The United States in World War II (Continued)

Copyright © Henry J. Sage, 2012

Hiroshima: The Atomic Age Arrives

President Harry Truman, who became president upon FDR’s death in April 1945, was unaware of the Manhattan Project at the time of his accession, having been left in the dark by President Roosevelt. Shortly after Truman was sworn in, Secretary of War Stimson approached him with details of the ongoing project. He described the work on a weapon of terrible destructive power, which had not yet been tested. While the President, along with Secretary Stimson and other top advisors, was attending the  conference at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 where he met with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, he received word that the A-bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman authorized the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. President Truman’s decision has been criticized in hindsight, but the decision never seemed to trouble him, even years after. The president had been advised that an invasion of the Japanese homeland, which was scheduled to begin in November 1945, would cost thousands of American and Japanese casualties.

conference at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 where he met with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, he received word that the A-bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman authorized the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. President Truman’s decision has been criticized in hindsight, but the decision never seemed to trouble him, even years after. The president had been advised that an invasion of the Japanese homeland, which was scheduled to begin in November 1945, would cost thousands of American and Japanese casualties.

The atomic bomb promised to bring an end to the fighting immediately. After debate among his advisers and objections from some of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, President Truman decided to go ahead with the attack. On July 25 the decision was made to order the dropping of atomic bombs on selected Japanese cities. Secretary Stimson and General Marshall sent the order to drop the bombs to Army Air Force’s special air group on Saipan. Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (left) had managed the Manhattan project since 1943 and had overseen the successful Trinity test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in July.

The first atomic weapon was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Authorization for further attacks was included in the initial directive. The Hiroshima explosion cut off all communication from the city. It was only after a special air reconnaissance from Tokyo had returned from Hiroshima that officials in Tokyo were aware of the damage. Japanese authorities did not meet until August 8 to discuss a response, and opinion was divided. Some Japanese officers doubted that another bomb existed and argued that Japan should fight on. On August 9 the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and launched an attack on Manchuria. Later that day the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Refusing to admit defeat, the Japanese generals argued for a fight to the death, and an attempted military coup was narrowly averted. But within hours of the Nagasaki attack, Japanese Emperor Hirohito, refusing to accept any further destruction of his land and his people, decided to surrender. Despite a last minute rebellion by some generals, the emperor broadcast his decision to the Japanese people on August 14. The long and bloody conflict was finally over.

(An excellent film about the last days of the war, viewed from both the American and Japanese side, Hiroshima, was released in 1995. The film, directed by Roger Spottiswoode and Koreyoshi Kurahara, was a joint production of Canada and Japan; it received many honors.)

Nobody knows how many human beings died as a result of World War II, but the figure is in the tens of millions. Recent estimates place the total between 56 and 72 million. The Soviet Union lost over 20 million, China over 10 million, Germany 6 to 8 million, Japan 2.7 million, the United States and Great Britain something less than half a million each. Most of the combatant nations incurred significant numbers of deaths, and even neutral countries were not immune to the human destruction. The majority of those deaths were directly attributable to the war itself, but millions more were caused by an evil even greater than war: the deliberate murder of human beings as a matter of national policy.

Although he did not spell out the details, Hitler proposed a radical solution to what he called the “Jewish problem” in Mein Kampf. Although his book was widely sold, it was not widely read, and in any case even those who read it would have had difficulty foreseeing what actually occurred. Starting with Kristallnacht, the SS and Gestapo began rounding up Jews by the thousands and shipping them off to concentration camps. There were no legal proceedings or trials involved; once a person was identified as a Jew, he or she was subject to arrest with no attendant judicial process.

The Nazi government had started creating concentration camps as soon as it came to power in 1933. By 1939, six large camps existed, including Dachau (1933), Sachsenhausen (1936) and Buchenwald (1937). The most notorious of the concentration camps, Auschwitz, was created after the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. Those who were fit for work were used as forced labor from the beginning of the war. Those who were sick or infirm or otherwise incapable of being productive were summarily executed. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Hitler’s generals and officials expected a rapid end to the war and gave little thought to the ultimate disposition of the Jewish and other prisoners in the concentration camps. Early in 1942, however, with the United States in the war and German armies bogged down in Russia, a conference was called at Hitler’s direction to establish a “final solution” for the Jewish problem.

