SUMMARY. The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when South Carolina troops fired on the federal Fort Sumter in Charleston. That momentous event, however, was but one important milestone in the conflict over slavery in America. It is probably safe to say that the struggle began in 1619 when the first slaves were offloaded from a Spanish ship in the Jamestown, Virginia colony. The fate of those early slaves remains obscure, but we do know that within 50 years, permanent lifetime slavery for African-Americans brought to America was established. Protests against slavery began in the late 1600s when the Quaker church condemned slavery, yet the practice continued through the American Revolution. After 1776, as many of the states considered the meaning of Jefferson's words that “all men are created equal,” however, the elimination of slavery began in the North. Slavery was also prohibited in territories belonging to the new nation under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

After 1800 the cotton economy in the South gave new life to the institution of slavery as slave labor became ever more valuable. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 up held the balance between slave states and free states while prohibiting slavery north of the 36°30' parallel. That compromise limited debate at the national level for 30 years. By 1830, however, the growing abolitionist movement gave pause to defenders of slavery in the southern states, and they sought ways to inhibit the federal power to outlaw the practice. The nullification crisis of 1832, ostensibly over tariffs, had a hidden agenda, namely, the ability of states to nullify federal laws that might be applied to slavery. When the tariff effort failed, it became apparent that the next logical defensive measure would be secession.

While discussion of the slavery issue in the United States Congress was muted by various gag laws, the conflict simply would not disappear. The accession of Texas prompted more debate over slavery, and when the annexation of Texas triggered war with Mexico, the resulting addition of a huge new block of territory in the Southwest opened the issue yet again. In anticipation of attempts to block slavery in the new Territories, delegates of southern states met in Nashville in 1850 to discuss secession. Although moderate voices prevailed, the idea of secession was now a distinct possibility, openly discussed. When the California gold rush made that territory ready for admission as a state, Congress was required to formally address the issue of slavery, thus instituting one of the great debates in American history, debate over the Compromise of 1850.

To this day, there are those who claim that the American Civil War was not about slavery. They say was about tariffs, or states' rights, or something to do with the industrial North and the agricultural South, or immigration patterns that differed significantly between the northern and southern states. That issue has been addressed in detail by historians, and it is safe to say that the consensus has concluded that without slavery, there would have been no Civil War. The documentary evidence to support that conclusion, including the Constitution of the Confederate States of America written in 1861, makes it clear that the purpose of secession, which triggered the war, had the purpose of preserving slavery in the South. And if the issue was states' rights, the South Carolina Ordinance of Secession shows clearly that South Carolina, the first southern state to secede, was on the opposite side of that issue.

States' Rights, Popular Sovereignty and Slavery

Causes of the Civil War: Myth and Reality

As mentioned above, although the causes of the Civil War are still debated, it is difficult to imagine the Civil War occurring without recognizing the impact slavery had on the difficulties between the North and the South. For a time the tariff and other issues divided North and South, but there is practically no mention of any of them in the secession documents or in the great debates of the 1850s. Some argue that it was an issue of states’ rights, but none of the secession documents argue their case on those grounds. Indeed, in the South Carolina Ordinance of Secession, the first to be adopted and a model for later ones, part of South Carolina's justification for secession is that Northern states had attempted to annul the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Those northern states were, in effect, exercising their states’ rights, but South Carolina did not approve of their action.

Many Americans nevertheless believe that the Civil War was only incidentally connected with slavery. That view is difficult to reconcile with the known facts based upon existing documents from the Civil War era. Virtually every major political issue of a controversial nature between 1850 and 1860 deals with the issue of slavery. Furthermore, the issue had been contentious since before the American Revolution.

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, there was much discussion of slavery that resulted in the so-called 3/5 Compromise. Since the institution of slavery was dying out in parts of the country during the Revolutionary era, it is understandable that the framers of the Constitution hoped that slavery would die a natural death. Slave owners such as a Washington, Jefferson and George Mason all understood  the dangers involved in the continuation of slavery in the nation. Indeed, during the Constitutional Convention, on August 22, 1787, George Mason made a speech in which he, in effect, predicted the Civil War because of slavery. As James Madison's notes recorded, Mason argued as follows during the debate on the slave trade:

the dangers involved in the continuation of slavery in the nation. Indeed, during the Constitutional Convention, on August 22, 1787, George Mason made a speech in which he, in effect, predicted the Civil War because of slavery. As James Madison's notes recorded, Mason argued as follows during the debate on the slave trade:

