| Lincoln's View | Radical Reconstruction | The Ku Klux Klan | Johnson's Impeachment |

| Grant as President | Reconstruction Ends 1877 | Redeemers in Power | Washington & Du Bois |

The Challenge of Freedom

References:

- Page Smith, Trial by Fire: A People’s History of the Civil War and Reconstruction (1982)

- W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America (1935)

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction, 1863-1877: America’s Unfinished Revolution (1988)

- Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (1966)

General. Reconstruction is the name given to the period between the end of the Civil War in 1877 when the last federal troops were pulled out of the South. Although the real process of reconstruction could not begin until the war ended, attempts at restoring the union were begun long before that. As far back as 1860 when the Confederate states were in the process of seceding from the Union, the Senate Crittenden committee was attempting to find a way to reverse the process that had already begun. They even proposed an amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing that slavery could continue where it already existed; it would have been the 13th amendment. (Ironically the 13th amendment that was finally enacted ended slavery.)

The Legacy of the Civil War

The Civil War was the bitterest war in American history by almost any definition. It has been called the “brothers' war,” the war between the states, or the “War of Northern Aggression,” and strong feelings about the background, causes, fighting, and meaning of the Civil War continue to this day. Over 600,000 Americans died during the Civil War and another 400,000 suffered grievous wounds. Millions of dollars worth of property were destroyed, families were disrupted, fortunes were made and lost, and the country that emerged from the war in 1865 was very different from the country that had existed in 1860.

Abraham Lincoln, considered by many to be America's greatest president, was viewed in the South past as an enemy at best, and at worst as a “bloodthirsty tyrant.” One Virginia woman expressed feelings very common at the end of the Civil War when she wrote in her diary: “I stood in the street in Richmond and watched the Yankees raise the flag over the Capitol with tears running down my face, because I could remember a time when I loved that flag, and now I hate the very sight of it!” As Southerners viewed the history of the prewar years, secession and the war itself, they began the process of writing their own history of those terrible events, and came to adopt what is called the “Lost Cause,” the idea that in the end the South had been right in its desire to govern itself and its “peculiar institution” of slavery. The idea—or, as some term it, the “myth”—of the Lost Cause is still present.

Reconstruction: The Historic Challenge

For most of the modern era the process of ending wars involved representatives of the warring nations sitting down at a table and arranging some sort of peace. Depending on the duration, the intensity and the issues over which the war was fought, peace settlements could range from harsh to generous. An unspoken but generally understood assumption was that the warring parties would be likely to meet on the battlefield again, with the results quite possibly reversed. Thus over-harsh settlements were rare.

Such a resolution was impossible following the American Civil War for the simple reason that the two warring parties—the Union and the Confederacy—were not held to be equal. The war had been fought over the Confederacy’s right to exist as a separate nation. The Union victory in effect ended the Confederacy’s claim to political independence. From the Union perspective there was no other party with whom to negotiate a peace settlement, which meant that it was up to the federal government to decide exactly how the defeated Confederate states were to be treated. In 1869 the Supreme Court in the case of Texas v. White ruled that secession was unconstitutional, which reinforced the notion that two separate nations have ever existed. The Court said that the Constitution “looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States.” See Texas v. White.

Lincoln’s View of Reconstruction

As early as 1863 president Lincoln began to think about reconstruction and offered a plan to allow states to begin to return to the Union in exchange for relatively mild concessions. Following Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg and Chattanooga, Lincoln hoped that at least some Confederate states might see the handwriting on the wall and be willing to rejoin the Union if generous terms were offered. Thus in December 1863 Lincoln issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which stated that those states where 10% of the 1860 electorate would take an oath of loyalty to the Union and agree to emancipation might be readmitted.

As early as 1863 president Lincoln began to think about reconstruction and offered a plan to allow states to begin to return to the Union in exchange for relatively mild concessions. Following Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg and Chattanooga, Lincoln hoped that at least some Confederate states might see the handwriting on the wall and be willing to rejoin the Union if generous terms were offered. Thus in December 1863 Lincoln issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which stated that those states where 10% of the 1860 electorate would take an oath of loyalty to the Union and agree to emancipation might be readmitted.

Congress refused to recognize Lincoln's plan and countered with the Wade-Davis Bill, a much harsher approach, which the president vetoed with a “pocket veto.” (Note: A pocket veto occurs when a bill is sent to the president, who does not sign it, but Congress adjourns within the 10-day period allowed for the president to return the bill.) Lincoln did not back off from his intention to treat the South generously. In his famous Second Inaugural Address, which is inscribed on the wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, he closed with the words:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Following Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, President Lincoln again outlined a generous plan for reconstruction. Sadly, the President did not live to see his ideas realized. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln went to Ford’s theater to attend to play with his wife. John Wilkes Booth, a Virginia actor enraged by the South’s defeat, made his way to the presidential box and shot the president in the head. Lincoln was carried across the street and placed in a bedroom, where he died the next morning. Lincoln’s assassination dealt a fatal blow to hopes for a more lenient reconstruction effort than what actually occurred. His death also had a chilling effect on potential sympathy for the South. Regarding Lincoln Winston Churchill wrote:

Others might try to emulate his magnanimity; none but he could control the bitter political hatreds which were rife. The assassin's bullet had wrought more evil to the United States than all the Confederate cannonade. ... [T]he death of Lincoln deprived the Union of the guiding hand which alone could have solved the problems of reconstruction and added to the triumph of armies those lasting victories which are gained over the hearts of men. (Winston Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (New York, 1966), Vol. 4, The Great Democracies, 263.)

Lincoln had been seen by many as a messiah, a notion enhanced by the fact that he died on Good Friday; even Southerners—those not consumed by bitterness—realized they had lost a friend.

Vice President Andrew Johnson succeeded to the presidency upon Lincoln's death. A non-slave-holding Senator from Tennessee who had remained loyal to the north, he ran with Lincoln on the Union Party ticket in 1864. Johnson carried a distinct animus toward the wealthy Southern planter class. He apparently intended to carry out Lincoln's generous reconstruction policies, but his motivations were quite different from those of Lincoln. He was prepared to have wealthy Southerners who had betrayed their country by serving the Confederacy dance to his tune. Powerful Republican Senators and Congressmen, thirsty for revenge and wanting a proper transition to freedom for the former slaves, visited with Johnson during the months following Lincoln’s death in order to assess his attitudes toward the defeated South. Initially, they came away satisfied that Johnson was on the right track. That assessment, however, would soon change radically. The next phase of Reconstruction began when Congress came back into session late in 1865.

Reconstruction for all practical purposes took place entirely within the South. Restoring the Confederate states to their former positions as part of the Union was a difficult process, and it was not completed successfully for a number of reasons. For most of the modern era the process of ending wars involved representatives of the warring nations sitting down at a table and arranging some sort of peace. Depending on the duration, the intensity and the issues over which the war was fought, peace settlements could range from harsh to generous. An unspoken but generally understood assumption was that the warring parties would be likely to meet on the battlefield again, with the results quite possibly reversed, and thus over-harsh settlements were rare.