The Head of the Gestapo, Reinhard Heydrich, issued an invitation to representatives of all German government departments concerned to a conference at Wannsee in January, 1942. In attendance were representatives of the departments of Justice and the Interior and others. The recording secretary was Adolf Eichmann. Heydrich ran the meeting with ruthless efficiency and issued blunt instructions to all attendees to cooperate in the extermination of the entire Jewish population of Germany and Eastern  Europe. By 1942 hundreds of large and small concentration camps existed in every German occupied territory.

Europe. By 1942 hundreds of large and small concentration camps existed in every German occupied territory.

Although killings were carried out by shooting early in the war, the large number of prisoners to be killed required more efficient methods. Poison gas and exhaust fumes from diesel trucks were the methods most commonly used. Bodies were disposed of in mass graves or burned in crematoria. Many Jews and other prisoners died on their way to concentration camps as they were locked in rail cars without food or water, often for days or even weeks at a time. As the German army advanced in the East, special SS units were deployed to round up Jews and other “undesirables” and execute them on the spot. Prisoners were ordered to dig mass graves in the earth and were then shot. Bulldozers were used to push bodies into the graves and cover them with dirt.

The literature on the Holocaust is vast. The total number of Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, communists, people with mental and physical handicaps, and others will never be reckoned, but the total was at least 10 million, of whom 6 million were Jews. The Holocaust was deliberate, state-sponsored genocide, one of the greatest humanitarian tragedies and most horrific acts in the history of the world. Despite massive evidence in the form of documents, photographs, films, and the testimony of survivors, there are still those who doubt that the holocaust occurred, or who claim that the number of people killed has been hugely exaggerated. Institutions like the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington DC attempt to tell the real story of what happened, but there are still those who doubt.

At the rear entrance to the Museum is a plaque with a quote from General Eisenhower, who visited the concentration camps after the war was over. He told General Marshall:

“The things I saw beggar description….The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty, and bestiality were…overpowering….I made the visit deliberately in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’”

General Eisenhower was wise enough to foresee what actually came about. The above quote is on a plaque in the Plaza on the 15th street side, shown in the photo..

Reflections

I grew up near New York City during World War II and recall quite vividly many of the things that were taken for granted as part of the war situation. For example, people on the East Coast were concerned about the possibility, however remote, that we might be attacked from the air by Germany. A submarine was spotted off the coast of Long Island, and although the Germans did not have aircraft carriers, the possibility of an air raid was taken seriously.

Thus I recall regular air raid drills in our neighborhood. Responsible citizens would be designated air raid wardens, and when the sirens went off at the village firehouse, people were obliged to either turn off all their lights or completely pull down opaque shades that would prevent light from escaping. The warden, wearing a protective helmet, would patrol the neighborhood on foot with a flashlight (all streetlights were turned off) and politely correct all those who perhaps allowed a small beam of light to escape from a window. In our block during warm weather the neighbors would sit on their porches smoking cigarettes and listening to the latest news on the radio. (Everybody smoked, and television had not yet arrived.)

Automobiles were allowed to drive during air raids, but the top halves of all automobile headlights had to be painted black. And there were, in fact, very few automobiles on the road in those days. With gasoline and rubber tires being strictly rationed, people drove as little as possible. Many good citizens simply put their automobiles up on blocks for the duration of the war and did not drive them again until it was over. I recall driving with my uncle, who would turn his engine off and coast every time he was moving downhill in order to save a few drops of gasoline.

Meat, butter, sugar, and certain other commodities were rationed because the fat content was needed to make explosives or provide for other war-related needs. Recycling was big during World War II, a phenomenon that disappeared for a few decades until environmental issues came to the fore. But we saved newspapers, tin cans, and all sorts of scrap metal—collections were held regularly to gather in these vital materials. Ration books were issued to families, and stamps were required in order to purchase rationed commodities. We saved bacon grease in tin cans and could trade it in to the butcher for an extra ration of meat. People were encouraged to economize by all possible means—nothing was to be wasted. We had meatless Tuesdays and Fridays, and “victory gardens” grew everywhere.

