Colonial Life: Faith, Family, Work

Colonial life was hard. Whether you were a colonist in New England, where winter blasts brought cold, sleet and snow, or in the southern colonies, where oppressive heat and mosquitoes made the summers torturous, or anywhere in between, life was challenging, especially in the earlier decades of colonization. Everybody had to be productive for families to survive. Men and women, even in their separate spheres, had to work hard to support life. Conflicts with Indians could threaten life and limb, and on the edge of the frontier, other dangers lurked. Although colonial life could be healthier than in the teeming cities of Europe, colonists were exposed to diseases they had not encountered in the old countries. Nevertheless, though thousands died, thousands more prospered.

These were hardy folk who had risked everything to cross the ocean and embark on a new life, or they were descendants of those who had. With a little luck, they would become landowners, growing wheat, barley, and the newly discovered corn, while raising cattle, pigs and chickens. They had little chance of becoming wealthy, but they were able to keep from starving. Families grew stronger, and neighbors help one another. While not necessarily welcomed with open arms, newcomers were brought into the fold as extra hands who could help the community grow with whatever labor they were fit to perform. As people of faith, most believed in some kind of God; with work always left to be done, however, Sunday's would be more likely to find them in the fields than in a church. They saw few miracles, and they believed in the notion that God helps those who help themselves.

The Protestant Reformation in Germany and England

In order to fully understand American history one must have a grasp of the role that religion has played in the development of this nation. In fact, the history of religion in the Western world going back hundreds of years before the discovery of America has affected this nation to the present time. The origins of much of our religious heritage can be traced to the major upheaval in western religion that began in the 16th century with the Reformation. The dominant theme in the history of religion in the Western world has been the conflict between different faiths: Christianity and Judaism; Christianity and Islam; Catholicism and Protestantism. It is the last of those conflicts, the struggle between Catholics and Protestants, that dominates colonial American history. Although we like to think of religion in government as separate realms, politics and religion have always been intertwined. Even the creation of what we now call the Roman Catholic Church under the Emperor Constantine was done with political considerations in mind. For centuries the church was instrumental in the affairs of governments and Kings. The Pope in Rome depended on the support of secular rulers, and those rulers depended upon the moral support of the Vatican for their legitimacy. The "divine right of kings" depended on the constancy of religious leaders in support of that allegedly God-given right. Thus it was inevitable that when the Christian world, which in an earlier time had separated into Eastern and Western branches, became divided between Catholic and Protestant faiths, political matters would become embroiled with religious issues.

In the early 1500s, Martin Luther, a German priest, became scandalized by the degree of corruption he observed in the Catholic Church. Today we refer to Luther’s church as the Roman Catholic Church, but at that time it was the only church that existed in the Western world, although Catholicism varied in certain ways from country to country. For all kinds of reasons stemming from the church having wielded extraordinary social and political pressure over the Western world for more than a thousand years, the corruption in the church touched the lives of many people. Luther was an extremely pious and devout priest, so much so that even on the day of his ordination, he was not confident that he was holy enough to be able to conduct his first mass. It is understandable that a man with serious concerns about his own holiness would be shocked to discover corruption in an institution he revered.

In the early 1500s, Martin Luther, a German priest, became scandalized by the degree of corruption he observed in the Catholic Church. Today we refer to Luther’s church as the Roman Catholic Church, but at that time it was the only church that existed in the Western world, although Catholicism varied in certain ways from country to country. For all kinds of reasons stemming from the church having wielded extraordinary social and political pressure over the Western world for more than a thousand years, the corruption in the church touched the lives of many people. Luther was an extremely pious and devout priest, so much so that even on the day of his ordination, he was not confident that he was holy enough to be able to conduct his first mass. It is understandable that a man with serious concerns about his own holiness would be shocked to discover corruption in an institution he revered.