Reconstruction for all practical purposes took place entirely within the South. Restoring the Confederate states to their former positions as part of the Union was a difficult process, and it was not completed successfully for a number of reasons. For most of the modern era the process of ending wars involved representatives of the warring nations sitting down at a table and arranging some sort of peace. Depending on the duration, the intensity and the issues over which the war was fought, peace settlements could range from harsh to generous. An unspoken but generally understood assumption was that the warring parties would be likely to meet on the battlefield again, with the results quite possibly reversed, and thus over-harsh settlements were rare.

Such a resolution was impossible following the American Civil War for the simple reason that the two warring parties—the Union and the Confederacy—were not held to be equal because the war had been fought over the Confederacy’s right to exist as a separate nation. The Union victory in effect ended the Confederacy’s claim to political independence, and thus from the Union perspective there was no other party with whom to negotiate a peace settlement. That meant that it was up to the federal government to decide exactly how the defeated Confederate states were to be treated. The conditions under which that had to be achieved were less than propitious, to say the least.

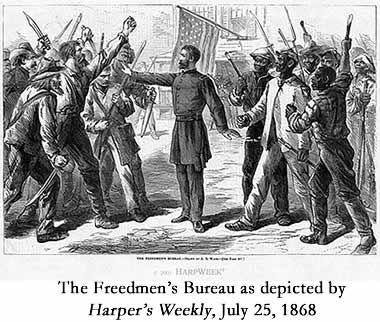

The South: From Slavery to Freedom. After the Civil War, the South faced a difficult period of rebuilding its government and economy and of dealing with over three million newly freed African Americans. The tragedy of Reconstruction was that blacks and whites who tried to form a more egalitarian society in the South lacked the means to achieve their aims. Many slaves who had been restricted all their lives had no "where" to go—although they were elated to be free: the great day of jubilation, it was called—but this new state of freedom also caused confusion. Some stayed on old plantations, others wandered off in search of lost family. Many slave owners were glad to get rid of "burdensome slaves" and threw them out "just like Yankee capitalists." Some former slaves, especially in cities like Charleston, celebrated their freedom in ways that whites considered “insolent”; they put on fancy clothes, paraded through the streets and showed none of their former deferential attitudes toward their former masters.

While some Freedmen celebrated openly, others, less trusting, approached their new status with caution. As they quickly learned, there was more to being free than just not being owned as a slave. When asked how it felt to be free by a member of an investigating committee, one former slave said, "I don’t know." When challenged to explain himself, he said, "I’ll be free when I can do anything a white man can do." One does not have to be a historian to know that degree of freedom was a long time coming.

The Meaning of Freedom: For African Americans, the most important single result of War was freedom—"the great watershed of their lives." Pertinent phrases include: "I feel like a bird out of a cage ... Amen ... Amen ... Amen!" Freedom came "like a blaze of glory." "Freedom burned in the heart long before freedom was born." The search for lost families was "awe inspiring." Some whites claimed that Blacks did not understand freedom and were to be "pitied." But Blacks had observed a free society, and they knew it meant an end to injustices against slaves. Blacks in the South also had a workable society—church, family and later schools. A Black culture already existed, and could be adapted to new conditions of freedom. Blacks also took quickly to politics. As one author has put it, they watched the way their former masters voted and then did the opposite. Remarkably, Southern Blacks exhibited little overt resentment against their former masters, and many adopted a conciliatory attitude. When they got into the legislatures they did not push hard for reform because they recognized the reality of white power.

(See Eric Foner, Reconstruction, 1863-1877: America's Unfinished Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), esp. "The Meaning of Freedom" pp. 77-88. Also Page Smith, Trial by Fire: A People's History of the Civil Was and Reconstruction (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), esp. "Freedom," pp. 597-630.)

Southern Attitudes: Many Southerners were enraged at the outcome of the war. Having suffered and bled and died to get out of the Union, they now found themselves back in it. A woman in Richmond wrote in her diary after the hated Yankees raised the American flag over the former Confederate capitol, “I once loved that flag, but now I hate the very sight of it!” Southerners recognized that they had to bow to the results of their loss, but did so with underlying resentment often bordering on hatred. Much ill feeling toward the North existed among the people who had stayed at home, especially in areas invaded by Sherman and others: wives, widows, orphans and those who had endured incredible hardships were particularly horrified to be back under federal control, ruled by their former enemies.

Many Southern whites, having convinced themselves in the prewar years that Blacks were incapable of running their own lives, were also unable to understand what freedom meant to Blacks. As one former slave expressed it, “Bottom rung on top now, Boss.” Many whites were still convinced slavery had been right. In a migration reminiscent of the departure of loyalists after the Revolution, many southerners took their slaves and went to Brazil, where the institution still flourished. Others went west to get as far away from “those damn Yankees” as they could.

(Along Interstate Highway 5 In Washington stands a monument to the Confederacy, one of a number of monuments raised by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and other groups in that state. The highway is named for Jefferson Davis.)

Northern Attitudes: The North was split on the question of reconstructing the South. Many Northerners, content to follow the lead of the White House, favored a speedy reconstruction with a minimum of changes in the South. Other Northerners, many of them former abolitionists, had the rights of the freedmen and women in mind. That faction favored a more rigorous reconstruction process, which would include consideration of the rights of freed African-Americans.

In the North, with the exception of thousands of shattered families, many with wounded veterans back in their midst, there was little to reconstruct, since most of the fighting was done in the South. Northerners buried their dead, cared for the wounded and did their best to get on with their lives. Although it is safe to say that the majority of Northerners were happy to see slavery gone, if for no other reason than the fact that the divisiveness of the issue had poisoned the political scene for decades, it cannot be assumed that the attitudes of Northerners were friendly to the full incorporation of blacks into the national fabric. On the other hand, most Northerners did expect the South to accept the verdict of the war and to do whatever would be necessary to reconcile themselves to the end of that “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Most Northerners felt little vindictiveness toward their southern brethren, but they lacked a sense of patience. The punishment of the South was very mild by comparison with other lost rebellions: Only one man was hanged, and there were few jail sentences for what many considered outright treason. No one was fined and there was no confiscation of property. But the South did have to accept certain things: the end of secession doctrine; the end of slavery; and the end of control of the South by the old southern aristocracy. Government of the South during the immediate postwar years was under Northern control.

(Henry Wirz, commander of the Andersonville, Georgia, prison camp was tried for murder, convicted and executed. Former Confederate President Jefferson Davis was imprisoned for a time at Fort Monroe, Virginia, but was soon released because of failing health.)

Northerners generally sought no “special” treatment of blacks. Some historians partial to the South have claimed that there was little of the misery, hatred and repression by which the South has been characterized, and that most of the South was peaceful and happy after the war. From a distance, it may have seemed that way; Northerners were obviously far less concerned with reconstruction than the South, but many were not happy about prospects of millions of blacks invading the northern job market, perhaps jeopardizing their economic security. Most white northerners wished blacks well, but weren’t willing to do much to help them. Nevertheless, teachers, including many women from New England, went South to help blacks. Other Northerners who went south included the so-called “carpetbaggers,” men who went south in order to commercially or politically exploit the situation for their own ends. (The epithet comes from the cheap suitcases they carried, which were made of pieces of carpet sewn together.) Although infamous in their time (and after), recent studies have argued that they often did much good by helping to modernize the South by promoting education and commerce.

