Copyright © 2012-2020 Henry J. Sage

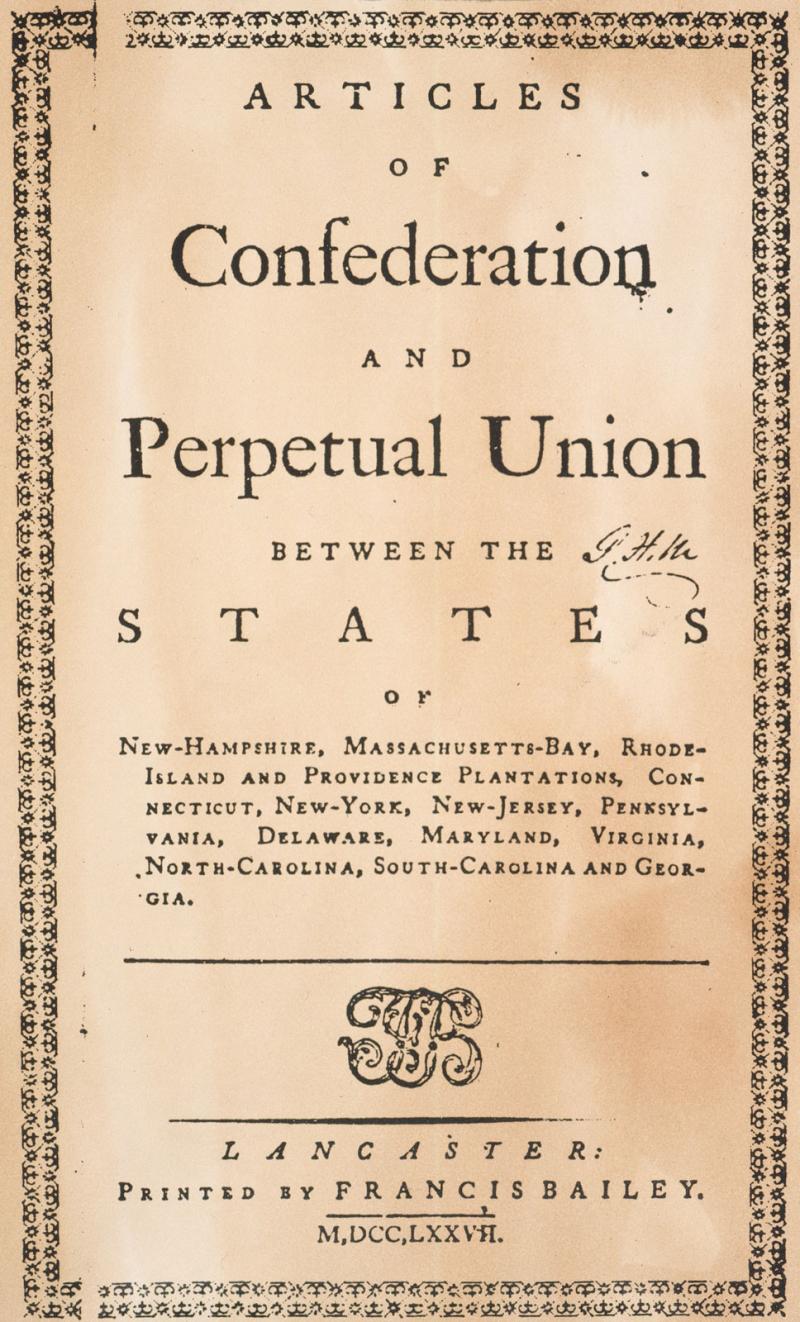

The American colonists had just fought a long and bitter war against a powerful centralized government; they were wary of creating another. The Second Continental Congress, which continued to function as the government of the new United States following the Declaration of Independence, drafted the Articles of Confederation in 1777. They had  organized themselves sufficiently to conduct the war, but even during the fighting, the states werejealous of their own prerogatives. For example, when Washington's army was marching from Boston to New York early in the campaign, a welcoming party from the government of Connecticut approached the advance units and inquired by whose permission this "foreign army" was being brought into Connecticut. United in the cause of war, they still were separate political units jealous of their independence. Preoccupied as Congress was with the conduct of the war, and occasionally having to move to avoid the British Army, they failed to find sufficient agreement on the Articles until they were ratified on March 1, 1781.

organized themselves sufficiently to conduct the war, but even during the fighting, the states werejealous of their own prerogatives. For example, when Washington's army was marching from Boston to New York early in the campaign, a welcoming party from the government of Connecticut approached the advance units and inquired by whose permission this "foreign army" was being brought into Connecticut. United in the cause of war, they still were separate political units jealous of their independence. Preoccupied as Congress was with the conduct of the war, and occasionally having to move to avoid the British Army, they failed to find sufficient agreement on the Articles until they were ratified on March 1, 1781.

It is worth noting that the issue of state sovereignty did not disappear. When South Carolina seceded in 1860, it declared in its succession document that "the state of South Carolina has resumed her position among the nations of the world, as a separate and independent state."