“The present question concerns not the importing States alone but the whole Union. The evil of having slaves was experienced during the late war. Had slaves been treated as they might have been by the Enemy, they would have proved dangerous instruments in their hands. … Maryland and Virginia he said had already prohibited the importation of slaves expressly. North Carolina had done the same in substance. All this would be in vain if South Carolina and Georgia be at liberty to import. The Western people are already calling out for slaves for their new lands, and will fill that Country with slaves if they can be got through South Carolina and Georgia. Slavery discourages arts and manufactures. The poor despise labor when performed by slaves. They prevent the immigration of Whites, who really enrich and strengthen a Country. They produce the most pernicious effect on manners. Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of heaven on a Country. As nations can not be rewarded or punished in the next world they must be in this. By an inevitable chain of causes and effects providence punishes national sins, by national calamities. He lamented that some of our Eastern brethren had from a lust of gain embarked in this nefarious traffic. As to the States being in possession of the Right to import, this was the case with many other rights, now to be properly given up. He held it essential in every point of view that the General Government should have power to prevent the increase of slavery. [Emphasis added]”

Because the creation of the Constitution was a supreme challenge, the founding fathers were not prepared to deal with the slavery issue more directly. The invention of the cotton gin and the booming Southern cotton industry which followed, further negated hopes for a gradual diminution of slavery in America. The Constitution did, however, permit Congress to ban the importation of slaves 20 years after adoption of the Constitution. That measure was carried out in 1808.

Although the Constitution gave the federal government the right to abolish the international slave trade, the government had no power to regulate or destroy the institution of slavery where it already existed. Nonetheless, Congress prevented the extension of slavery to certain territories in the Northwest Ordinance (which carried over to the period after the Constitution) and the Missouri Compromise of 1820. So long as both North and South had opportunities for expansion, compromise had been possible. Traditionally, slavery, where it existed, had been kept out of American politics. The result was that no practical program could be devised for its elimination in the Southern states. Until the 1850s, however, Congress was understood to have the power to set conditions under which territories could become states and to forbid slavery in new states.

The issue of the admission of Missouri to the Union in 1820 drew the attention of Congress to slavery again. Although attempts to eliminate slavery in the state failed, the Missouri Compromise allowed Missouri to come in as a slave state, with Maine entering as a free state at the same time, thus maintaining the balance between free states and slave states in the Senate. Slavery was prohibited north of the southern boundary of Missouri from that time forward. The restriction was agreeable to the South in part because the area north of Missouri was still known as the “great American desert.”

The abolition movement brought new attention to slavery beginning about 1830. When the moral issue of slavery was raised by men like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, further compromise became more difficult. Documents began to appear describing the brutal conditions of slavery. Nevertheless, abolitionism never achieved majority political status in the non-slave states. Since most Americans accepted the existence of slavery where it was legal (and constitutionally protected), the controversy between North and South focused on the issue of slavery in the territories.

The issue might have been resolved by extending the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific Ocean to cover the new territory added in the Mexican Cession. However, since the movement to prohibit slavery in the territories was stronger in 1850 than it had been in 1820, the political forces were unable to handle it  as smoothly as in 1820. Thus another sort of compromise was needed, one that shifted responsibility from the national government to the territories themselves. That novel concept was known as “popular sovereignty”—letting the people in the new territories decide for themselves whether to have slavery.

as smoothly as in 1820. Thus another sort of compromise was needed, one that shifted responsibility from the national government to the territories themselves. That novel concept was known as “popular sovereignty”—letting the people in the new territories decide for themselves whether to have slavery.

The idea of popular sovereignty had two things going for it. First, it seemed democratic. Why not let the people decide for themselves whether or not they want slavery? (Of course participation in that decision was never extended to the slave population.) Second, it was compatible with the notion of “states’ rights.” The doctrine contained a major flaw, however; it ignored the concerns of those who tolerated slavery only on the assumption, as Lincoln and others put it, that slavery “was in the course of ultimate extinction.” As the abolition and free soil advocates saw it, allowing slavery to go into the territories was certain to postpone that day.

The net result of the popular sovereignty approach was that the federal government, in attempting to evade responsibility by shifting it to the people of the territories themselves, merely heightened the crisis. By 1850 slavery had become a “federal case,” and despite the best efforts of compromisers like Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas, the tactic of popular sovereignty backfired. The country drifted closer to war.

The Constitution gave the federal government the right to abolish the international slave trade, but no power to regulate or destroy the institution of slavery where it already existed. Nonetheless, Congress had prevented the extension of slavery to certain territories in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. So long as both the free North and the slave South had some opportunities for expansion, compromise had been possible. Traditionally, existing slavery had been kept out of American politics, with the result that no practical program could be devised for its elimination in the southern states. Congress, however, had the power to set the conditions under which territories became states and to forbid slavery in new states.

In the 1840s, as the result of expansion, Congress faced the problem of determining the status of slavery in the territories taken from Mexico. While prosperity came from territorial expansion, sectional harmony did not. When the United States gained 500,000 square miles of new land in 1848 (over 1,000,000 counting Texas), the nation again had to decide whether slavery was to be allowed in the territories of the United States. The Constitution prevented federal control of slavery in states where it existed, but gave Congress control over the territories. That was where slavery’s opponents could combat the institution they deplored.