Although the United States was fighting against what it saw as totalitarian regimes, the level of control that the government exercised over the American people was nevertheless astounding. The War Department had a motion picture section that was designed to influence what filmmakers could put on the screen that might affect the war effort. In those pre-television days, people got their visual news from newsreels in movie theaters preceding the main attraction. Patriotic messages were inserted into commercial films at the request of the Pentagon; film producers were glad to oblige. At the direction of the government, newsreels were not to show any pictures of American battlefield casualties until late in 1943. If those restrictions can be seen as thought control, the American people generally understood that it was for a good cause.

Huge rallies were held in theaters and parks for the sale of war bonds. Patriotic announcements in movie theaters preceded most films, asking people not to discuss troop movements; to buy war bonds; and to give moral support their fathers, sons, and husbands who were serving overseas. It was even considered unpatriotic for a woman to end a romantic relationship with a soldier overseas lest it damage his morale. A popular song written with servicemen in mind proclaimed that their women were being “good as gold” because all the men back home were “either too young or too old.” As schoolchildren we purchased savings stamps with our quarters, and when we had $18.75 pasted into our books, we took them to the bank or post office and turned them in for a $25 war bond.

Cartoons of Hitler, Tojo, and Mussolini were commonly seen alongside patriotic posters proclaiming that “Uncle Sam wants you!” It was a total war, and the entire population was involved. Because of the huge demand for workers in automobile, steel, and other plants that were vital to the war effort, workers in those industries were exempt from the draft. For a time the government contemplated drafting men to go to work in factories in war-related industries, but abandoned the idea because it might be a violation of civil rights.

American Industry at War

Historians have pointed out that World War II was won not only on the battlefields of North Africa, Europe, the Pacific Islands, and Asia, but that it was also won in Pittsburgh, Detroit, Birmingham, St. Louis, on the West Coast, and in all the other areas where the war industries were congregated. Beginning in the spring of 1942, factories ran twenty-four hours a day, six or seven days a week. Unemployment during the war dropped to slightly more than 1 percent of the working age population. Government spending during World War II in inflation adjusted (2008) dollars was 4.1 trillion dollars. The cost of all prior wars combined was 325 billion dollars. In actual dollars it federal expenditures during the war were twice as much as was spent in all of American history to that point put together. By 1944 almost 90 percent of government spending went to the war cause.

The absence of men from the workforce and the demands of a wartime economy drew millions of women into paying jobs outside the home. Six million more women were working at the end of the war than at the beginning. Although resentment from male workers existed, over time as women proved themselves, and as the demands of war grew, such attitudes became rare. Government encouraged women to get into defense work by claiming, for example, that if a woman could use a sewing machine, she could operate a drill press. Women were soon at work building tanks, ships, guns, airplanes and other military equipment. “Rosie the Riveter” became an icon for female labor power. Although sex discrimination on jobs returned after the war, the expanding roles for women during the war were a source of inspiration in the later women’s liberation movement.

Between 1942 and 1945 the production of consumer goods slowed to a trickle, as the Singer Sewing Machine Company made machine guns, and Ford and General Motors made trucks, tanks, and armored vehicles. Goods such as washing machines and other appliances were in short supply. Between 1942 and 1945 hardly any new civilian automobiles were built as the motor companies worked around the clock to turn out military vehicles and aircraft.

The quantity of goods and the speed with which they were produced astonished observers. The aircraft industry produced 324,750 planes during the war, with ever increasing efficiency. In 1941, production of a B-17 required 55,000 individual worker hours. By 1944 the figure was down to 19,000 hours. The Kaiser shipbuilding company turned out ships with amazing speed, and in one exercise just to prove a point, they actually constructed a vessel from the keel up in 4 days, 15 hours and 30 minutes. The ship, the SS Robert E. Peary, sailed seven days after the keel was laid.

The Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress” was one of the great aircraft of World War II. With a crew of ten, the B-17G—one of the later models—could fly at up 300 miles per hour at 30,000 feet, carrying a bomb load of 8,000 pounds over a range of 1,850 miles. The aircraft could defend itself with thirteen .50-caliber machine guns, but bomber squadrons were generally accompanied by fighters for additional protection.

While the stout B-17 airplane could sustain considerable damage and keep on flying, more than 4,000 were lost from enemy action and other causes such as accidents in the European theater alone. One raid on Schweinfurt, Germany, in 1943 resulted in 60 bombers lost and 30 more damaged beyond repair. The highly trained crews were as hard to replace as lost aircraft, especially given the policy that after twenty-five missions over enemy territory, airmen would return to the States to train others.