Luther began to collect his complaints and finally delivered them in the form of ninety-five theses that he nailed on the door of the cathedral in Wittenberg, Germany. To say that his complaints were timely doesn’t quite capture the impact; within one generation of Martin Luther’s protest, Protestantism, consisting of a number of Christian sects that had rebelled against the leadership of the Roman authorities, had spread over much of northern Europe. As frequently happens in cases of such revolution, after the initial revolution was complete, it fragmented further into various segments. Thus the Protestant Reformation led to the creation of a variety of churches: Lutheran, Baptist, Methodist, Calvinist, and many other varieties. (More than one hundred different Protestant denominations exist in America today.) The political implications of the Protestant Reformation soon emerged, as the Roman Catholic church was deeply embroiled in matters of government throughout the European world.

Most interesting for American history is the fact that at the time the Reformation was beginning, a young English prince had fallen in love with his brother’s widow; he was Prince Henry, she was Catherine of Aragon. At that time it was considered incestuous for a man to marry his brother’s widow, so Henry appealed to the Rome to nullify the marriage between his brother Arthur and Catherine so that he would be free to marry her. The Pope in Rome, nervous over the fragmentation of his religious domain, was happy to grant an annulment to keep the English monarch in good favor. The prince became King Henry VIII, and his story is well known. What is not so well known is that several years into his reign Henry argued forcefully against the reforms of Martin Luther and defended the Roman church from what he saw as false accusations. In recognition of his faithful service, he was named “Defender of the Faith” by the Pope, a title borne by British monarchs to this day.

The story does not end there, of course. After twenty years of marriage to Catherine of Aragon, with no male heir to show for it, Henry became disenchanted with his wife. At the same time he was becoming attracted to a handsome young woman of the court, Anne Boleyn. The story of Henry’s infatuation with Anne is less important than the fact that eventually he sought an annulment from Catherine on the grounds that the original annulment had been against God’s favor. He claimed to believe that the reason he had no male heirs was because God was displeased with his marriage to Catherine. Now the pope was in a very difficult position; he was being asked to declare that the daughter of two powerful Catholic monarchs of Aragon and Castile, which eventually became the kingdom of Spain, had been living in sin with the English king for decades, and that their child, a girl named Mary, was a bastard. In addition, Catherine’s nephew was the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, a powerful political figure and staunch supporter of the Catholic Church, who would also have been outraged by the annulment. So the pope denied Henry’s request.

The story does not end there, of course. After twenty years of marriage to Catherine of Aragon, with no male heir to show for it, Henry became disenchanted with his wife. At the same time he was becoming attracted to a handsome young woman of the court, Anne Boleyn. The story of Henry’s infatuation with Anne is less important than the fact that eventually he sought an annulment from Catherine on the grounds that the original annulment had been against God’s favor. He claimed to believe that the reason he had no male heirs was because God was displeased with his marriage to Catherine. Now the pope was in a very difficult position; he was being asked to declare that the daughter of two powerful Catholic monarchs of Aragon and Castile, which eventually became the kingdom of Spain, had been living in sin with the English king for decades, and that their child, a girl named Mary, was a bastard. In addition, Catherine’s nephew was the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, a powerful political figure and staunch supporter of the Catholic Church, who would also have been outraged by the annulment. So the pope denied Henry’s request.

Infuriated and infatuated, Henry decided to break with Rome, and thus came about the English Reformation, so-called because Henry made himself head of the Church of England, which became known as the Anglican Church. Although the Anglican Church had formally severed its ties with Rome, the Anglican faith kept many of the trappings of what was now known as the Roman Catholic religion. Many Protestants, who felt that Martin Luther had not gone far enough in his reforms, objected to the continuing “remnants of popery” that emanated from English cathedrals and demanded that the church be further purified of Catholic influence. The most vociferous of these were known as Puritans, who divided themselves into two camps, Puritans and Separatists.

The Puritans were those who stayed in England during the reign of Henry’s heirs, especially during that of Queen Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry and Anne Boleyn. They tried to work within the system to help reform the Anglican Church. They were willing to conform to the political demands of the church, for church and state were one, because the king was head of both. The Separatists, however, being more radical, were unwilling to continue to live under the domination of the church and sought their salvation elsewhere. The Separatists eventually became the Pilgrims who settled in Plymouth in 1620, and the Puritans were the great mass of people who came to America’s shores in Massachusetts Bay, beginning in 1630. The influence of the Puritans and the Anglican faith and many other religious convictions that colonial Britons brought with them from England and other countries has become part of the legacy of American religious history.