Beginning with the Great Land Ordinances of the 1780s the United States had tried to govern its territories in a way which would be consistent with American practice (which unfortunately included neglect of the rights of the indigenous populations of Indians and others.) The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which covered five future states, established federal territorial policy. As was discussed earlier, had that policy been extended to future territories, a great deal of grief might have been spared, for the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery in the Old Northwest.

The acquisition of new territory from France, the Louisiana Purchase, precipitated a crisis when the subject of slavery in that territory came to a head over the issue of the admission of Missouri. The Missouri Compromise in 1820 resolved the issue for the time, but only postponed the crisis—as Jefferson and many others recognized at the time. The issue reemerged in 1848 after the Mexican-American War, and another crisis over the handling of slavery in the territories developed. To begin with, absent laws (such as the Northwest Ordinance) prohibiting slavery, nothing prevented slave owners from taking their "property" into the territories. Thus when the population became large enough for the territory to begin thinking of statehood, slavery had to be considered when the people in the territories wrote their constitutions and applied to Congress for admission. Since those state constitutions were an essential step on the road to statehood, Congress had some control over the process through approval of the proposed constitutions. Thus the issue became a national one and not one of states’ (or territorial) rights.

Since abolitionism never reached majority status in the non-slave states, and since most Americans accepted the existence of slavery where it was legal (and constitutionally protected), the chief controversy between North and South became the issue of slavery in the territories. The issue might have been resolved by extending the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific to cover the new territory, but since the movement to prohibit slavery in the territories was much stronger in 1850 than it had been in 1820, the political forces were unable handle it as smoothly as in 1820. Thus another sort of compromise was needed, one that shifted responsibility from the national government to the territories themselves. That novel concept was known as "popular sovereignty."

The idea of popular sovereignty had two things going for it. First, it seemed democratic. Why not let the people decide for themselves whether or not they want slavery? (Of course participation in that decision was never extended to the slave population.) Second, it seemed acceptable to Americans for whom "states’ rights" was the condition on which they continued to tolerate federal government control over local issues. The doctrine contained a major flaw, however, in that it ignored the concerns of Americans who continued to accept slavery only on the assumption, as Lincoln and others put it, that it "was in the course of ultimate extinction." Allowing slavery to go into the territories was certain, as the abolition and free soil advocates saw it, to postpone that day.

The net result of popular sovereignty was that the federal government, in attempting to evade responsibility by shifting it to the people of the territories themselves, merely heightened the crisis. For a time some politicians comforted themselves with the notion that slavery could not exist in any territory absent legislation to support it. (Douglas’s "Freeport Doctrine," for example.) Such claims satisfied neither supporters nor opponents of slavery. By 1850 slavery had become a "federal case," and despite the best efforts of compromisers like Clay and Douglas, the tactic of popular sovereignty backfired, and the country drifted closer to war.

Following the annexation of Texas as a slave state, the United States declared war against Mexico in 1846. Realizing that the war might bring additional new territory to the United States, antislavery groups wanted to make sure that slavery would not expand because of American victory. Congressman David Wilmot opened the debate by introducing a bill in Congress that would have banned all African-Americans, slave or free, from whatever land the United States took from Mexico, thus preserving the area for white small farmers.

The so-called “Wilmot Proviso” passed the House of Representatives but failed in the Senate, where John C. Calhoun argued that Congress had no right to bar slavery from any territory. Others tried to find compromise ground between Wilmot and Calhoun. Polk suggested extending the 36-30 line of the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific coast. In 1848 Lewis Cass proposed to settle the issue by "popular sovereignty"—organizing the territories without mention of slavery and letting local settlers decide whether theirs would be a free or slave territory. It seemed a democratic way to solve the problem and it got Congress off the hook. This blend of racism and antislavery won great support in the North; though it was debated frequently, however, it never passed. The battle over the Proviso foreshadowed an even more urgent controversy once the peace treaty with Mexico was signed.

Popular Sovereignty and the Election of 1848

The North rejected the extension of the Missouri Compromise line as too beneficial to southern interests, but many supported popular sovereignty. The Democrats, who almost split North and South over slavery, nominated Lewis Cass, who urged "popular sovereignty." Webster was the natural choice of Whigs, but the war hero was too appealing. Zachary Taylor avoided taking a stand but promised no executive interference with congressional legislation. Discontented Democrats (called "barnburners") walked out and joined with old members of the Liberty Party to form the Free-Soil Party, which nominated Martin Van Buren—who favored the Wilmot Proviso,—and Charles Francis Adams. Popular sovereignty found support among antislavery forces, who assumed that the territorial settlers would have a chance to prohibit slavery before it could get established, but it was unacceptable to those who wanted a definite limit placed on the expansion of slavery. President Polk’s fears were realized when Taylor won with a minority of the popular vote.

