The Wartime Conferences: Diplomacy in World War II

Copyright © 2010, Henry J. Sage

“If Hitler invaded hell, I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.” –Sir Winston Churchill

The combined military might of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and the militarist Japanese Empire required the full cooperation of Allied leaders who, in other times and in other circumstances, might have had difficulty agreeing on what to have for lunch. The powers fighting against the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis—the United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China—conducted a series of high-level meetings to establish the overall policies and strategies for the conduct of the war. The war created by Hitler, Mussolini and Japanese Prime Minister General Hideki Tojo meant that Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of China, the Soviet Union's Premier Josef Stalin, England's Winston Churchill, France's Charles de Gaulle, and President Franklin Roosevelt had to share and agree upon ideas, not only of how the war should be fought, but how the world might be shaped once the war was over.

Chiang Kai-shek was worried about the Communist movement in his country, which would lead to the triumph of Mao Tse Tung's Communist Party in 1949. The Japanese occupation of large regions of Southeast Asia would cause additional political problems in the postwar era, including those in Vietnam, historically part of what was known as French Indochina. In Europe, France's Charles de Gaulle, who represented the Free French forces opposed to the collaborationist Vichy French government under Marshal Henry Pétain, concerned himself with issues that would affect postwar France, sometimes causing him to clash with other allied leaders, including General Eisenhower. For example, General Eisenhower had decided to bypass Paris in his advance toward Germany, feeling that the city had no military significance, but De Gaulle would not hear of it; Paris was liberated in August, 1945, about two months after D-Day.

There is no question that the Soviet Union bore the brunt of Germany's military might, suffering some 20 million casualties during the course of the war. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was unquestionably grateful for the assistance of the United States in supplying his country with much needed military supplies—everything from railroad locomotives to tanks, to airplanes, trucks and rubber boots—but he never lost sight of the ultimate goal of Soviet Communism, which was world domination. Winston Churchill understood that collaborating with Josef Stalin was to a certain extent making a pact with the devil. Yet, as he famously said, if Hitler had invaded the nether regions, he would have been prepared to make a pact even with the devil himself.

Roosevelt and Churchill were undoubtedly the closest of the Allied leaders both in temperament and in their vision of the way they saw the postwar world. Nevertheless, their war aims often clashed, and although the combined Chiefs of Staff which operated both in Washington and London were able to sort out many of the joint military issues, disagreements over the time and location of attacks, strategic bombing targets and other matters kept the tension levels high throughout most of the war. Top-level meetings were necessary to sort out policies.

The major issues addressed at these top-level meetings included the time and location of the Anglo-American invasion of the continent of Europe. In order to relieve pressure on the bleeding Soviet army, Marshal Stalin pushed for the earliest possible opening of the Western Front. But control of the seas, especially the English Channel, the air lanes over the European coast, and the production of landing craft and other support ships and equipment prevented the Allies from committing to the invasion until mid-1944. An additional issue was the terms of surrender which would be accepted from Germany and Japan, assuming that a military victory could be achieved. The term “unconditional surrender” was first discussed secretly at Casablanca, as both Churchill and Roosevelt agreed that Germany should understand with absolute clarity that it had lost the war. Eventually the policy was applied to both Germany and Japan.

The meetings began in 1941 when Prime Minister Churchill and President Franklin Roosevelt met on the British warship Prince of Wales in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, and agreed upon the Atlantic Charter. The two leaders quickly established a rapport and agreed on broad war aims such as self-determination of all people in their governments, free trade, fair labor and economic policies and permanent peace arrangements guaranteeing freedom of travel on the high seas. The goals were not unlike Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, not surprising as Roosevelt had spent eight years in the Wilson government.

Following Pearl Harbor Churchill and Roosevelt conferred frequently. Churchill made frequent visits to the White House where he and the president would spend days conferring about policy while the American and British and joint staffs worked on details.

The Casablanca Conference. By early 1943 it was necessary to refine the major goals for the war. President Roosevelt traveled to Casablanca, Morocco, where he met with Prime Minister Churchill and Charles de Gaulle of France. Perhaps the most important decision regarding war objectives was reached at Casablanca when the Allies decided to insist upon on unconditional surrender by the Axis powers. They further agreed that the next step in the assault on Germany would be the invasion of Sicily and Italy, and they agreed to assist the Soviet Union by all possible means.