We should keep in mind here that conflict between Catholics and Protestants has persisted into modern times. Even now in the 21st century, some religious leaders continue to claim that the Catholic Church is corrupt, even to the point of asserting that the Pope himself is the Antichrist. (Not long ago I happened to be taking some relatives through Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol. We were standing in front of the statue of Father Jacques Marquette, known as Père Marquette, one of the founders of what became the state of Michigan. Marquette's Catholic faith was evident from the rosary beads in the statue. As we stood there, a young many behind us said in an outraged tone, "Do they even let Catholics in here?!")

Religious Freedom

The quest for religious freedom is often stated as a motivating factor in the colonization of North America, but its exact nature is often misunderstood. Our concept of religious freedom today means that people of all faiths Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, or any other, including those who lack faith, should be free to follow their own religious inclinations without interference from others and especially not from the government. During a time of colonization England and the rest of Europe were in the throes of monumental religious controversies. The religious tension was more than just Catholic and Protestant; Puritans, Presbyterians, Quakers, Methodists, Baptists and others all had their own particular forms of worship and systems of belief. People who came to America in the 17th and 18th centuries were not seeking land of religious freedom for all so much as a land where they could practice their own form of religion free of interference from rival denominations.

One overriding theme of religion in colonial America was hatred of everything Catholic. Thousands of people died in Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe during the struggles between Catholics and Protestants, beginning with King Henry VIII’s replacement of Catholic Rome with his own Anglican structure, a conversion that was later rejected by his daughter Queen Mary, who clung tenaciously to her Catholic faith. When Henry died, another claimant to the throne, Lady Jane Grey, assumed the crown for a brief period. A staunch Protestant, Jane was removed in favor of Mary after nine days and was later executed because of her faith. When the Protestant Elizabeth came to the throne, she was constantly advised to be wary of Catholic suitors for her hand as well as Catholic threats to English sovereignty. When her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, a Catholic, was implicated in a plot to overthrow Queen Elizabeth and replace her with Mary, Mary was tried and found guilty of treason. Elizabeth signed her execution order, and she was beheaded. During Elizabeth's reign, her counselors were constantly aware of threats to the person of Elizabeth because of her Protestant faith.

That religious tension was carried into the colonies, as much of British colonial policy—such as it was—was directed against Spain. Catholic Maryland was an exception to the religious exclusionism, but even there problems existed, as tension existed between Maryland and surrounding colonies. The famous Maryland act of religious toleration passed in 1649 was repealed before very long.

The religious origins of American colonization are very deep and are also part of the larger history of Christianity in the Western world. The Crusades of the Middle Ages are part of that story, for they helped to inspire the desire for exploration and contact with the Near and Far East. The Crusades also contributed indirectly to the forces that led to the Reformation, and such religious practices as the prosecution of witches, fear and oppression of heretics, and various other negative—as well as many positive—religious impulses were transmitted by the colonists across the seas.

The Protestant Reformation itself, begun by Martin Luther, is probably the single largest event that impacted on Europe and therefore on its colonies in modern times. The Reformation set off, among other things, a shattering conflict between the Roman Catholic Church and the different Protestant groups, a conflict that was often played out on bloody battlefields between nations that adhered to the Roman faith and those that had broken away. Lesser conflicts, such as those that continue to plague such places as Northern Ireland, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, are further dimensions of that great religious struggle that has been going on for four hundred years or more. The troubles to which the Reformation gave birth played a direct role in the colonization of America, most notably in the desire of English Puritans to escape what they saw as intolerable conditions in England. That struggle in turn had its root in the English Reformation, by which King Henry VIII separated the English church from Rome. By that time Protestantism itself had further subdivided into different sects and churches, and much of the religious disharmony in the early modern period occurred among Protestant sects as well as between Protestants and Catholics.