The California Gold Rush

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, thousands of Americans began flocking to California’s gold fields in 1848-1849, creating demands for a territorial government. There were few slaves in California, though more than in New Mexico and Utah combined. But slavery was not an admission issue, though California passed “sojourner” laws that allowed slaveholders to bring slaves and keep them for a time. Still, the question of slavery in the territories had to be faced; California merely precipitated the crisis. Taylor proposed to settle the controversy by admitting California and New Mexico as states without the prior organization of a territorial government, even though New Mexico had too few people to be a state. The white South reacted angrily. Planters objected that they had not yet had time to settle the new territories, which would certainly ban slavery if they immediately became states. A convention of the Southern states was called to meet at Nashville, perhaps to declare secession. Only nine states sent representatives, and although nothing was formally decided, the Nashville Convention forebode greater problems.

No one questioned the right of a state to be free or slave. Californians submitted an antislavery constitution with their request to admission. Southerners were outraged because the admission of California would give the free states a majority and control of the Senate. Once again, Henry Clay rose to offer a compromise. He proposed the admission of California as a free state; the remainder of the cession territory be organized without mention of slavery; a Texas-New Mexico boundary controversy be settled in New Mexico’s favor, but Texas be compensated with a federal assumption of its state debt; the slave trade (but not slavery) be abolished in Washington, D.C.; and a more stringent fugitive slave law be enacted and vigorously enforced. Although Taylor resisted the compromise until his death, his successor Millard Fillmore supported what became known as the Compromise of 1850.

THE COMPROMISE OF 1850 -- The Last Best Hope

After the death of Calhoun and departure of Webster and Clay, young Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois took over. Breaking the compromise down into separate measures, which allowed members to vote against what they didn’t like and for the rest, Douglas brought the seven-month-long debate to a successful conclusion. Congress adopted each of Clay's proposals as a separate measure and changed them slightly—for example, the Democrats extended popular sovereignty to the Utah territory. The Compromise admitted California as a free state, organized the territories of New Mexico and Utah on the basis of popular sovereignty, retracted the borders of Texas in return for assumption of the state's debt, and abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The most controversial provision created a strong Fugitive Slave Law, denying suspected runaways any rights of self-defense, and requiring Northerners to help enforce slavery. The South accepted the Compromise of 1850 as conclusive and backed away from threats of secession. In the North, the Democratic party gained popularity by taking credit for the compromise, and the Whigs found it necessary to cease their criticism of it.

1850 Compromise: The History

The debate over the compromise of 1850 has been called the last great Clay, Calhoun and Webster performance. Henry Clay was back in the Senate with his two fellow members of the "Great Triumvirate" and he began a debate by introducing various resolutions designed to achieve a compromise. Issue the three  men made passionate, memorable speeches in defense of their positions. John C Calhoun was the spokesman for southern, proslavery advocates. Aging like his two colleagues, Calhoun was ill during the debates, and his speeches were delivered by Senator Mason of Virginia a grandson of George Mason. Calhoun's major point was an argument for federal guarantees for slavery in the territories.

men made passionate, memorable speeches in defense of their positions. John C Calhoun was the spokesman for southern, proslavery advocates. Aging like his two colleagues, Calhoun was ill during the debates, and his speeches were delivered by Senator Mason of Virginia a grandson of George Mason. Calhoun's major point was an argument for federal guarantees for slavery in the territories.

Henry Clay, although a slaveholder, was from Kentucky, a border state where the defense of slavery was a far less vital matter than in the deeper South. Daniel Webster from New England was opposed to slavery, but was even more strongly opposed to the idea of secession, declaring that the notion of a "peaceable secession" was impossible. The three Berry and orators also heard powerful rhetoric from abolitionist Senator William Seward of New York who declared that there was a "higher law" than the Constitution that bound him to oppose the expansion of slavery. The idea of the higher law was meant as a moral argument that overrode the constitutional issue. Because there were portions of the proposed law that were unacceptable to significant blocs of voters, after months of debate tea law had not passed.

The deaths of President Zachary Taylor led to the breaking of the deadlock over the issue of slavery in the new territory that including California. President Fillmore asked Daniel Webster to return his former position as Secretary of State. Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, later known as the "Little giant," assume leadership of the debate and, realizing that the measure could not pass as designed, broke it into five separate bills and guided each one through Congress separately. In that matter to people who were bitterly opposed to certain portions of the proposed compromise could vote against them, but the combined negatives were not sufficient to block the five separate bills. After seven months of debate the five laws that made up the Compromise of 1850 provided for the following:

1. California enters as free state; few of those participating in the gold rush were anxious to share their find with slaves, so there were few in the territory.

2. The Texas-New Mexico boundary was adjusted adjusted; New Mexico Territory was allowed to settle the slavery issue on the basis of popular sovereignty. Texas gave up its claims to New Mexico for $10 million.