Once Northerners had honored and mourned their dead and taken care of widows and orphans, they got back down to work building railroads, factories, businesses, settling the west, fighting the Indian wars and finding room for the 25 million immigrants who came to the United States between 1865 and 1910. One significant result of the war for the North was the fighting experience of thousands of soldiers who became laborers in the growing industries and often used the same tactics they employed on the battlefield against their bosses.

Constitutional Silence: In the absence of constitutional guidelines, the president and Congress waged a bitter fight over how best to reconstruct the Union. The North was split on the question of reconstructing the South. Some Northerners, led by the White House, wanted speedy Reconstruction with a minimum of changes in the South. Other Northerners, led by Congress, wanted a slower and more rigorous Reconstruction and demanded that the freed African-Americans be protected. In fact the struggle between Congress and the President went outside the context of Reconstruction and became a fight in its own right, leading to the impeachment of Johnson in 1868.

Reconstruction was a complicated legal and political issue: What was the legal status of the former Confederacy? Were the rebellious states still in the Union? Lincoln encouraged states to rejoin the Union under liberal terms without increasing resistance in states still fighting. As mentioned above, the Crittenden Committee made attempts at compromise, but those attempts were bound to fail, given the mood in 1861.

The Thirteenth Amendment. When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he was concerned that the measure might be unconstitutional. Congressional Republicans shared the president’s concerns, in that the proclamation was a war measure and might be invalid once the war was over. At Lincoln’s urging, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment in 1864. Article I reads:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Lincoln made passage and ratification of the amendment to abolish slavery a campaign issue in the election of 1864. The amendment was ratified by the requisite number of states in December, 1865.

Reconstruction Politics: A Power Struggle: Reconstruction was also part of the ongoing struggle over political power in the government of the United States. President Andrew Jackson, who saw himself as guardian of the people, sought to protect them from excessive government interference in their lives by using the veto power liberally, thus reducing what he saw as an abusive misuse of power by Congress. An entire party—the Whigs—came into existence over that issue during Jackson’s reign, as members of Congress considered his vetoes executive tyranny. (Two presidents, John Tyler and Andrew Johnson, faced impeachment charges over the issue of presidential vetoes, although the vote to impeach President Tyler did not pass in the House. Johnson's impeachment is discussed further below.) Members of Congress nicknamed Jackson “King Andrew,” resenting his defiance of what many felt should be the dominant branch of the government. The Radical Republicans who took control of Reconstruction after the elections of 1866 included many old Whigs who had memories of their tussles with Old Hickory.

Like Andrew Jackson, President Lincoln had also been a powerful political leader during the Civil War, and Congress sometimes bridled under his forceful direction of the government. The President’s veto of the Wade-Davis Bill was but one occasion when he and Congress were at odds. Lincoln's assassination and the accession of Vice President Andrew Johnson to the highest office in the land set the stage for a showdown between Congress and the White House. Some members of the House and Senate even felt a need to move toward a system similar to that in Great Britain, where the head of state—the monarch, Queen Victoria during those years—was becoming more of a figurehead than a political force. In fact, the struggle between Congress and the President moved outside the context of reconstruction and became a fight in its own right, leading to the impeachment of President Johnson in 1868. That conflict between the institutions at opposite ends of Pennsylvania Avenue meant that reconstruction was bound to be a challenging endeavor.

The Legal Issue. Since the Constitution contained no provision for the legal separation of the states, there was naturally no provision included for reuniting a divided Union. What, then, was the legal status of the former Confederacy? Were the rebellious states still in the Union? The Supreme Court eventually ruled on the matter in an important and often overlooked decision, the 1869 case of Texas v. White. In that case, which arose over the matter of bonds issued by the Confederate government of Texas, the Court held that secession was inadmissible under the Constitution and that the Confederate states had never existed legally. In its decision the Court stated, “The Constitution … looks to be an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible states.” The argument hinged on the fact that the Articles of Confederation said that “the Union shall be perpetual,” and the preamble to the Constitution called for a “more perfect Union.” In fact the term "Perpetual Union" appears six times in the Articles of Confederation. Nevertheless, the Court stated, Congress could dictate the terms under which the seceded states could rejoin the Union because of Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution, which states: “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.” As Texas v. White was not decided until 1869, the president and Congress continued to wage a bitter fight over how best to reconstruct the Union.

In contrast to the relatively lenient and passive approach of Lincoln and Johnson, the radical Republicans, the liberal wing of the Republican Party, favored a much tougher approach. They were idealists, many of them driven by an almost religious fervor. They did not accept the commonly held notion that blacks were inferior, and they therefore insisted on full political, social and civil rights for the former slaves. In this sense they were true reformers, in many ways far ahead of their time, and they had very different ideas about reconstruction from those of Lincoln and Johnson. (How Lincoln’s thinking on reconstruction might have evolved over time can, of course, never be known.) The radicals thought Lincoln was too easy on the South and wanted to overturn Southern cultural institutions and practices; they wanted to see the South rebuilt according to a new order. Northern Republican newspapers such as the New York Tribune agreed. Radicals believed that the South should be treated as territories rather than states and that the rebel states had committed political suicide. They claimed that no state governments could exist in the South until Congress restored them under any conditions it deemed necessary.

Following Lincoln’s death, congressional Republicans held hearings on conditions in the South which revealed widespread mistreatment of blacks, including random incidents of violence. More formal attempts at controls, as demonstrated by the Black Codes drawn up in many states, also surfaced. Black Codes prohibited blacks from owning firearms, required them to be employed or face vagrancy charges, imposed fines which could be worked off by labor, and placed other restrictions on their freedom. For all practical purposes, the codes recreated slavery in a form under which the state rather than individuals purposes owned the slaves. Postwar Southern governing officials understood that the slave codes that had existed prior to the Thirteenth Amendment had to be repealed. But the new codes went far beyond what was necessary to remove the former restrictions, and limited the freedom of the former slaves in the process. (See the Mississippi Code in the Appendix, for example.)

Following Lincoln’s death, congressional Republicans held hearings on conditions in the South which revealed widespread mistreatment of blacks, including random incidents of violence. More formal attempts at controls, as demonstrated by the Black Codes drawn up in many states, also surfaced. Black Codes prohibited blacks from owning firearms, required them to be employed or face vagrancy charges, imposed fines which could be worked off by labor, and placed other restrictions on their freedom. For all practical purposes, the codes recreated slavery in a form under which the state rather than individuals purposes owned the slaves. Postwar Southern governing officials understood that the slave codes that had existed prior to the Thirteenth Amendment had to be repealed. But the new codes went far beyond what was necessary to remove the former restrictions, and limited the freedom of the former slaves in the process. (See the Mississippi Code in the Appendix, for example.)

Those factors intensified Radical feelings about a heavy-handed reconstruction process. Congressional moderates had more modest goals—to protect blacks but not to grant them full equality or any special favors. Johnson’s reaction to Congressional initiatives, however, eventually drove many moderates into the radical camp.

The Battle Lines Are Drawn. The fact that President Johnson was a Democrat, placed on the National Union party ticket in 1864 by President Lincoln in order to balance the team, did not help. His demeanor often left much to be desired as well. (He had been drunk during President Lincoln's second inaugural celebration.) Since Congress was not in session when the war ended, Johnson proceeded to carry out what he honestly believed was Lincoln's policy. Radical leaders still in Washington visited Johnson shortly after the war ended and came away satisfied that he would do things properly.