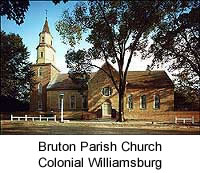

Americans to this day are inheritors of traditions and ideals passed down from the early Puritan settlers. Early in this century the German sociologist Max Weber wrote a book called The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Under various rubrics—the Yankee work ethic, for example—those ideas of Weber’s are still with us, and they have their origins in Puritan New England. From the Congregational religion, the Puritans also contributed to our political structure, initiating what became the “New England town meeting,” a still viable form of direct democracy. That localized means of government, whose origins were religious, helped define the way localities in that part of the country are governed to this day. Similarly, in the southern colonies, where the Anglican Church was dominant, the county, or parish, was the basic structure of church rule and therefore also of political rule. Government by county instead of by township or village is still the norm in much of the South.

Perhaps the most important legacy of religious attitudes that developed in colonial America was the desire of the colonists not to let religious differences infect the political process as had for so long been the case in Europe. Thus our First Amendment to the Constitution may be traced to colonial times as part of the religious legacy of that era.

The Role of Religion

To say that religion played a large role in American history is an understatement. The section you have read on the Reformation in Germany and England (above) should have led you to understand that religion was an important factor in bringing early colonists to America. Whether they were Puritans escaping what they saw as Anglican persecution, Anglicans settling for the glory of God and country, German pietists, Dutch reformers, Quakers, Catholics or whatever brand of Christianity they practiced, many early colonists came here for religious purposes, and they brought their religious attitudes with them.

The varieties of religious experience in the colonies were widespread: Puritans in Massachusetts, who practiced the Congregational religion and made it part of their political structure; Quakers in Pennsylvania, whose faith influenced the way they treated Indians, and who issued the first formal criticism of slavery in America; Catholics in Maryland, who passed a law of religious toleration, only to repeal it when religious conflict sharpened. All colonies had strong religious values and strict practices; even Virginia Anglicans accepted readily the notion that the state should support the established religion. A part of the taxes Virginians paid went to the parish to pay Anglican ministers and other church personnel.

The varieties of religious experience in the colonies were widespread: Puritans in Massachusetts, who practiced the Congregational religion and made it part of their political structure; Quakers in Pennsylvania, whose faith influenced the way they treated Indians, and who issued the first formal criticism of slavery in America; Catholics in Maryland, who passed a law of religious toleration, only to repeal it when religious conflict sharpened. All colonies had strong religious values and strict practices; even Virginia Anglicans accepted readily the notion that the state should support the established religion. A part of the taxes Virginians paid went to the parish to pay Anglican ministers and other church personnel.

The American colonists knew that religious wars had torn Europe apart from the time of the Reformation, including such bloody events as the Thirty Years War, the English Civil War, and the fights between Catholics and Protestants in France. All of these events convinced the colonials that if they brought their religious conflicts to America and allowed them to continue, their lives would become as full of bloody persecutions as those they had left behind. Gradually a sense of religious harmony began to emerge, and although it was interrupted from time to time in the course of American history (as when Irish Catholics began to arrive in large numbers in the 1800s), by the time of the American Revolution Americans had decided that they wanted a life free of religious strife. Just as Roger Williams, a dissenter from the Massachusetts Bay Puritan colony, argued that the state had no right to dictate religious practice to its citizens, many more leaders such as Jefferson, Madison, and others urged that a line of separation between church and state be established and made permanent, as was done in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

It would be wrong, however, to think of religion in America as a completely oppressive institution. Read, for example, the poetry of Anne Bradstreet and see how her religious faith could bear her up in time of great sorrow, such as in the poem she wrote on the burning of her house. Preachers such as Jonathan Edwards are remembered for their “fire and brimstone” sermons, and in fact the very term fire and brimstone comes from Edwards’s “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” But if you study all of Edwards carefully, including some of those thundering sermons, you will discover that Edwards ultimately carried a message of hope and salvation, arguing that in spite of our sinful natures God loves all of us.