3. The Utah territory was also organized on the basis of popular sovereignty.

4. The fugitive slave act of 1793 was superseded by a new, much tougher act. It gave federal jurisdiction to the return of runaway slaves. The affidavit of a claim slave owner was sufficient for the issue of a warrant. Free blacks had no voice in court decisions regarding the return of slaves. Stiff penalties were adjudged for interference with the law, and the fees judges received were higher if the slaves were redeemed returnable.

5. As a concession to antislavery interests, the slave trade was abolished and the District of Columbia, though slavery itself was still permitted in the nation's capital.

The immediate result of the 1850 compromise was euphoric acceptance. Many Americans considered the legislation a "final solution" to the slavery issue. Radical northern abolitionists, however, were not satisfied that slavery might still continue under the compromise laws. In the end the compromise was bound not to be a permanent solution as both sides rejected some of the other's conditions; everybody was opposed to at least part of it. Yet the end of the bitter debate did result in the reconciliation of some politicians would become estranged over the issue. A relative period of peace and harmony reigned in the United States Congress, though it was not to last very long.

The new 1850 fugitive slave law struck fear in the hearts of northern blacks and encouraged more southerners to try to recover escaped slaves. Once the law went into effect slaves who had lived in the North as free men for long periods of time suddenly found themselves liable to being returned to their former owners. Abolitionists often interfered with the enforcement of the law, and such efforts exacerbated sectional feelings. The sight of blacks being carried off to slavery outraged northerners, and southerners resented the northerners' refusal to obey the law. Some of the northern states passed personal liberty lowers to protect free blacks, but the Fugitive Slave Law forced many northerners to experience the heartlessness of slavery.

One example of the trouble caused by the Fugitive Slave Act took place in Christiana, Pennsylvania in 1851. Fugitive slaves from nearby Maryland escaped to a farm where a Freeman protected runaways. The slave owner pursued the fugitives and was killed in a gun battle. The case was tried in a federal court and no one was convicted, but the Christiana incident, sometimes referred to as the "first shots fired in the Civil War," cause further bitterness, both sides.

Although some southerners objected to certain provisions of 1850 compromise, because the law had been duly passed by Congress they were obliged to obey it or look toward the radical action of secession. The South then divided into two camps, those opposed to and those favoring secession. Those two sides would carry their arguments forward throughout the 1850s.

THE GREAT DEBATE OVER THE COMPROMISE OF 1850

In the weeks of Senatorial debate which preceded the enactment of the Compromise of 1850 a range of attitudes was expressed. Clay took the lead early in speaking for the resolutions he had introduced The Great Compromiser advised the North against insisting on the terms of the Wilmot Proviso and the South against thinking seriously of disunion. Calhoun, who was dying, asked Senator James M. Mason of Virginia to read his gloomy speech for him. After explaining why the “bonds of sentiment” between North and South had been progressively weakened, Calhoun went on to say how he thought the Union could be saved. His words offered little real hope. Three days later, he was followed by Daniel Webster, who agreed with Clay that there could be no peaceable secession. Webster’s attempt to restrain Northern extremists brought him abuse from anti-slavery men in his own section where formerly he had been so admired. Extreme views were expressed on both sides, but the passage of the compromise measures showed that the moderate spirit of Clay and Webster was still dominant

POLITICAL UPHEAVAL, 1852–1856

The Compromise of 1850 robbed the political parties of distinctive appeals and contributed to voter apathy and disenchantment. Although a colorless candidate, Democrat Franklin Pierce won the election of 1852 over Winfield Scott, the candidate of a Whig party which was on the verge of collapse from internal divisions. Once the Compromise of 1850 seemed to have settled the territorial controversy, Whigs and Democrats looked for new issues. The Democrats claimed credit for the nation's prosperity and promised to defend the compromise. Whigs, however, could find no popular issue and began to fight among themselves. Their candidate in 1852, Winfield Scott, lost in a landslide to Democrat Franklin Pierce, a colorless nonentity.

Pierce was known as a “doughface,” a northerner with souther sympathies, friendly to slavery. The Whigs were divided among those willing to compromise on territorial issues and the free soilers who opposed the extension of slavery by any means. The Republican Party, which came into existence during the Pierce administration, capitalized on the decline of the Whig Party, which was divided over slavery. In 1852 the tradition of small third parties continued with the Free Soil Party, who nominated John Hale, but their minimal support did not affect the election.

Free Soilers and Free Blacks. Personal liberty laws in North and Black laws in North and South create all kinds of restrictions on free Blacks in lower northern states: marriage, property, voting military service all restricted. Still, Fugitive Slave searches anger many northerners; interference angers Southerners. Movement for freedom was rarely a movement for equality for Blacks (see Lincoln); some political parties went farther than others: Free Soilers not as liberal as Liberty Party; Anti-slavery Whigs; few parties clean on objectives; most Free Soilers, Republicans were ambivalent on black rights.