Although there were those who profiteered from those sorts of things, and although a black market existed (a grocer in our village was happy to provide an extra ration of meat in exchange for a few extra dollars), most Americans simply accepted things as they were. Since silk and nylon had disappeared from stores—they were going into parachutes—women put makeup on their legs and traced with an eyebrow pencil what was meant to look like a seam on the back of their “stockings.”

Such was the devotion of the American people toward the war cause that one phrase frequently uttered when some thoughtless person was observed doing something not in the best interest of the country was: “Don’t you know there’s a war on?!” It was everybody’s war. If a family existed that wasn’t touched in some way or other by the enormous effort put forth to win World War II, that family was probably very isolated from the rest of American society.

Internment of Japanese Americans. The fear and anger generated by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor led to one of the sorriest episodes in American history. Although there was no call for instant retribution against Japanese Americans in the weeks immediately following the attack, continued Japanese advances and victories raised fears on the West Coast that the Japanese might attempt an attack on the American mainland. In Hawaii, where approximately half of the population were Japanese, any attempt to exert mass controls over the Japanese population would have been impossible. Individual arrests were made in Hawaii, however, of persons suspected of actual espionage activity.

On the West Coast of the United States, however, the situation was different in that the population of Japanese-Americans, whether immigrant or foreign-born, was approximately 120,000, a much smaller percentage of the total population than was the case in Hawaii. Occasional reports of enemy aircraft or submarines off the California coast helped to generate fear and suspicion of the Japanese population. Because the West Coast was considered vulnerable to attack, responsibility for the security of the Western states was turned over to the Army.

On the West Coast of the United States, however, the situation was different in that the population of Japanese-Americans, whether immigrant or foreign-born, was approximately 120,000, a much smaller percentage of the total population than was the case in Hawaii. Occasional reports of enemy aircraft or submarines off the California coast helped to generate fear and suspicion of the Japanese population. Because the West Coast was considered vulnerable to attack, responsibility for the security of the Western states was turned over to the Army.

Amid fears that espionage against the U.S. might be carried out, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The Order authorized commanders of military areas to exclude “any or all persons” from designated areas. Attorney General Francis Biddle and others vehemently opposed the detention of Japanese Americans, but pressure from editorials, California officials, including Governor Earl Warren, spread rapidly. General John L. DeWitt, Commander of the Western District, reported that radio signals were being transmitted from the West Coast to inform Japanese submarines of American ship movements. (See David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, 748-760.)

The FBI and other intelligence agencies determined that reports of suspected espionage activities were false, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who opposed the internment of Japanese Americans, wrote to Attorney General Biddle that all reports had been investigated, “but in no case has any information been obtained which would substantiate the allegation." General DeWitt, who had initially opposed relocation of the Japanese, nevertheless initiated the order to remove all Japanese from the West Coast. Although Secretary of War Stimson recognized that the rights of some loyal citizens would be violated, he authorized the operation.

Thousands of Japanese were loaded onto buses and railroad trains and moved to internment camps or relocation centers throughout the Western states. They were permitted to take only a few belongings, and the departures were wrenching, as looters frequently pillaged Japanese homes and businesses even as the owners were leaving. Japanese who wish to were allowed to leave the West Coast voluntarily, and some 15,000 went to live with friends or relatives in other parts of the country.

Although their existence in the camps did not involve overt forms of harassment or harsh treatment, the Japanese, including many native-born American citizens, were nevertheless imprisoned. Conditions in the camps varied from wretched to tolerable. To Japanese printed newspapers and created a normal facilities like schools, fire and police departments. The internees were permitted to farm in the area surrounding the camps. As the war progressed, young Japanese men and women were permitted to join the Army. In the course of the war over 20,000 Japanese American men and women served in the U.S. Army. One group of Japanese soldiers comprised the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team. They fought in Europe and were one of the most highly decorated American units in the war.