The Great Awakening

The first truly American event during the colonial period, according to some historians, was known as the “Great Awakening,” an event that took place in the early 1700s. This was a revival kind of experience where itinerant preachers, the most famous of whom was George Whitefield, traveled around from colony to colony urging the citizens to return to their faith in God. Jonathan Edwards, mentioned above, is also a figure associated with the Great Awakening.

The Great Awakening was the first of many periods of religious enthusiasm that seem to come and go cyclically in American history. Later on we will discuss the Second Great Awakening of the 1840s, out of which emerged, among other things, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, otherwise known as Mormons.

A great controversy goes on among observers of American history as to whether God played a real role in the American Revolution and early history, or whether Americans rejected the whole idea of religion as a significant value in American society, as suggested perhaps by the First Amendment. If one searches the Internet for information about religion in America, one will find a variety of opinions, many of them quite strong. Struggles over religious belief have come down into modern times; religious fundamentalism is still a lively part of American life. The conflict between America’s concept of itself as a Christian nation and those who object to such formulations, both in the United States and in other places in the world, continues to appear on the front pages of our newspapers and magazines. So one ignores religion and its role in American history at one’s peril—its influence is profound and its effects varied, but its role has continued through the ages.

Religion and the Revolution

Although the American Revolution was not fought over religious matters, the legacy of the religious strife in the world preceding the revolution provided the impetus for the American founding fathers to see to it that religion would not become a divisive issue in the new republic. Starting with George Mason’s Virginia Bill of Rights, written in 1776, which stated that “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience,” the state of Virginia and the nation followed a policy of keeping religion and politics officially separated. With the Virginia statute on religious freedom written by Thomas Jefferson, endorsed by James Madison, and enacted in 1786, the states gradually began to remove all connections between governments and churches. (Note: Mason’s Virginia Bill of Rights formed the basis for the Declaration of Independence and parts of the Constitution.)

The First Amendment to the Constitution, which stated that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” although it did not apply originally to the several states, did nevertheless foster an atmosphere suggesting a wall between church and state. Anyone who follows current events even in the 21st century understands that religious conflicts have not disappeared from American culture. All the same, the steps taken by the founding fathers to minimize religious controversy have stood the country in good stead.

An additional note should be added here about the relationship of colonial American attitudes toward religion and the coming of the American Revolution. As discussed above, a large number of the colonists who came to America did so in order to be able to a practice their religion freely, without interference from any higher authority. As we have seen, that desire for religious independence was not a cry for universal religious freedom, although in colonies such as Pennsylvania religious diversity was not only tolerated, it was encouraged.

As the colonists became ever more independent-minded in the 1760s and 1770s, however, it could not escape many of them that the British desire to increase its dominion over the American colonies was to be done with the complicity of the Anglican Church. The Anglican Church, after all, was the Church of England, and it was supported by English law with King George at its head. Thus the state controlled religion, and the Church of England helped the state control its people. This propensity to enforce political control through religious doctrine was recognized by the colonists.

As John Adams later noted in a letter to Dr. Jedediah Morse in December 1815, the “apprehension of Episcopacy” was part of the revolutionary ideas percolating among the American colonists. He went on: “Passive obedience and non-resistance, in the most unqualified and unlimited sense, were [the church’s’] avowed principles in government, and the power of the church to decree rites and ceremonies, and the authority of the church in controversies of faith, were explicitly avowed.” Thus was the power of Parliament, and the colonists soon began to see “that parliament had no authority over them in any case whatsoever.”

With those ideas as background, Adams, Madison, Jefferson and others sought to ensure the American government would never be allowed to use religion as a device to ensure political control. Thus the separation of church and state, embedded in the Bill of Rights, was seen as yet another safeguard against tyranny.

