaller ones, allowed the spread of erroneous or even destructive information, voices began to be raised against the philosophy that the free, unmonitored exchange of information is a good thing. The applications, or apps, used in these programs or loaded onto telephones were constructed to encouraged repeated use; in other words, they were deliberately created to be addictive. Advertising based on user information proliferated, and programs began tracking people’s locations, looking at emails, tracing phone calls and doing everything possible to glean as much possible information from users as could be done legally.

Businesses used personal preferences to attract customers, and political parties used the data to spread information about candidates running for election. At the same time, hate groups and other malevolent actors used the same tools to garner new members or supporters. It soon became apparent that not only were agents in the United States spreading questionable information, but many foreign actors got into the act. Evidence was discovered that Russian agents attempted to manipulate the election of 2016. A few days before that election, Roger McNamee, a venture capitalist friend of Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, advised him of the evidence of that Russian activity on Facebook. Zuckerberg did not respond.

More recently, other observers of the cyberworld have raised concerns about the effect that this constant drumbeat of questionable information, as well as its addicting qualities, were beginning to have negative effects on users, especially children. A teacher in a local public high school told us about the ordinary efforts they must use to get students put away their cell phones or laptops and concentrate on the lessons in the classroom. Employees of some of the larger companies like Facebook and Google began having doubts, and some of them published essays or wrote books warning of the dangers of allowing these practices to continue unabated.

In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, Shoshana Zuboff argues that private corporations and not government are using our private information for profit. She describes the way capitalism evolved: People took natural resources, everything from land, to raw materials, to their own creativity to create objects of value. Land produced timber, which became lumber for building homes. Iron and other ores were mined and converted into metals used to construct everything from bridges to automobiles to household appliances and jewelry.

Her argument focuses upon the fact that it is now our personal information, the very essence of our lives, that has become the raw material for capitalist companies to use and sell for profit, often without our knowledge or permission. Smart devices in our homes—televisions, refrigerators, devices like Amazon’s Alexa—compile information and send it out where it can be sold to the highest bidder. In an extreme example, talking play toys record children’s conversations and transmit them for use in creating voice recognition programs for surveillance by agencies such as NSA.

It works something like this: Let's say that a you and a group of your friends are at lunch planning what you're going to do for your summer vacation. You talk about where you're going and why—maybe the beach, maybe the mountains, maybe an island in the Caribbean—and mention when you're going to leave, when you'll be back, on what airline you will be flying, and so on. In order to keep track of each other you exchange addresses and phone numbers, and over the course of your lunch you share a number of more personal details about your favorite books, movies, foods, restaurants, etc. You might even exchange information about someone who has recently had a medical condition, or gotten a divorce, or been fired, or anything else that you would prefer to keep private.

It works something like this: Let's say that a you and a group of your friends are at lunch planning what you're going to do for your summer vacation. You talk about where you're going and why—maybe the beach, maybe the mountains, maybe an island in the Caribbean—and mention when you're going to leave, when you'll be back, on what airline you will be flying, and so on. In order to keep track of each other you exchange addresses and phone numbers, and over the course of your lunch you share a number of more personal details about your favorite books, movies, foods, restaurants, etc. You might even exchange information about someone who has recently had a medical condition, or gotten a divorce, or been fired, or anything else that you would prefer to keep private.

Now let's say that in the next booth there's a guy with a recorder and a hidden camera who filming and recording everything you say. He takes that information down to your local newspaper, sells it to them, and next day it's on the front page of the Metro section. Here the newspaper is a metaphor for the giant companies that do exactly what was just described. They collect personal information and sell it to companies to use for advertising. So if one of you said that he or she was going to vacation in Puerto Vallarta, they would start getting ads for hotels in Puerto Vallarta and the airlines that fly there. A lot of people have no problem with that. But there is an issue; if you change your mind and decide to go somewhere else, you keep getting all the ads for Puerto Vallarta.

That last transaction, the selling of your personal information for profit under the conditions I just described would be done without your knowledge or permission. But that happens all the time. And now a new player has entered the game: Zoom. It's nice that people can get together virtually in these troubling times. But an article by a technology reporter recently had the headline: “Zoom is Easy. That’s why it's dangerous.” The author pointed out that just like the other big companies, they have done little to prevent people for using zoom to congregate hate groups, intrude on other people's meetings, and so on. The article points out that “ease of use is also a root cause of ‘Zoombombing’—harassment through the suddenly popular video-calling app.”

While a number of people are bothered by these developments, evidence shows that the majority of Americans are perfectly content to allow these companies to do what they are doing. Congress has held hearings on the subject of privacy protection, but to date there has been no legislation designed to put limits on the amount of private information that can be gathered and distributed by those companies at will.

So the question remains: How much will the widespread, uncontrolled use of high technology balance the benefits with the obvious damage that is being done? Will corporations start policing themselves, or will government step in with effective legislation? At this juncture, no answers seem to be in the offing.