President Johnson issued a proclamation of amnesty on May 29, 1865, citing Lincoln’s original attempts at reconstruction as background. (See Appendix.) Exceptions to the blanket amnesty were made for those who had held prior federal office and later occupied positions in the Confederate government, but those persons would be dealt with by “special application” to the President for the sake of “the peace and dignity of the United States.” Over the course of the summer of 1865, President Johnson dispensed pardons liberally to many former high-ranking confederates. Johnson apparently took pleasure at the spectacle of former Southern aristocrats, some of whom had previously scorned him, having to plead their case before him.

By the time Congress returned on December 4, 1865, President Johnson was satisfied that reconstruction had been completed. The Radical Republicans who dominated Congress were not so sure. If the president asserted that the former Confederate states had been readmitted, however, how was Congress to assert its will? The answer lay in the Constitution, which states in Article I that, “Each house shall be the judge of the … qualifications of its own members.” When Southern legislators returned to Washington in December, 1865, they were turned away. In the first place, some of the newly-elected Congressmen had served as officers in the Confederate armies, and they belonged to the opposition Democratic Party. Furthermore, Republicans feared that they would lose control of Congress because the 3/5 rule for counting slaves was gone as a result of the Thirteenth Amendment—they would henceforth all be counted. By refusing to seat their congressional delegations, Congress effectively denied the former Confederate states readmission to the Union.

By the time Congress returned on December 4, 1865, President Johnson was satisfied that reconstruction had been completed. The Radical Republicans who dominated Congress were not so sure. If the president asserted that the former Confederate states had been readmitted, however, how was Congress to assert its will? The answer lay in the Constitution, which states in Article I that, “Each house shall be the judge of the … qualifications of its own members.” When Southern legislators returned to Washington in December, 1865, they were turned away. In the first place, some of the newly-elected Congressmen had served as officers in the Confederate armies, and they belonged to the opposition Democratic Party. Furthermore, Republicans feared that they would lose control of Congress because the 3/5 rule for counting slaves was gone as a result of the Thirteenth Amendment—they would henceforth all be counted. By refusing to seat their congressional delegations, Congress effectively denied the former Confederate states readmission to the Union.

Nevertheless, President Johnson declared on December 6 that the Union was restored, which angered the Republicans, who then set out their own plan for reconstruction, quite different from that proposed by the president. In February, 1866, a new Freedmen’s Bureau Bill was passed to counteract the Black Codes. Johnson vetoed the bill, further angering the Radicals, and his veto was quickly overridden. In March Congress passed the Trumbull Civil Rights Act, which was designed to counter the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case by granting blacks citizenship. The act affirmed the right of freedmen to make contracts, sue, give evidence and to buy, lease and convey personal and real property. The act excluded state statutes on segregation, but did not provide for public accommodations for blacks. Johnson again vetoed the bill on constitutional grounds and also on the grounds that Southern Congressmen had been absent. Again, he was overridden.

The Fourteenth Amendment. Johnson's vetoes infuriated the radical leaders. In June they passed the Fourteenth Amendment because they feared that the Trumbull Civil Rights Act might be declared unconstitutional. Section 1 of the Amendment states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment was eventually made a condition for states to be readmitted to the Union. The radicals continued to uphold their exclusion of Southern Congressmen on grounds that by excluding blacks from the political process, the Southern governments were not republican in form, which constituted a violation of the Constitution’s Article IV, Section 4.

Every Southern state legislature except that of Tennessee refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. Instead, they persisted in applying Black Codes to the freedmen and denying them voting and other rights. Mistakenly thinking that the radical approach to reconstruction was out of tune with Northern sentiment, the South decided to wait things out, pending the results of the 1866 congressional elections.

The 1866 Elections. In August, 1866, the National Union Party, on which Lincoln and Johnson had been elected in 1864, challenged the Republicans for the upcoming congressional elections. During the fall campaign President Johnson went on a speaking tour in opposition to the Radicals, but his maladroit addresses simply aroused indignation and turned the voters toward the Republicans, who returned an overwhelmingly radical Congress. The huge Republican victory gave them a 43-11 majority in Senate, and 143-49 in the House. With 3-1 majorities in both houses and veto overrides certain to follow, the Radicals proceeded to take control of reconstruction—the president would be powerless to stop them. The overwhelming results rendered Andrew Johnson virtually irrelevant.

Radicals in Power. The first item on the radical agenda was a determination to crush the old southern ruling class. Radical reconstruction soon became what one historian has called a “states’ righters’ nightmare” and an “exquisite chastisement” of the South. The first Reconstruction Act was passed in March 2, 1867. It divided the former Confederate states into five military districts and declared that the existing state governments were provisional only. The states were required to call constitutional conventions with full manhood suffrage and to enroll blacks on voter rolls. They would then be required to ratify their new state constitutions as well as the Fourteenth Amendment; then and only then would their representatives be readmitted to Congress.

President Johnson fought the Reconstruction Act by appointing governors who refused to vigorously enforce them. The states in turn stonewalled and refused to comply, finding loopholes in the act to avoid their full execution. At the same time Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act, they also passed the Tenure of Office Act and the Command of the Army Act. The Tenure of Office Act was aimed at keeping Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Radical sympathizer, in his position. The act stated that Johnson could not dismiss cabinet officers who had been confirmed by the Senate without Senate approval. The Command of the Army Act was designed to control the president by requiring all reconstruction actions to go through the Commander in Chief of the Army, General Grant, also a Republican sympathizer. The two acts would later form the basis for President Johnson's impeachment.

Responding to Southern resistance to the first Reconstruction Act, in 1867 and 1868 Congress passed three supplementary Reconstruction Acts designed to close loopholes in the original act Those acts granted more authority to military governors and allowed simple majorities of the voters rather than majorities of the full population to decide elections. (Southerners tried to avoid the provisions of the Reconstruction Acts by advising white voters to boycott elections.)

The Reconstruction Acts, which President Johnson reluctantly carried out, resulted in what has been called “military reconstruction.” The military districts were overseen by U.S. Army generals, and Union soldiers were still present in the South. The Republican party in the South grew strong, as some 700,000 blacks were registered to vote, which meant that blacks comprised a majority of voters in many areas of the South. The Republican Party in the South also consisted of former Unionists and northern Republicans who had moved south, the carpetbaggers, so called because of the cloth suitcases they carried. Many of those northerners went South after the war for various reasons. Some went to help Blacks get an education or assist them in other ways. Some went because they saw opportunities to make a fast buck. They were almost universally scorned by Southerners.

The Southern State Conventions were dominated by Radical Republicans, and blacks participated in all of them. The new constitutions were generally quite progressive and often ahead of those of the North in terms of expanded rights. They guaranteed civil rights for blacks and excluded former Confederates from high positions in government.

White Counterrevolution: The KKK. In the months following the end of the Civil War many whites carried out acts of random violence against blacks. In their frustration at having lost the war and suffered great loss of life and property, they made the former slaves scapegoats for what they had endured. The violence became more focused when the Ku Klux Klan was founded in December, 1865. The Klan and other white supremacy groups, such as the Knights of the White Camellia, the Red Shirts and the White League, were well underway by 1867. The target of the Klan was the Republican Party, both blacks and whites, as well as anyone who overtly assisted blacks in their quest for greater freedom and economic independence.