Women & Families in Colonial America

Early life in the American colonies was hard—everyone had to pitch in to produce the necessities of life. There was little room for slackers; as John Smith decreed in the Virginia colony, “He who does not work, will not eat.” Because men outnumbered women by a significant margin in the early southern colonies, life there, especially family life, was relatively unstable. But the general premise that all colonials had to work to ensure survival meant that everyone, male and female, had to do one’s job. The work required to sustain a family in the rather bleak environments of the early colonies was demanding for all.

While the women had to sew, cook, take care of domestic animals, make many of the necessities used in the household such as soap, candles, clothing, and other necessities, the men were busy building, plowing, repairing tools, harvesting crops, hunting, fishing, and protecting the family from whatever threat might come, from wild animals to Indians. It was true that the colonists brought with them traditional attitudes about the proper status and roles of women. Women were considered to be the “weaker vessels,” not as strong physically or mentally as men and less emotionally stable. Legally they could neither vote, hold public office, nor participate in legal matters on their own behalf, and opportunities for them outside the home were frequently limited. Women were expected to defer to their husbands and be obedient to them without question. Husbands, in turn, were expected to protect their wives against all threats, even at the cost of their own lives if necessary.

It is clear that separation of labor existed in the New World—women did traditional work generally associated with females. But because labor was so valuable in colonial America, many women were able to demonstrate their worth by pursuing positions such as midwives, merchants, printers, and even doctors. In addition, because the survival of the family depended upon the contribution of every family member—including children, once they were old enough to work—women often had to step in to their husband’s roles in case of incapacitation from injury or illness. Women were commonly able to contribute to the labor involved in farming by attending the births of livestock, driving plow horses, and so on. Because the family was the main unit of society, and was especially strong in New England, the wife’s position within the family, while subordinate to that of her husband, nevertheless meant that through her husband she could participate in the public life of the colony. It was assumed, for example, that when a man cast a vote in any sort of election, the vote was cast on behalf of his family. If the husband were indisposed at the time of the election, wives were generally allowed to cast the family vote in his place.

Women were in short supply in the colonies, as indeed was all labor, so they tended to be more highly valued than in Europe. The wife was an essential component of the nuclear family, and without a strong and productive wife a family would struggle to survive. If a woman became a widow, for example, suitors would appear with almost unseemly haste to bid for the services of the woman through marriage. (In the Virginia colony it was bantered about that when a single man showed up with flowers at the funeral of a husband, he was more likely to be courting than mourning or offering condolences.)

Religion in Puritan New England followed congregational traditions, meaning that the church hierarchy was not as highly developed as in the Anglican and Catholic faiths. New England women tended to join the church in greater numbers than men, a phenomenon known as the “feminization” of religion, although it is not clear how that came about. In general, colonial women fared well for the times in which they lived. In any case the lead in the family practice of religion in New England was often taken by the wife. It was the mother who brought up the children to be good Christians, and the mother who often taught them to read so that they could study the Bible. Because both men and women were required to live according to God’s law, both boys and girls were taught to read the Bible.

The feminization of religion in New England set an important precedent for what later became known as “Republican motherhood” during the Revolutionary period. Because mothers were responsible for the raising of good Christian children, as the religious intensity of Puritan New England tapered off, it was the mother who was later expected to raise children who were ethically sound, and who would become good citizens. When the American Revolution shifted responsibility for the moral condition of the state from the monarch to “we, the people,” the raising of children to become good citizens became a political contribution of good “republican” mothers.

Despite the traditional restrictions on colonial women, many examples can be found indicating that women were often granted legal and economic rights and were allowed to pursue businesses; many women were more than mere housewives, and their responsibilities were important and often highly valued in colonial society. They appeared in court, conducted business, and participated in public affairs from time to time, circumstances warranting. Although women in colonial America could by no means be considered to have been held “equal” to men, they were as a rule probably as well off as women anywhere in the world, and in general probably even better off.