Uncle Tom's Cabin. The publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin" also heightened sectional tensions. Like other northerners, the Fugitive Slave Law stirred Stowe's conscience, and her novel drove home the evils of slavery. While Stowe knew little about slavery and her picture of plantation life was distorted, her story had sympathetic characters and it was told with sensitivity. She was the first white American writer to look at slaves as people.

Uncle Tom's Cabin. The publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin" also heightened sectional tensions. Like other northerners, the Fugitive Slave Law stirred Stowe's conscience, and her novel drove home the evils of slavery. While Stowe knew little about slavery and her picture of plantation life was distorted, her story had sympathetic characters and it was told with sensitivity. She was the first white American writer to look at slaves as people.

The characters in the book include Tom, an intelligent, pious and courageous slave; the evil slave-owner Simon Legree; Augustine St. Claire, a kind owner; his sensitive daughter Eva who admires Tom; the runaway slave Eliza and her husband George and other provide a melodramatic but moving picture of “Life Among the Lowly”—which is the subtitle.

When Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, he is said to have remarked: "So you're the little lady who wrote the book that started this big war." Apocryphal or not, the book had a big impact on attitudes both North and South.

Franklin Pierce as President: The Distraction of Foreign Affairs

The “Young America Movement.” Foreign affairs offered a distraction from the growing sectional hostility. Sympathies were extended to European revolutionaries in revolt against autocratic governments. Some Americans dreamed of territorial acquisitions in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean as a means of spreading democracy. Young America was a volatile combination of altruistic motives and nationalist ideas, related to the concept of Manifest Destiny. Although the ideas bore little fruit in the 1850s, they did provide a diversion.

The need for better communication with California produced the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. It gave the United States and Britain joint control of any canal built through the isthmus. The appeal of an Isthmian Canal was strong, but the engineering required for such a feat was still several decades away.

In response to growing pressure from various southern quarters for the annexation of Cuba to offset the addition of California, American ministers to Great Britain, France and Spain met in Ostend, Belgium, and drafted a proposal outlining the purchase of Cuba from Spain. It proposed to purchase the island for $120 million suggested taking it by force if Spain refused. The Ostend Manifesto was published and drew immediate criticism on northerners, who saw it as a way to expand slavery.

One initiative that did bear fruit was the visit of Commodore Matthew C. Perry to Japan. In 1852 Perry sailed into Tokyo harbor with four American warships, presented Japanese officials a letter from President Fillmore proposing the initiation of formal relations between the United States and Japan. Perry returned to Japan two years later, and a formal trade and friendship agreement between the two nations was signed, thus beginning a long and sometimes troubled relationship between the two countries.

One other foreign affairs matter was settled in 1853. As plans were being drawn up for a transcontinental railroad, one possible route included territory to the south of the states of Arizona and New Mexico. Ambassador to Mexico James Gadsden negotiated the deal, and a swath of land from Las Cruces, New Mexico to Yuma, Arizona, that included what would become the city of Tucson, was purchased from Mexico. The purchase completed the territory that would become known as the "lower 48 states."

The Rise of Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant.”

Senator Stephen Douglas saw the needs of the nation in a broad perspective. He advocated territorial expansion and popular sovereignty. He opposed slavery, but did not find it morally repugnant. Generally, he did not think it was necessary for the nation to expend its energy on the slave issue. Both parties endorsed the Compromise of 1850 in the 1852 campaign, but the Whig party was disintegrating and proslavery southerners were coming to dominate the Democratic party.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act Raises a Storm

In 1854, Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas, anxious to expand American settlement and commerce across the northern plains while promoting his own presidential ambitions, pushed an act through Congress organizing the territories of Kansas and Nebraska on the basis of popular sovereignty. This repeal of the long-standing Missouri Compromise, along with publication of the "Ostend Manifesto" urging the United States acquisition of Cuba, convinced an increasing number of Northerners that Pierce's Democratic administration was dominated by pro-southern sympathizers, if not conspirators.

In 1854, Stephen Douglas introduced a bill to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territories. The area had a growing population and Douglas hoped to speed construction of a transcontinental railroad through the territory. Southerners balked because they wanted the railroad farther south and they feared Nebraska would become a free state. These areas were north of the Missouri Compromise line and had been off-limits to slavery since 1820, but Douglas proposed to apply popular sovereignty to them in an effort to get southern votes and avoid another controversy over territories. Douglas expected to revive the spirit of Manifest Destiny for the benefit of the Democratic party and for his own benefit when he ran for president in 1860. The South insisted, and Douglas agreed to add an explicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, thus provoking a storm of protest in the North, where it was felt that the South had broken a long-established agreement. The Whig party, unable to decide what position to take on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, disintegrated. The Democratic party suffered mass defections in the North. In the congressional elections of 1854, coalitions of "anti-Nebraska" candidates swept the North, and the Democrats became virtually the only political party in the South.

In the midst of this uproar, President Pierce made an effort to buy, or seize, Cuba from Spain, but northern anger at any further extension of slavery forced the president to drop the idea.