In 1944 the Supreme Court ruled on the issue of Japanese in the case of Korematsu v. United States. Fred Korematsu refused to obey Executive Order 9066; He was arrested, tried, and convicted and appealed his case to the Supreme Court on the grounds that the Order was unconstitutional. The Court upheld the order by a vote of 6-3, stating that Korematsu was excluded from the restricted area “because we are at war with the Japanese Empire.” Under the circumstances, the Court said, the military had the right to take what they considered necessary precautions. Justice Frank Murphy dissented from the majority decision. He called the exclusion of Japanese comparable to Germany's racist policies. He said, "I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life."

In 1944 the Supreme Court ruled on the issue of Japanese in the case of Korematsu v. United States. Fred Korematsu refused to obey Executive Order 9066; He was arrested, tried, and convicted and appealed his case to the Supreme Court on the grounds that the Order was unconstitutional. The Court upheld the order by a vote of 6-3, stating that Korematsu was excluded from the restricted area “because we are at war with the Japanese Empire.” Under the circumstances, the Court said, the military had the right to take what they considered necessary precautions. Justice Frank Murphy dissented from the majority decision. He called the exclusion of Japanese comparable to Germany's racist policies. He said, "I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life."

The internment ended in January 1945, although the war was still on. Fred Korematsu’s conviction was eventually overturned. In 1988 and 1992 civil liberties acts were signed by Presidents Reagan and George W. Bush awarding the survivors compensation for their losses for a total on 1.6 billion dollars. Both presidents issued formal apologies to Japanese Americans. The Manzanar Camp in California, the best known of the camps, is now a historic landmark and museum.

An excellent 1990 film, “Come See The Paradise,” starring Tamlyn Tomita and Dennis Quaid, directed by Alan Parker, tells the story of a Japanese family who were moved to an internment camp.

Science and World War II

For those of you who may have had relatives in World War II, or those who have heard stories about the bravery of our soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen, you no doubt think of them as heroes. If you are familiar with Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation or have seen Saving Private Ryan or one of the many other films about World War II, you have probably been impressed by the contributions of all those brave American men and women who served our country in time of peril. Over 400,000 of them gave their lives for the cause.

There are other stories, however, and in terms of the outcome of the war, they may have been just as important, though far less glamorous, as the deeds of the men in battle. One such story is told about the ingenuity of soldiers on the battlefield who were able to overcome obstacles through their own background knowledge and inventiveness. Countless American soldiers had been automobile mechanics, construction workers, electricians, engineers, and practitioners of many other such occupations. From time to time they were able to solve problems in combat that helped defeat the enemy. One famous example is that of an engineer who rigged up a device made of scrap metal from the Normandy beaches to help tanks get through the muddy irrigation fields and ditches in northwestern France, as was mentioned earlier.

There are other stories, however, and in terms of the outcome of the war, they may have been just as important, though far less glamorous, as the deeds of the men in battle. One such story is told about the ingenuity of soldiers on the battlefield who were able to overcome obstacles through their own background knowledge and inventiveness. Countless American soldiers had been automobile mechanics, construction workers, electricians, engineers, and practitioners of many other such occupations. From time to time they were able to solve problems in combat that helped defeat the enemy. One famous example is that of an engineer who rigged up a device made of scrap metal from the Normandy beaches to help tanks get through the muddy irrigation fields and ditches in northwestern France, as was mentioned earlier.

Another story is that of a group of men who rarely if ever saw a battlefield. They were the scientists in the university laboratories and research departments of large corporations who solved hundreds of technical problems that led to the creation of weapons and other tools that served American fighting men on land, at sea and in the air. One such group worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop a variety of radar systems that spelled the difference between success and failure in the skies over Europe and the Pacific. One such radar device enabled British technicians to locate and defeat hundreds of the V weapons, known as “buzz bombs,” that Hitler sent over the British Isles in hopes of killing thousands of British civilians and bringing Great Britain to her knees.

Other radar devices helped pilots locate targets for their bombing missions, up to and including the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan. Still others aided crippled aircraft, or bombers with wounded flight crews, to find their way back to a safe landing field. By the end of the war such devices were able to land planes even if the pilots could not see the field . (Many such devices, of course, found invaluable applications in civil aviation in the years following the war.)

The story of the creation of the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico, has been told many times by observers and participants, and numerous films have illustrated the story as well. Biographies of men like J. Robert Oppenheimer have chronicled the heroic efforts of the scientists who worked feverishly to bring the weapon to completion in time to help the war effort. Although controversy still surrounds the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the consensus view is that they ended the war.