Although women in colonial America were subject to the same prejudices that had existed in Western culture for centuries, the nature of life in America brought about more favorable circumstances for women. Because everybody had to work, and because labor was viable in America, the presence of women was seen as a blessing or leased a necessity. Men worked hard, and the women were responsible for the raising of the children. The children in turn were expected to be productive members of the family and as soon as they were old enough they began performing various chores and tasks around the household and farm to help ease the burdens of their hard-working parents. Girls learned the chores that were traditionally a woman's lot, while boys learned how to assist their fathers in the fields and workshops. Family discipline was of necessity often strict; children who are slackers constituted a burden rather than an aid to their families. They expected to lead lives similar to those of their parents, but in a land that offered a modicum of opportunity for prosperity, such expectations were reasonable.

Life in colonial times was hard. Everyone, save for the very few wealthy persons, had to work. Most were farmers, and in colonial families both men and women, as well as girls and boys, toiled daily for most of the daylight hours. Sunday was often a day of partial rest, but animals still had to be cared for, food prepared and other field and household chores attended to. Certain hours were set aside in many families for worship or lessons for children, but hours of leisure were rare in most households and treated more as necessary pastimes than as free time. In the letter of an indentured servant you get a sense of the hardship of life, and many indentured servants worked very hard and were treated harshly. They had the advantage over slaves of knowing that there was a light at the end of the tunnel--that their indentures would eventually expire and they would be free, with perhaps something of value to show for their years of work. Gottlieb Mittelberger's

The important point to remember about working conditions in colonial America is that land was plentiful and labor was very scarce. In the old countries chronic underemployment was the norm. There were simply not enough work to go around for people who had no access to land ownership. People with farming skills could work for hire, but the work was often seasonal and otherwise unreliable. In the towns and cities unless one had a skill such as blacksmithing, printing or tannery, any work was hard to find, let alone steady work. Thousands were constantly on the verge of starvation and sought relief through such activities as petty thievery or prostitution. That was why so many were willing to take a huge risk of traveling across a wide ocean to an unknown land far away.

As a letter of Gottfried Mittelberger and the Frethorne letter demonstrate, life could be just as difficult on the other side. But there was one great difference: in America land was plentiful, and those who owned land or access to it needed workers. Labor was hard, but it was available. The possibility of land ownership was open to anyone with reasonable intelligence and willingness to labor long and hard to achieve that elusive goal, the goal it was virtually impossible for common people in most of Europe.

It is no surprise then, that when a ship with a cargo slaves landed in Virginia in 1619, they were quickly accepted and put to work. In the early days many of those slaves were treated like indentured servants, and some managed to work toward freedom and even land ownership. When the slave traders discovered a market for their products in North America, however, the influx of slaves quickly transformed the institution into one of lifelong servitude. Because many of the slaves who came to America had been captured in tribal conflict back in Africa or had already served time as slaves elsewhere in the Americas, the practices attendant to the ancient institution developed in America as they have for thousands of years. More on Slavery in the colonies.

This brief overview of life in colonial America in no way portrays the complexity and diversity of colonial life. We have already seen that the inhabitants of the colonies, while mostly English, included Dutch, German, Swedish, Scottish settlers, with a smattering of immigrants from Portugal and other European nations, including some who came from earlier settlements in the Caribbean. Colonial life on the coast in settlements slowly growing into cities differed from life on the frontier, where practices were often influenced by contact with the Indians, both friendly and confrontational. Those who had come to America from rural areas and were competent farmers led lives often different from those who had come from the cities to escape from the specter of poverty. Judges in English courts frequently offered convicted felons, including those guilty of petty crimes, the option of jail or deportation to the colonies. In later years many criminals were exported to Australia, but America certainly had its share. The abundance of land and the need for labor in North America made it possible for many so-called criminal types to go straight, especially since the majority of crimes in the old country where those related to poverty and need.

In any case, as the quotation from Page Smith in an earlier section makes clear, society in America was to a large extent more diverse than the individual societies from which the settlers had come. A personal account of a wedding ceremony in New Jersey includes a description of a confused attendee who was befuddled by the mixture of English, German, Swedish, and other nationalities among the wedding guests. Although almost exclusively of Northern or Northwestern European stock, the thirteen American colonies were anything but uniform.

| Sage History Home | Colonial Home | Slavery In Colonial America | Updated June 1, 2020 |