Nevertheless, the bill passed and the nation took a giant step toward disunion. Douglas introduces bill to organize the Kansas and Nebraska territories based on "popular sovereignty" or squatter principle. As it allowed for slavery in all new territories, it implicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise. Douglas not especially against slavery.

Douglas's rationale for his support of the bill had numerous aspects. For starters, he b believe strongly in the principle of self-government for the states. It is worth remembering here that until the amendments passed following the Civil War altered the relationship between the federal government and the states, the states still recalled the time when they consider themselves to be sovereign, independent nations under the Articles of Confederation. Second, and perhaps less honorable, Senator Douglas needed Southern support for the 1856 presidential election. Furthermore, he believed that geography itself would limit the extension of slavery by natural means, without federal government intervention. He strongly supported development of a transcontinental railroad, and he hoped that the terminus would be in Eastern Illinois. The bottom line of Douglas's position was most likely that he was a strong supporter of the principle of Manifest Destiny.

When finally passed the Kansas Nebraska act turned out to be a victory for the South. As a result, the Democrats lost most of their support in the north, and they became a southern party. The act repealed the Missouri Compromise (the Supreme Court would have the final say on that), which Northern Democrats published a document, the "Appeal of the Independent Democrats," which called the act a "gross violation of a sacred pledge." According to Horace Greeley, the Kansas Nebraska act created more abolitionists than William Lloyd Garrison had achieved in 30 years. In the eighteen fifty-four elections, the Democrats lost significantly because of the "disaster" of the Kansas Nebraska act. The Democrats lost most of their seats in the North and became a southern party.

In 1854 a former slave named Anthony Burns was captured in Boston under the provisions of the fugitive slave law. Mob attacks the prison where he was held and federal troops arrived. The supreme court upheld the primacy of the Fugitive Slave Law, calling it constitutional, and the state personal freedom laws did not in effect nullify the federal act.

An Appeal to Nativism: The Know-Nothing Episode

As the Whig Party collapsed, a new party, the Know-Nothings, or American Party, gained in popularity. Part adherents were identified as the Young America Movement. The Know-Nothing party especially appealed to evangelical Protestants, who opposed Catholics, largely because of the huge influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland triggered by the famine of the 1840s. The Know-Nothings—the name derived from their pledge to say "I know nothing" when asked about the policies of their party—also picked up support from former Whigs and Democrats disgusted with “politics as usual.” In 1854, the American party suddenly took political control of Massachusetts and spread rapidly across the nation. They generated anti-black feelings in the North, and their antislavery members defected to the newly formed Republican Party, which came into existence in 1854. In less than two years, the Know-Nothings collapsed for reasons that are still somewhat obscure. Most probably, Northerners worried less about immigration as it slowed down, and turned their attention to the slavery issue.

As the Whig Party collapsed, a new party, the Know-Nothings, or American Party, gained in popularity. Part adherents were identified as the Young America Movement. The Know-Nothing party especially appealed to evangelical Protestants, who opposed Catholics, largely because of the huge influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland triggered by the famine of the 1840s. The Know-Nothings—the name derived from their pledge to say "I know nothing" when asked about the policies of their party—also picked up support from former Whigs and Democrats disgusted with “politics as usual.” In 1854, the American party suddenly took political control of Massachusetts and spread rapidly across the nation. They generated anti-black feelings in the North, and their antislavery members defected to the newly formed Republican Party, which came into existence in 1854. In less than two years, the Know-Nothings collapsed for reasons that are still somewhat obscure. Most probably, Northerners worried less about immigration as it slowed down, and turned their attention to the slavery issue.

In 1855, a rising politician in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, who had served one term in the House of Representatives from1846 to 1848, was trying to keep his political career alive. Formerly a Whig, he joined the Republican Party and condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It's worth noting that when he ran for the Senate from Illinois in 1858 and for president in 1860, the issue most heavily debated was that of slavery in the territories. Attempts to remove slavery where it already existed would have to wait until after the Civil War. The country remained divided during the latter part of the 1850s; the wounds were becoming too deep to heal.

Kansas and the Rise of the Republicans

Formed in protest of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Republican party adopted a firm position opposing any further extension of slavery. Election fraud and violence in Kansas discredited the principle of popular sovereignty and strengthened Republican appeal in the North. The Republican party emerged as a coalition of former Whigs, Know-Nothings, Free-Soilers, and disenchanted, anti-slavery Democrats by emphasizing the sectional struggle and by appealing strictly to northern voters. Republicans promised to save the West as a preserve for white, small farmers.