Far less well-known is the story of a man named Alfred J. Loomis, a millionaire scientist who built his own private laboratory at Tuxedo Park, New York. During the war he helped put together the team of scientists at MIT who created the radar devices that truly can be said to have won the war. The vast radar network upon which aviation safety depends has its roots in wartime radar development.

As mentioned above, nothing can detract from the heroism and bravery of the American fighting men and women who faced incredible challenges to defeat two determined and well-equipped enemies. Yet without the tools of combat provided to them by American scientists and engineers, their job would have been far more difficult if not impossible.

Presiding over that monumental effort of marrying military skill with scientific knowhow was Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, one of the most remarkable political figures in American history. He began his career as United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York under Theodore Roosevelt and served as Secretary of War under President Taft. Over the next 30 years he held various other important posts, including the position of Secretary of State under President Herbert Hoover. As the threat of war neared in 1940 President Franklin Roosevelt named him once again Secretary of War, a post in which he served with great distinction until his retirement in 1945.

“If Hitler invaded hell, I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.” —Sir Winston Churchill

The combined military might of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and the militarist Japanese Empire required a high-level of cooperation among the powers fighting against the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis. Among the major powers, the United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China conducted a series of high-level meetings to establish the overall policies and strategies for the conduct of the war.

The meetings began in 1941 when Prime Minister Churchill and President Franklin Roosevelt met on the British warship Prince of Wales in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland. The two leaders quickly established a rapport and agreed on broad war aims such as self-determination of all people in their governments, free trade, fair labor and economic policies, and permanent peace arrangements guaranteeing freedom of travel on the high seas. The goals were not unlike Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, not surprising as Roosevelt had spent eight years in the Wilson government.

Following Pearl Harbor Churchill and Roosevelt conferred regularly. Churchill made frequent visits to the White House where he and the president would spend days conferring about policy while the American and British and joint staffs worked on details.

By early 1943 it was necessary to refine the major goals for the war. President Roosevelt traveled to Casablanca, Morocco, where he met with Prime Minister Churchill and Charles de Gaulle of France. Perhaps the most important decision regarding war objectives was reached at Casablanca when the Allies decided to insist upon an unconditional surrender by the Axis powers. They further agreed that the next step in the assault on Germany would be the invasion of Sicily and Italy, and they agreed to assist the Soviet Union by all possible means.

In November 1943 the president traveled again, this time to Cairo, where he met with Prime Minister Churchill and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China. In Cairo the three leaders reaffirmed their decision to continue to apply military force to Japan until Japan surrendered unconditionally. They also agreed that Japan was to return all occupied territories gained from World War I and that Korea should become free and independent. Following the Cairo conference the president moved on to Teheran, Iran, with Prime Minister Churchill where they met with Josef Stalin. At the Teheran conference the major topic of discussion was the strategy for achieving the final defeat of Nazi Germany and the opening of the second front in Europe, for which Stalin continued to push vigorously. The Big Three also promised economic assistance to Iran.

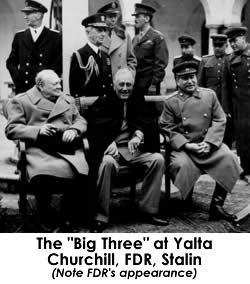

The next major big three conference took place at Yalta in the Crimea in February 1945. By that time Roosevelt’s health was failing, and the long trip put him under considerable strain. It was clear to the gentlemen gathered in Yalta that the war against Germany was nearing a successful conclusion, so postwar issues rose to the fore. Premier Stalin wanted to establish a Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe whereas Churchill and Roosevelt pushed for free and democratic elections in that part of the world. Fear of the spread of Communism in the postwar world lay behind the concerns of Churchill and Roosevelt.

The next major big three conference took place at Yalta in the Crimea in February 1945. By that time Roosevelt’s health was failing, and the long trip put him under considerable strain. It was clear to the gentlemen gathered in Yalta that the war against Germany was nearing a successful conclusion, so postwar issues rose to the fore. Premier Stalin wanted to establish a Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe whereas Churchill and Roosevelt pushed for free and democratic elections in that part of the world. Fear of the spread of Communism in the postwar world lay behind the concerns of Churchill and Roosevelt.