The result was what can only be called a reign of terror conducted by the Klan and other groups over the following decades. Thousands were killed, injured or driven from their homes or suffered property damage as buildings were burned and farm animals destroyed. Blacks who tried to further the cause of the Republican Party were singled out for attack, as were whites who, for example, rented rooms to northern carpetbaggers, including school teachers. Black men were beaten within an inch of their lives or even to death in front of horrified family members. The fear of night riders often drove blacks into the woods to sleep because they felt they were not safe in their own homes. (See Judge Albion Tourgee, Appendix)

The result was what can only be called a reign of terror conducted by the Klan and other groups over the following decades. Thousands were killed, injured or driven from their homes or suffered property damage as buildings were burned and farm animals destroyed. Blacks who tried to further the cause of the Republican Party were singled out for attack, as were whites who, for example, rented rooms to northern carpetbaggers, including school teachers. Black men were beaten within an inch of their lives or even to death in front of horrified family members. The fear of night riders often drove blacks into the woods to sleep because they felt they were not safe in their own homes. (See Judge Albion Tourgee, Appendix)

Former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, reported to be the first Grand Wizard of the Klan (though he claimed be never had control), formally disbanded the KKK in 1868 because of increasing violence. Nevertheless, the group continued exist and to wreak vengeance upon freedmen and their white supporters. Eventually the Congress passed Force Bills in 1870 and 1871 to control the violence and protect blacks from being deprived of their civil and political, but enforcement of those acts was often lax, and other means of intimidation often proved effective.

Despite efforts to control the violence, lynchings in the South remained common throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. They were performed in public to further intimidate blacks, who realized that they remained vulnerable, and that the perpetrators would not be punished, even though it was obvious who the guilty parties were. Almost any action deemed unacceptable by whites could lead to a lynching, including looking too closely at a white woman, talking disrespectfully to whites or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson. President Johnson had infuriated the Radicals with his vetoes, even though they were overridden. When the president tried to sabotage radical reconstruction by failing to administer it vigorously, Congress decided to try to remove him from office. Johnson suspended Secretary of War Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, which gave the Radicals an issue on which to proceed. In February 1868 the House voted to impeach the president by a vote of 126-47 for violating the acts and “attempting to bring disgrace and ridicule on Congress.” Johnson was well defended in his trial before the Senate and was wise enough to stay away from the capitol and leave his defense to his attorneys.

Meanwhile popular opinion had begun to turn against the Radical Republicans. Many citizens believed they were willing to subvert the Constitution in order to accomplish their political goals. The Radicals were forced to acknowledge that impeachment was indeed a political act—a test of the power of Congress. Some of them would have the legislature become “as powerful as the British,” rendering the president little more than a figurehead. It was also personally directed against Johnson. The final outcome of the Senate trial failed to convict Johnson by a single vote. It may have been rigged because of fear that Ben Wade, an extreme radical, President pro Tempore of the Senate and next in line for the White House, might have the advantage in the election of 1868. The final vote of 35-19 left Johnson chastised, and he carried out reconstruction for the remainder of his term without further incident.

(Note: Article I of the Constitution leaves succession to the presidency if the office of vice president is vacant up to Congress. The current succession act, passed in 1947, makes the Speaker of the House next in line after the vice president. Until the 25th Amendment was ratified in 1967, there was no provision for replacing the vice president in case of removal by death or resignation. Although eight presidents died while in office prior to that time, the office of vice president was always filled on those occasions, so the succession act has never been used.)

States Readmitted. By June 1868 Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama and Florida had been readmitted to the Union. Many of the governors, representatives and senators in those states were Northern carpetbaggers who took advantage of the opportunity to establish political careers by joining with black Republicans. African Americans gained majorities in the legislatures of Louisiana and South Carolina. Mississippi, Texas and Virginia were readmitted to the Union in 1870. Georgia was actually removed briefly after passing a bill barring blacks from political office. In order to continue to be represented in Congress, they had to repeal the act.

The Fifteenth Amendment. In 1869 Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which stated that, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The amendment was finally ratified in 1870, and well over half a million black names were added to the voter rolls during the 1870s. The Force Acts (see below) were further attempts to suppress terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, which had become strong enough to seize political control of some Southern states.

Although the Fifteenth Amendment was meant to ensure voting rights for all males, such devices as poll taxes and literacy tests were used to subvert the purpose of the amendment. Poll taxes had to be paid two years in advance, and the financial burden was stiff for blacks. (Poor whites could procure election “loans” to enable them to vote.) Literacy tests were used to restrict blacks, and alternatives such a passing a test on the Constitution were often rigged in favor of whites. By the turn of the century, as a result of such things as amended state constitutions, grandfather clauses and gerrymandering, black voting in the South had been reduced to a fraction of its former numbers. By 1910 few blacks could vote in parts of the South; thus, a vast contrast existed between the earlier goals of the abolitionists and the reality of everyday life for freedmen in the South. This condition persisted until the modern civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s.

The Election of 1868. The Republican choice for president in 1868 was General Ulysses Grant, who, along with President Lincoln, was deemed the savior of the Union. His Democratic opponent was former Governor Horatio Seymour of New York. Grant won the presidency in a fairly close election, as more than 450,000 blacks voted for the former Union general.

Serving during one of the most difficult periods in American history, Grant lacked the consistency and sense of purpose to be an effective administrator. On the battlefield he had always been able to select competent commanders for the brigades and divisions in his armies. Once he gave his orders, which were generally concise and clear, he was content to let generals like Sherman, McPherson, Schofield, and others carry out their missions without interference. Never a martinet, Grant was a thoughtful, careful, yet daring field commander, one of the most successful generals in American military history.

In the White House, however, Grant faced problems that might have defeated a more experienced president, but he did not always help himself. Lacking political skills or strong political principles, he was by temperament not well suited to the job. Just as he had been an un-military general, he was an un-political president.

Above all, President Grant sought reconciliation between North and South in order to heal the wounds of the Civil War. He ended his first inaugural address with these words:

In conclusion I ask patient forbearance one toward another throughout the land, and a determined effort on the part of every citizen to do his share toward cementing a happy union; and I ask the prayers of the nation to Almighty God in behalf of this consummation.

Grant’s hands-off approach to military command did not work well in a political setting. He was unable to read the political landscape with the sharp eye he had employed in combat, and some of his appointments were unfortunate. As a result, his administration was tainted by controversy and corruption. Although never personally implicated in the misfeasance of his subordinates, Grant was unable to see the damage it was doing to his administration. The troubles included the “Credit Mobilier” scandal, in which Union Pacific Railroad managers formed a company to divert profits to themselves and others and gave shares in the company to politicians in order to get favorable legislation passed. Grant's reputation as a general has always been high, but he was long thought to have been a failure as president. Recent scholarship, however, has gone far in reevaluating Grant's years in the White House. (See especially Grant, by Jean Edward Smith (New York, 2001).