Events in Kansas helped the Republicans. Abolitionists and proslavery forces raced into the territory to gain control of the territorial legislature. Proslavery forces won and passed laws that made it illegal even to criticize the institution of slavery. Very soon, however, those who favored free soil became the majority and set up a rival government. President Pierce recognized the proslavery legislature, while the Republicans attacked it as the tyrannical instrument of a minority. In Kansas, fighting broke out, and the Republicans used "Bleeding Kansas" to win more Northern voters.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act compelled former Whigs and antislavery northern Democrats to join new parties. The American, or Know Nothing Party, was founded by Nativists who blamed the recent flood of Catholic immigrants for rising crime, drunkenness, and poverty. The party enjoyed support in both the North and South because it was flexible on the slavery issue. More significant was the Republican party, a party dedicated to opposing the expansion of slavery. It was a sectional party that appealed to growing antislavery sentiments in the North. It was brought about by it's opposition to the Kansas Nebraska act, which he regarded as an outrage

Kansas became a testing ground for the ideal of popular sovereignty, which was at the heart of the politics of the slavery question. The Kansas Nebraska act was ambiguous about the time when the vote on slavery would be held, and who in Kansas would be permitted to vote. Both Northerners and Southerners tried to influence the situation. Groups of antislavery settlers came from New England to try to influence the vote against slavery. Proslavery Missourians crossed the border to vote in the Kansas elections. The result of the tension led to what was a near civil war in Kansas. The Franklin Pierce administration in Washington did nothing to help the situation, refusing to help restore order to the territory, although they did warn the border ruffians from Missouri to disperse. The Pottawatomie Massacre led by John Brown occurred on May 24 and 25. At last territorial governor Geary was able to obtain aid from federal troops, who dispersed the border ruffians. In all, 200 people were killed, and millions of dollars in property was destroyed.

The reaction in Congress to the situation in Kansas was sharp. Senator Sumner of Massachusetts insisted that Kansas be admitted as a free state. He gave a harsh speech called his “Crime Against Kansas” speech, a crude and offensive tirade that focused on a senator from South Carolina. Preston Brooks, a South Carolina congressman, came onto the Senate floor and thrashed Senator Sumner with a cane, injuring him severely. The senator was absent from the Senate for three years, and his vacant chair became a symbol for the antislavery forces in Congress. Kansas was finally admitted to the union as a free state in 1861.

THE ELECTION OF 1856

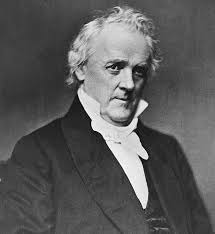

The 1856 United States presidential election reflected the bitter divisions in the country over the issue of slavery. Because of the unpopularity of the Civil War in Kansas, the Democratic Party rejected incumbent President Franklin Pierce and nominated James Buchanan (right), who had been out of the country as an ambassador during much of the furor over the Kansas-Nebraska issue and

The 1856 United States presidential election reflected the bitter divisions in the country over the issue of slavery. Because of the unpopularity of the Civil War in Kansas, the Democratic Party rejected incumbent President Franklin Pierce and nominated James Buchanan (right), who had been out of the country as an ambassador during much of the furor over the Kansas-Nebraska issue and  therefore had no record of comments on those events. The Republican Party, which had arisen out of the ashes of the Whig party, which had split over differences between its northern and southern components, nominated John C. Frémont, known as The Pathfinder because of his explorations over the Rocky Mountains and into California. His motto was “Free soil, free labor, free men, Fremont.” The American party, known as the Know Nothings because of their refusal to answer questions about their goals, nominated Millard Fillmore, who claim to be a compromise candidate.

therefore had no record of comments on those events. The Republican Party, which had arisen out of the ashes of the Whig party, which had split over differences between its northern and southern components, nominated John C. Frémont, known as The Pathfinder because of his explorations over the Rocky Mountains and into California. His motto was “Free soil, free labor, free men, Fremont.” The American party, known as the Know Nothings because of their refusal to answer questions about their goals, nominated Millard Fillmore, who claim to be a compromise candidate.

The Democrats supported popular sovereignty as a way of deciding on the status of slavery in the new states. Although Frémont did not call for abolition of slavery, he opposed the expansion into the territories. Buchanan warned that a Republican victory might lead to a civil war, which in fact happened in the 1860 election. For a fledgling party in their first national election, the Republicans did quite well, getting 33% of the vote and 114 electoral votes to Buchanan’s 45% and 174 electoral votes, although Frémont got very few votes in the South. Fillmore got 21% of the popular vote but only 8 electoral votes.

As an ardent Democrat, Buchanan had been favorable toward the south, what is the crisis over slavery grew sharper, he became more of a Unionist. But because he did little to address the divisions that were becoming extremely bitter, he is generally judged to be one of the worst American presidents. The nation was disintegrating around him, and he did little to try to stop it. When Lincoln was elected in 1860 and the southern states began succeeding, he did nothing, arguing that it was now Lincoln's problem, even though he would not be inaugurated until March.

| Civil War Home | Civil War Introduction | Path to War: 1850s | Civil War 1860-1862 |

| Decisive Year 1863 | Civil War 1864-1865 | Turning Points | Updated April 23, 2020 |