Stalin made it clear that he would control Poland because it had historically served as a corridor for attacks against Russia. Roosevelt pushed Stalin to agree to enter the war against Japan once Germany was subdued, and he also urged the Soviet premier to join the United Nations. There was talk of free elections in Eastern Europe, and Stalin did sign an agreement on that general topic, but it was only a statement of principle.

The decisions and agreements made at Yalta remained controversial for years afterward, and much was blamed on FDR’s poor health. Roosevelt does seem to have been too willing to believe that Stalin was a reasonable man who wanted peace, but it is unlikely that a hard line in Yalta would have produced significantly different results in the long run.

The final wartime meeting took place at Potsdam outside Berlin in July 1945 after Germany had capitulated. Winston Churchill was replaced by Clement Attlee, the newly elected British prime minister, during the conference. At Potsdam President Harry Truman informed Premier Stalin of a powerful new weapon, the atomic bomb, about which Stalin was already informed. Stalin confirmed his commitment to enter the war against Japan within three months of Germany’s surrender, which reassured Truman. There is speculation that the decision to drop the atomic bomb was aided by the hope that by preventing an invasion of Japan, Russia could be kept out of that country, thereby limiting Communist expansion in Asia. Available evidence, however, makes that claim doubtful.

This very brief overview of the wartime conferences only suggests the complexity of the diplomatic efforts put forth by all parties. Many additional meetings between top and high-level officials took place throughout the war, and a wide range of difficult issues had to be dealt with. It can be stated with reasonable certainty that the overriding goal of defeating Germany and Japan was never lost from sight. Most of the controversy arose over the disposition of the warring nations once the piece had been secured.

SUMMARY & Legacy of WORLD WAR II

Woodrow Wilson’s dream of making the world safe for democracy through a war to end all wars did not come true in his time. From our vantage point in the 21st century we might look back at the end of the Cold War in 1990 and think that perhaps we were moving in that direction, and that Wilson’s dream might have become a reality. Now in the early years of the 21st century we know that wars can take on a different character and are fought in many different ways.

As we have said above, World War II, the “Good War,” was in many ways an extension of World War I, the “Great War.” Although it may not have been the last war, it did apparently bring an end to the kind of war that had plagued humanity for centuries: territorial wars fought among the major powers of the world for land and empire. The chance of a major nation declaring war on its neighbor in our century seems remote at this writing.

Perhaps the reason for that goes back to something General Robert E. Lee said during the Battle of Fredericksburg: “It is well that war is so terrible, else we should grow too fond of it.” General Douglas MacArthur, who certainly saw his share of warfare, gave voice to a similar sentiment when contemplating the significance of the arrival of atomic warfare, which he claimed would end war as we knew it at the time. Perhaps it was the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that finally brought the world to the realization that all-out war now had the capacity to destroy the world as we know it.

After the First World War, the United States was able to retreat into a position of quasi-isolationism. Following World War II such a retreat was never an option. As the U.S. was the world’s first superpower and only atomic power, soon to be joined by the Soviet Union, the post-World War II world evolved into a condition described as the “balance of terror.” I can recall sitting in a history lecture in the late 1950s where the professor assumed that there would be a world war three, but warned us to watch out for the Germans in world war four. A more cynical commentary on the situation went, “I don’t know what they’ll use for weapons in world war three, but in world war four they’ll be using spears.”

The United States, the only major nation virtually untouched by the Second World War on its own territory, quickly converted its war-making industries to civilian uses. This situation generated an economic boom that was unprecedented in any nation’s history. Having seen itself as a rescuer of the free world in the two great wars, however, the United States, perhaps too easily, assumed the role of the world’s protector. Whether the adoption of that role was driven by true compassion for our fellow citizens, or by what has been described as the “arrogance of power,” is still being debated. What is clear is that World War II was once and for all the end of innocence. The casualties of World War II are literally incalculable. The number of deaths is estimated at 50 to 60 million from all causes, and the number of homeless, displaced persons also numbered in the millions. The economic costs can only be guessed at. It took years for the world to recover, and in some ways, the recovery is still not complete.