Grant’s hands-off approach to military command did not work well in a political setting. He was unable to read the political landscape with the sharp eye he had employed in combat, and some of his appointments were unfortunate. As a result, his administration was tainted by controversy and corruption. Although never personally implicated in the misfeasance of his subordinates, Grant was unable to see the damage it was doing to his administration. The troubles included the “Credit Mobilier” scandal, in which Union Pacific Railroad managers formed a company to divert profits to themselves and others and gave shares in the company to politicians in order to get favorable legislation passed. Grant's reputation as a general has always been high, but he was long thought to have been a failure as president. Recent scholarship, however, has gone far in reevaluating Grant's years in the White House. (See especially Grant, by Jean Edward Smith (New York, 2001).

In the South, Grant’s administration initially failed to sustain black suffrage against violent groups bent on restoring white supremacy. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan used terrorism, insurrection and murder to intimidate southern Republican governments and prospective black voters. With the Fifteenth Amendment severely threatened, Congress finally passed Enforcement, or Force Acts of 1870 and 1871, sometimes called the “Ku Klux Klan Acts”, which allowed the president to use military forces effectively to quell insurrections and keep violence away from polling places. Vigorously enforced in South Carolina, they were used sporadically elsewhere in the South.

Grant’s Second Term. Despite scandals caused by some members of his administration, as well as support from many liberal Republicans for New York Tribune publisher Horace Greeley, Grant was reelected in 1872. His reelection bid was aided by the successful conclusion of treaty with Great Britain over war claims negotiated by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish in 1871. (Discussed further below. Fish was clearly Grant’s most successful appointment.)

During his second term Grant’s attention began to shift from Reconstruction matters to more general issues of concern to the country. During the Civil War the Union had issued paper money not backed by specie, known as greenbacks. Following the war there was pressure to return to “hard money,” but pressure for inflationary policies kept them in circulation into the 1870s. In 1873 a new currency act was passed to return the county to the gold standard. Speculation in gold markets led to a financial crash, which created a financial panic that led to a depression that hung over the nation for several years.

In 1875 Congress passed the Sumner Civil Rights Act, which stated, “That all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” It also stated that blacks could not be excluded from jury duty, and provided for criminal penalties for violations of the act. The Sumner Act was designed to go further than the Fourteenth Amendment in providing “social rights,” but after Reconstruction ended in 1877, it was rarely used. In 1883 the Supreme Court ruled the act unconstitutional on the grounds that the Fourteenth Amendment did not require equality in areas controlled by private interests.

The Physical Reconstruction of the South: Much of the South was physically devastated and demoralized after the war. Railroads and factories had been destroyed, farms had gone unattended, and livestock had been killed or driven off in areas occupied by the Union armies. The former plantation owners still had their land but had lost much if not all of their capital. The former slaves comprised a large and experienced labor force but owned neither land nor capital. Many former slaves believed in the precedent set by General Sherman, that the federal government was going to supply them with “forty acres and a mule.” Sherman, however, had exceeded his authority, and the Constitution inhibited the ability of the government to confiscate or claim private property “without due process of law.”

Black leaders in the South who participated in the Reconstruction governments did not always understand the land problem. Many Blacks who gained office had been free before the war, had lived in cities or towns, and had not been directly connected with agriculture. Those who gained public office often came from those groups; they were generally literate and had relatively little in common with plantation field hands. Even among the former slaves themselves there were significant differences in the way they saw their situation; those slaves who had been artisans and had worked at jobs other than simple farming had more opportunities than those who simply needed land on which to live and raise crops.

Some sort of system of production had to be worked out, and what evolved was a combination of various plans that on the surface seemed reasonable: sharecropping, tenant farming and the crop lien system. Sharecropping meant that those working the land would share the profits from their crop sales with landowners; tenant farmers simply rented the land; the crop lien system allowed farmers, in effect, to mortgage their future crops with owners. Each system had as its basis a bargain among laborers, those who had land and those who owned or controlled capital. Each system was potentially beneficial to all parties, but each also contained the possibility of exploitation and fraud, as was shown in practice. Even poor whites became sharecroppers or tenant farmers, so there was nothing inherently discriminatory in any approach. In fact, by 1880 a significant portion of the former slaves had become landowners, and despite exploitation and abuses, the system brought a moderate amount of cooperative self-reliance to the parties involved. Nevertheless, many former slaves still found themselves caught in a system that offered few rewards beyond mere subsistence.

The South also needed capital to rebuild railroads and make other internal improvements, and those needs generated a reawakening of the South in the post-Civil War years that slowly brought new prosperity to the region. It was hard won, however, and many of the losses suffered by the Confederacy were never regained. The economic ups and downs of the industrial era often hit the South especially hard. The South was not always seen as a favorable region for the investment of capital, especially in periods where capital was in short supply. Railroad building tended to be concentrated in the trans-Mississippi area.

Despite attempts at industrialization, the South produced a smaller national portion of manufactures in 1900 than in 1860. The South had 30% of the population, 50% of the farmers. By 1880 the average annual income in South was half that of the national rate. The high occurrence of tenancy resulted in economic slavery for many. The Redeemer regimes, often corrupt, welcomed Northern investment, and Northern control of Southern economy. These governments neglected the problems of small farmers, black or white, who suffered from unpayable debts. Eventually, the small farmers of the South joined in the creation of a new political party, called the Populists, in the 1880s. (See next section.) The Redeemers also began the process of legal segregation and invented ways of denying blacks the right to vote. North and South united, but at a heavy cost to the newly freed blacks. (Note: Redeemers is the term applied to Democratic politicians who generally shared the views of majority whites in the prewar South.)

End of the Reconstruction Era: The Compromise of 1877

By 1876 many people both North and South had grown tired of reconstruction and wanted to forget the Civil War altogether. It had become apparent that the problems of the South could not be resolved by tough federal legislation, no matter how well intended. In May 1872, Congress passed a general Amnesty Act, which restored political rights to most remaining confederates. The Democratic Party was restored to control in many Southern states, and black voting rights began to be curtailed by one means or another.

The election of 1876 was the vehicle by which Reconstruction was finally ended. The candidates were former Union General Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, Republican, and New York Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden. The campaign was carried out by far less than above-board means, with corruption and treason being some of the charges which the parties leveled at each other. Hayes was called to answer for the “crimes” of the Grant administration, while Republicans continued to call the Democrats the party of treason. That charge became known as the “bloody shirt,” so called because of a politician who waved a blood-stained shirt at a convention, blaming the South for the war. White supremacy groups helped spread pro-Democratic propaganda throughout the South. As the campaign drew to a close, Tilden was regarded as the favorite, and on the final night of voting, even Hayes believed that he had lost as he retired for the night. It soon became apparent, however, that the results were unclear.

The election of 1876 was the vehicle by which Reconstruction was finally ended. The candidates were former Union General Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, Republican, and New York Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden. The campaign was carried out by far less than above-board means, with corruption and treason being some of the charges which the parties leveled at each other. Hayes was called to answer for the “crimes” of the Grant administration, while Republicans continued to call the Democrats the party of treason. That charge became known as the “bloody shirt,” so called because of a politician who waved a blood-stained shirt at a convention, blaming the South for the war. White supremacy groups helped spread pro-Democratic propaganda throughout the South. As the campaign drew to a close, Tilden was regarded as the favorite, and on the final night of voting, even Hayes believed that he had lost as he retired for the night. It soon became apparent, however, that the results were unclear.