The issue of unconditional surrender vis-à-vis Japan was especially complex in that the position of the Emperor of Japan, who was considered a divine figure, would have to be considered. Concerns over that issue arose late in the war as President Truman was contemplating use of the newly invented atomic bomb. The entry of the Soviet Union into the war against Japan was also an issue that the leaders visited more than once. Stalin argued that Russia had her hands more than full with Germany and could not enter the war against Japan until after Germany had been defeated. He promised at Yalta that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan three months after Germany's surrender, which occurred on May 8, 1945.

Cairo and Tehran. In November 1943 the President traveled again, this time to Cairo, where he met with Prime Minister Churchill and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China. In Cairo the three leaders reaffirmed their decision to continue to apply military force to Japan until Japan surrendered unconditionally. They also agreed that Japan was to return all occupied territories gained from World War I and that Korea should become free and independent. Following the Cairo conference the president moved on to Tehran, Iran, with Prime Minister Churchill where they met with Joseph Stalin. At the Tehran conference the major topic of discussion was the strategy for achieving the final defeat of Nazi Germany and the opening of the second front in Europe, for which Stalin continued to push vigorously. The Big Three also promised economic assistance to Iran.

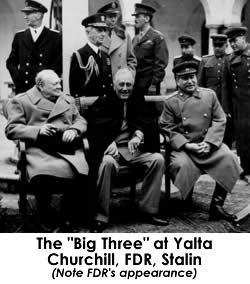

The Yalta Conference. The next major big three conference took place at Yalta in the Crimea in February, 1945. By that time Roosevelt's health was failing, and the long trip put him under considerable strain. It was clear to the gentlemen gathered in Yalta that the war against Germany was nearing a successful conclusion, so postwar issues rose to the fore. Premier Stalin wanted to establish a Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe while Churchill and Roosevelt pushed for free and democratic elections in that part of the world. Fear of the spread of Communism in the postwar world lay behind the concerns of Churchill and Roosevelt.

The Yalta Conference. The next major big three conference took place at Yalta in the Crimea in February, 1945. By that time Roosevelt's health was failing, and the long trip put him under considerable strain. It was clear to the gentlemen gathered in Yalta that the war against Germany was nearing a successful conclusion, so postwar issues rose to the fore. Premier Stalin wanted to establish a Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe while Churchill and Roosevelt pushed for free and democratic elections in that part of the world. Fear of the spread of Communism in the postwar world lay behind the concerns of Churchill and Roosevelt.

Stalin made it clear that he would control Poland because it had historically served as a corridor for attacks against Russia. Roosevelt pushed on Stalin to promise to enter the war against Japan once Germany was subdued, and he also urged the Soviet premier to join the United Nations. There was talk of free elections in Eastern Europe, and Stalin did sign an agreement on that general topic, but it was only a statement of principle.

The decisions and agreements made at Yalta remained controversial for years afterward, and much was blamed on FDR’s poor health. Roosevelt does seem to have been too willing to believe that Stalin was a reasonable man who wanted peace, but it is unlikely that a hard line in Yalta would have produced significantly different results in the long run.

The Potsdam Conference. The final wartime meeting took place at Potsdam outside Berlin in July 1945 after Germany had capitulated. Winston Churchill was replaced by Clement Attlee, the newly elected British Prime Minister during the conference. At Potsdam President Truman informed Premier Stalin of a powerful new weapon, the atomic bomb, about which Stalin already seemed to be informed, as indeed he was. Stalin confirmed his commitment to enter the war against Japan within three months of Germany's surrender, which reassured Truman, although there is speculation that the decision to drop the atomic bomb was aided by the hope that by preventing an invasion of Japan Russia could be kept out of Japan.

This very brief overview of the wartime conferences only suggests the complexity of the diplomatic efforts put forth by all parties. Many additional to meetings between top and high-level officials took place throughout the war, and a wide range of complex issues had to be dealt with. It can be stated with reasonable certainty that the overriding goal of defeating Germany and Japan was never lost from sight; the issues concerned methods, timing, priorities, and most of the controversy arose over the disposition of the warring nations once the piece had been secured.

Those postwar issues had less to do with the actual conduct of the war, which turned out successfully, though it was very costly, than with the concessions made to Stalin, especially at Yalta. The agreements reached were seen by many to have been shortsighted, in that they enabled Stalin to create what Churchill later called the “Iron Curtain” by seizing control of most of Eastern Europe, including part of Germany. The wartime conferences are a subject of their own and deserve the attention of anyone interested in the topic of wartime diplomacy.

| World War II Home | Updated May 8, 2017 |