The Legacy

World War II changed life on earth more than any other man-made event in history. The horror is almost incalculable: 50 million people died. It is impossible to estimate with any accuracy the total value of all property damaged or resources consumed to produce the articles of war. In the United States production of many important products, from sewing machines to automobiles, was suspended in order to build machine guns, tanks, and warplanes.

Besides those killed in combat, millions more fell victim to starvation and other ills; tens of millions were displaced, their homes and the cities and villages in which they lived having been totally demolished. Refugees wandered for years, and the term "displaced persons" came into regular usage. In the town where I grew up, refugees from Poland and other European countries arrived, and it was clear from the behavior of the young people who joined us in our schools that they had suffered in ways that to us were unimaginable. Those I remember seem to have been hard, joyless, mature far beyond their age—they had been forced to grow up too soon.

There was talk in some quarters of reducing Germany to an agricultural nation that would never be able to manufacture war materials in quantity again. General Douglas MacArthur, sometimes referred to as "an American Caesar," oversaw the creation of a new form of government in Japan, including a Constitution that outlawed war except for strictly defensive purposes. The struggle in China between the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist followers of Mao Tse Tung continued for years beyond the war. In both Europe and Asia governing officials of Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany had to be used to administer the normal daily needs of millions of people. In countries such as Korea, that created problems that took years to resolve.

World War II saw the dawn of the nuclear age. Thanks to working for the Soviet Union in Great Britain and the United States, Russian scientists soon developed a bomb in the nuclear arms race was born. The United States and the nations of Western Europe formed the NATO as a means of enhancing collective defense. The United Nations began to function as a body, one of whose goals was the prevention of further war. And although a total war of the magnitude of the first and second world wars has been avoided, United Nations cannot be said to have prevented warfare anything nearly completely.

Below are the words uttered by General Douglas MacArthur at the ceremony in Tokyo Bay that brought World War II to a final conclusion.

The “Greatest Generation”

When Americans talk about the greatest generation, they are referring to men and women born in the last decades of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th. This is the generation that fought the Second World War. Whether they were made of better stuff than the patriots who took on the most powerful empire in the world in 1775, or the boys in blue and gray who fought in America’s bloodiest conflict from 1861 to 1865, can well be argued. But their accomplishments are unquestioned.

When news of Pearl Harbor spread across the country, thousands of young men walked off their jobs and headed for the nearest recruiting office. They came from all walks and conditions of life, and they were in it for the duration. Unlike other wars fought since the Second World War, the notion of rotation in and out of combat with periods of leave at home was unknown. When they shipped out in 1942 and 1943, they had no idea when or if they would see American soil again.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall adopted a very straightforward policy. Once units were constituted for combat, they would continue to exist, as replacements were sent to the front lines to take the place of those who had been killed and wounded. The value of having experienced men in virtually every front-line unit by the time Europe was invaded in 1944 certainly paid off, but the price was terribly high. The casualty rate in front-line infantry units was 100%; that did not mean, of course, that everyone in a unit might be killed. What it meant was that over their duration of the war, the number of casualties in any given unit would at least equal the number of men in that unit at full strength. A soldier who fought from North Africa to Italy, thence to Normandy and across the Rhine was a lucky man indeed. (See Forrest C. Pogue, George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory 1943-1945, New York: Viking, 1973.)

When the fighting was over in Europe, soldiers who had conquered the Germans and Italians were scheduled to be shipped straight to the Pacific to wrap up the war against the Japanese. The planned invasion of the Japanese homelands, which was made unnecessary by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, meant that few soldiers who fought in Europe ever saw action against Japan. But they were prepared to go.

One personal story may illustrate the dedication of that “greatest generation.” Staff Sergeant Donald H. Sage, Jr., was a bombardier in the Army Air Corps flying in B-25 bombers over “the hump” to support American troops fighting alongside the Chinese against Japan. Staff Sergeant Sage had been accepted for officer training and flight school. Having completed his 25 required combat missions, he was eligible to return to the states for training. As he was preparing to depart, however, an urgent request for air support came in from front-line troops serving under General Stillwell in China. Although not obligated to fly any further combat sorties, Staff Sergeant Sage volunteered for the mission. He did not return from the mission. He was awarded the Bronze Star Medal posthumously by President Truman in 1945.

Thousands of Americans made comparable sacrifices during the period of America’s fighting during World War II.

| World War II Home | Updated April 28, 2017 |