The winter of 1876-1877 thus became one of confusion and bitterness as the outcome of the election was smothered in doubt. To this day it is not certain who really won. When the electoral votes had been counted, the election returns in three Southern states—South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana—were in question. Because of alleged intimidation and other reasons, charges arose that the election had been stolen in those three states. The apparent results gave those three states to Hayes, which meant that he would have won in the Electoral College by one vote; but if any of those results were overturned, Tilden would have become the victor. The question was: how could the conflict be resolved?

President Grant’s mediation in the affair helped avert a national crisis, but the country still faced a difficult and messy problem. Congress did what it usually does when confronted with a political imbroglio: it formed a committee. Originally the committee was comprised of seven Republicans, seven Democrats and one independent: five Congressmen, five senators and five Supreme Court justices. But when it turned out that the independent had become ineligible, he was replaced by a Republican, and they now had an 8-7 majority on the committee.

When the returns in the three states were examined, the committee decided not to “go behind the returns”—that is, they decided to accept the results as presented to Congress, in each case by a vote of 8 to 7. Thus all three states were given over to Hayes, but not without a fight. Democrats in Congress threatened to refuse to accept the committee recommendations. That action would have thrown the nation into turmoil, with no new president to take office on March 4. Behind closed doors, in smoke-filled rooms, a deal was hatched: In return for allowing the committee's recommendations and giving the election over to Hayes, the Democrats exacted three promises. First, reconstruction would be ended and all federal troops would be removed from the South. Second, the South would get a cabinet position in Hayes’s government. Third, money for internal improvements would be provided by the federal government for use in the South.

The irony of the situation is that President Hayes was probably prepared to do those things in any case, but the Compromise of 1877 was accepted. In April of that year federal troops marched out of the South, turning the freedmen over (as Frederick Douglass put it) to the “rage of our infuriated former masters.”

Summary of Reconstruction

The Civil War was the bitterest war in American history by almost any definition. It has been called the “brothers' war,” the war between the states, or the “War of Northern Aggression.” Strong feelings about the background, causes, fighting and meaning of the Civil War continue to this day. Over 600,000 Americans died during the Civil War and another 400,000 suffered grievous wounds. Millions of dollars’ worth of property were destroyed, families were disrupted, fortunes were made and lost, and the country that emerged from the war in 1865 was very different from the country that had existed in 1860.

In the immediate aftermath of the war its most serious consequence was undoubtedly the rage that swept across the South, manifesting itself in bitterness and hatred of all things associated with the Union—or the North. “Yankee” was a pejorative term, and “damn Yankee” was one of the milder epithets applied to anyone who came from the far side of the Mason-Dixon line. (One of my former students who married a Southerner said that she had lived in the South for twenty years before she knew “damn Yankee” was two words.) The South saw a huge portion of its young male population destroyed, along with homesteads, farms, factories and railroads. After all the sacrifice and suffering that Southerners had endured, they were back in that hated Union.

Naturally the rage and frustration felt by many Southerners needed a target or outlet, and unsurprisingly, that target was the freedmen and women, the former slaves who now walked unfettered in the streets of Charleston, Atlanta, Mobile and New Orleans. Their very presence as free men and women further aggravated feelings of Southerners like salt in a wound, and their wrath was often expressed by bloody and violent means.

Reconciliation of the two sections of the country came at the expense of Southern blacks and poor whites. North and South reconciled after 1877, but only through the compromise that stripped African-Americans of their political gains and turned the South back over to the Redeemer Democratic governments that sought to further legislation restoring white supremacy through Jim Crow laws and other means. The “New South” of the Redeemers would recreate as far as possible the racial conditions of the Old South. The Southern economy was dominated by Northern capital and Southern employers, landlords and creditors. Economic and physical coercion, including hundreds of lynchings, effectively disenfranchised people of color. Some blacks, justifiably bitter at the depth of white racism, supported Black Nationalism and emigration to Africa, but most chose to struggle for improvement within American society. Over time, many migrated north or west in search of better opportunities.

The results of the Civil War included the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments that ended slavery, created national citizenship for the first time, amplified the meaning of the Bill of Rights, and attempted to provide access to the democratic process for all adult male Americans. They were, in the short term, only partially successful at best.

As Southerners viewed the history of the prewar years, secession and the war itself, they soon began the process of writing their own history of those terrible events, and came to adopt what is called the “Lost Cause,” the idea that in the end the South had been right in its desire to govern itself and the defend the institution of slavery. The idea—or, as some term it, the “myth”—of the Lost Cause is still present. (See Edward A. Pollard. Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, 1866)

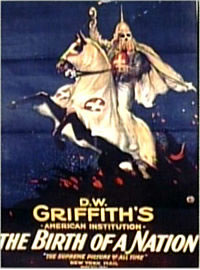

In 1915 movie maker D.W. Griffith produced one of the most famous and controversial films in American history, The Birth of a Nation. In terms of its contributions to the history of cinematography, the film is a masterpiece. With a running time of over three hours, it was long even by today's standards. A black and white silent film, it nevertheless used color tinting for dramatic effects, employed hundreds of extras, and had elaborate subtitles and other graphic effects. The film, however, was overtly racist. Its theme was the salvation of the reconstruction South by the Ku Klux Klan from rampaging former slaves and northern opportunists. Race riots over the film broke out in some northern cities, and the N.A.A.C.P. protested in cities across the country. Although President Woodrow Wilson showed the film in the White House and proclaimed it good history, in later times critics have condemned the content of the film for its overt racism and historical inaccuracies.

Conclusion. It is hard but not impossible to say good things about reconstruction. In later years, some Blacks looked back on Reconstruction as “the good old days,”—a time when anything seemed possible; two Black men served in the Senate, one in the House, and there were Blacks in most Southern governments. Their goals were land, the ballot and education for Freedmen. Blacks did get the ballot, and education opportunities were provided. Congress could not support land confiscation, however, as it was legally barred. There was no “Marshall Plan” for the South, but on the other hand, the South was not brutalized. Despite the enormous problems of the Reconstruction era, the hope existed among many that further progress could be made. Many honest citizens, both black and white, understood the challenges and worked to solve them; nevertheless, many goals were unrealized, and much of the progress that was made during Reconstruction was reversed later.

Perhaps the greatest irony of reconstruction is that it had to occur at all in a legal sense. For four years a bloody war had been conducted to prove the point that a state could not unilaterally leave the Union. During the years after the war was over, however, the United States Congress dictated terms under which the states would be admitted back into the Union.

Like the Civil War that preceded it, the reconstruction experience changed life in the American South, and to some extent even in the north, permanently. In the first place, the leadership of the old plantation-slave-owning aristocracy was undermined. It was a bitter pill for those who had shaped the fortunes and destinies of most of the southern population. Although it existed in nostalgic memories for some time, the old South was gone. To some extent, the old leadership tried to hold onto power through black codes and other measures. Neither did the Republican radicals in Congress understand the degree to which Southern conservatives could conspire to flout federal laws. Furthermore, leadership at all levels, North and South, was insufficient to meet the extraordinary challenges of reconstruction.

Although the “Black Republican” governments in the South were accused of corruption, dishonesty and shady dealings in government were typical of the time, especially in the northern cities. Political leadership was insufficient to meet the challenges of government, and corruption among politicians was widespread. In terms of how the federal government conducted business during Reconstruction, many historians have decided that the radicals were not radical enough; they left too much undone, and walked away while the readjustments were still far from complete. When Frederick Douglass said, “you turned us loose to the wrath of our infuriated masters” he might have said “former masters” Yet with the black codes and other legal and extralegal methods devised to control the population of Freedmen, in a sense he was still correct.

In the end, Blacks after 1877 were in essentially the same situation as in 1865, when slavery was formally ended. With all the violence they had seen, they must have wondered indeed whether their gains had been worth the trouble. Yet their considerable achievements should be recognized: Former slaves had participated in government in high levels, including the United States Congress. The new constitutions they had helped write were more progressive than many in the North. Many former slaves had managed to become landowners, had voted in elections and pursued educational goals. They had become part of the body politick. But for decades, the hopes of most Southern blacks were not realized.

Reconstruction Reversed: Redeemers in Power

The Clock is Turned Back. Historian Page Smith writes that the Compromise of 1877 which ended Reconstruction "was also a death sentence for the hopes of southern blacks." Feeling that the North under the radical Republicans in Congress had sought to impose "black rule" on the South, post Reconstruction in the South set about restoring white supremacy. Their assault on Black rights proceeded on both political and economic ground. Once federal troops left the South and the Federal government had turned to other matters, all the advances that had been made for black people during the reconstruction period slowly began to unravel. The Southern governments that took over were dominated by conservative Democrats known as “Redeemers.” Their purpose was to disenfranchise Republicans, black or white, and restore what they viewed as the proper order of things, namely, a society based on white supremacy. The Republican Party soon ceased to exist as a viable political force in the former Confederate states, and Democrats ruled the South into the late twentieth century.

(See Page Smith, The Rise of Industrial America: A People's History of the Post-Reconstruction Era, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984, pp. 615-640, passim.)

All across the South in the years between 1880 and 1900 blacks who attempted to exercise their electoral franchise were harassed, intimidated, and even killed to prevent them from voting. Resolutions were passed by groups of white citizens, and editorials appeared in newspapers claiming that Blacks should be excluded from voting because of their political incompetence. Even a brief alliance between Blacks and poor white farmers during the rise of the Populists could not stem the tide of Black disenfranchisement. Some southern leaders took pride in their attempts to prevent Blacks from voting; one South Carolina leader even bragged of having shot blacks for attempting to vote. Black leaders courageous enough to fight the tide of discrimination were unable even through eloquent pleas for fairness to effect a change in the growing attitude of political discrimination.

As for social equality, during the last quarter of the 19th century, the Southern states passed many “Jim Crow” laws that resulted in segregated public schools and limited black access to public facilities, such as parks, restaurants and hotels. Segregation in the South soon spread to virtually all public entities. As noted above, the Sumner Civil Rights Act of 1875was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1883. The Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protected blacks from discrimination by state action, but not by individuals, thus making “Jim Crow” laws possible and legally acceptable. As a Richmond Times editorial stated, “God Almighty drew the color line and it cannot be obliterated. The Negro must stay on his side of the line, and the white man on his.”

As for social equality, during the last quarter of the 19th century, the Southern states passed many “Jim Crow” laws that resulted in segregated public schools and limited black access to public facilities, such as parks, restaurants and hotels. Segregation in the South soon spread to virtually all public entities. As noted above, the Sumner Civil Rights Act of 1875was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1883. The Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protected blacks from discrimination by state action, but not by individuals, thus making “Jim Crow” laws possible and legally acceptable. As a Richmond Times editorial stated, “God Almighty drew the color line and it cannot be obliterated. The Negro must stay on his side of the line, and the white man on his.”

At the same time, the United States Congress was also tired of dealing with Reconstruction because of other political issues that needed attention. The country had undergone a long-lasting financial recession beginning in 1873; Custer's men were wiped out at Little Bighorn in 1876; the first transcontinental railroad had been completed in 1869, but labor discontent was rising; and immigrants were pouring into the country at an ever-increasing rate. Thus the problems of the South had become something of a distraction. Social equality for Blacks was nonexistent, and Congress seemed unconcerned.

Because of the impact of the Ku Klux Klan and a general high level of corruption that attended the democratic process in all parts of America, the electoral process, including presidential elections, was rough at best. In the North political machines told their voters to “vote early and often”; in the South the Reconstruction governments were also touched by corruption, and both black and white leaders found themselves unequal to the task of furthering the rights of freedmen without further enraging whites.

Washington & DuBois. Along with voting restrictions, strenuous attempts were made to limit black economic rights. Although Blacks had demonstrated their ability to work in a variety of traits such as blacksmithing, carpentry and stone-masonry, discriminatory hiring practices and boycotting of black tradesmen tended to limit Blacks to tenant farming and other menial positions. Booker T. Washington fought that trend as he rose to leadership of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. To his fellow African-Americans he preached a doctrine of hard work, clean living and a focus upon the ordinary skills of life that people needed on the road to good health and prosperity. He said, “our knowledge must be harnessed to the things of real life.”

As leader of Tuskegee, Washington saw to it that training focused on skills that would serve Blacks in commercial areas. In his Atlanta Exposition address he said, “there is as much dignity and tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top.” Washington's approach was roundly criticized by other black leaders. Black leaders such as John Hope argued that blacks should indeed strive for full equality, political and social, as well as economic.

The best-known of Washington's critics was W.E.B. Du Bois. Raised in the North, he was shocked when he first experienced discrimination in the South. Joining the faculty at Atlanta University, the boys began to study social conditions of blacks up close. He began a campaign against “ignorance and its child, stupidity.” He called for intelligent Blacks to provide leadership in developing the intellectual capacities of all African-Americans, calling those of superior intellect the Talented Tenth. DuBois’s Souls of Black Folk is an eloquent exposition of the cause of Blacks. He felt that Washington's approach ignored the realities of American political life, that giving up social and political equality in exchange for commercial excess was ultimately a road to failure.

Facing a wall of white prejudice and discrimination, Booker Washington opted to strive for what was achievable, perhaps at the cost of what was more desirable. Criticism of Washington's approach has continued into modern times, but as Page Smith notes, “much of the present day discussion about Washington's educational and racial philosophy fails to take into account that he had no alternative.” ”Admirable as DuBois’s goals were, he was also limited in his vision. A Harvard educated intellectual, he failed to fully appreciate the conditions facing thousands of blacks not only in the South but across America.

One response to the conditions in the South was the beginning of a mass exodus from the South by blacks into the Midwest and to the cities in the northern parts of the United States. As the hopes of the Reconstruction era began to be dashed, thousands of blacks began to realize that their chances for a decent and successful life would be greatly enhanced by moving to parts of the country where discrimination was less rampant. In 1879 and 1880 a group of Blacks headed for Kansas, believing that conditions in the state where John Brown was still famous might be good for them. They became known as the Exodusters. Although that movement was short lived, later migrations to Oklahoma and other regions of the Old West by Blacks continued. Early in the 20th century the Black “great migration” to northern cities such as Chicago, Pittsburgh and New York involved millions. For example, between 1910 and 1930, the African-American population of Detroit grew from 6,000 to 120,000.

|