Under the Articles of Confederation, the states saw the themselves as independent republics; they had not yet created a nation. The American government under the Articles was, in effect, a "United Nations of North America," rather than the "United States" as a single nation. For decades the country was referred to in the plural: “The United States are preparing for an election.” Americans were in no hurry to create a powerful national government; only after several years of experiment did they begin to realize that thirteen “sovereign and independent republics” could not function as a nation without a strong central authority. The Articles provided for no executive authority in a president, no executive agencies, no common judiciary, no way to fund an Army or Navy, and a week fragmented foreign and trade policy. Although the Confederation Congress had a presiding officer, he had very little power and was by no means a chief executive. The Congress also had very little authority over the thirteen states, not being able to tax them nor to make any significant moves without unanimous consent of all the the states. In foreign affairs, which will be discussed further below, they had little leverage in dealing with other nations, for the European powers didn't know whether they were dealing with a nation or a random collection of 13 states. As a result, diplomatic progress was stymied.(In otherwords, governmentunder the articles was no way to run a railroad, much less a nation.)

It was only after several years of experiment that the states began to realize that they needed to make changes in order to conduct themselves as a nation ready to take part in world affairs. Led by Washington, Hamilton, Madison and others, they began to search for ways to improve their lot, and they are finally agreed on a convention, whose original purpose was to amend and revise the articles of Confederation. Any amendments, however, would've required unanimous consent of all 13 states. That would take time. Instead, when they got the Philadelphia, they simply chucked the articles and began writing a new document. We will get to the Constitution in due course, but meanwhile let's examine developments in the 1780s.

Republican Government. The most radical idea to come out of the American Revolution was the idea of republican government. To be called a republican in Europe in 1780 was something like being called an anarchist in later times, or a political extremist in today's world. The radical idea of republican government—government by the people—promised to profoundly change the relationship between men and women and their government. Some of those changes were subtle, but over the years their force was felt. Perhaps most important was the idea of virtue: Where did virtue reside in the political structure, and how could virtue be cultivated? In a state run by an aristocracy, a monarchy such as England's, the virtue—the goodness or quality or character—of the state was determined by the ruling class. Ordinary people had no real civic responsibility except to obey the laws. In a republic, from the Latin res publica, the people are responsible for the virtue of the state.

Other significant changes that came into focus during and after the Revolution included a new and more highly developed sense of equality, the idea that people should be judged by their worth rather than by their birthright, that being highly born is not a requisite for achievement or recognition. Those ideas developed slowly and unevenly, but the Revolution made such radical thinking possible. Some of those changes in attitude were translated into new laws and practices, such as mFurthermore, voting restrictions were whittled away, eliminating the requirements of property ownership or religious qualifications for voting. Although in the case of voting for electors in the presidential election, it was not until the 1820s that the people got a greater share of the vote.ore equitable treatment among all regions of the states. That concept would evolve over time and eventually the Supreme Court ruled that representation in Congress should be based upon the principle of one person one vote. That would take time, but the groundwork was laid. More liberal laws of inheritance, and greater religious freedom, including the separation of church and state, were other issues that were part of this revolutionary change.

The young American nation also had the extraordinary luxury of having about six years between the end of the fighting in America and the next outbreak of violence in Europe—the French Revolution—to find a new way to govern itself. If the French Revolution with all its turmoil had started earlier, or if the Americans had taken longer in getting around to writing their Constitution, things would certainly have turned out differently, quite possibly for the worse. Few nations have had such a broad and untrammeled opportunity to form a government under so little pressure.

More on the Theory of Republicanism

The States: Republicanism in Practice

Until independence was declared, the colonies continue to operate under their colonial charters. Massachusetts set an important precedent by drafting its constitution in a special convention called for that purpose in 1779. Soon thereafter constitution writing was going on in the rest of the states in special conventions, following the Massachusetts example, and by 1780, they all had adopted them. Those constitutions provided a practice arena for the writing of the United States Constitution. As John Adams, who drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, put it, "How glorious it was to be able to participate in the making of a government—few in history have had such an opportunity." The new state constitutions emphasized fundamental freedoms such as freedom of religion, speech, and the press. The office of governor was generally weak, and elected assemblies were given the most power. The state constitutions had to be ratified by a referendum of the people. Americans wanted written constitutions that would clearly define the rights of the people and the limits of government power. Their attitude reflected the American distrust of power, an American characteristic that continues to this day. While they incorporated parts of the British system into their new governments, being wise enough not to throw out the baby with the bath water, they still created radical new forms. (The state constitutions can all be viewed at Yale’s Avalon Project.)

In all of the states more of "the People's men" appeared in government. At the heart of the American experiment was the idea of equality. Ability, not birth, was what mattered. The new American aristocracy would be based on merit, not birth, men described as "stern and disinterested heroes." The theory of a born aristocracy was contradicted by what was called the surging individualism of American life. Americans were aware that the entire world was watching, with more than a little skepticism about whether this experiment in republican government could work. Many Europeans assumed that the American attempt to create a new form of government would fail and that America would become some sort of despotism or perhaps attach itself to one of the great nations of Europe.

Summary of Political Issues in the Early Federal Period

The Articles of Confederation were finally ratified in 1781: Maryland was slow to ratify, and unanimous consent was required. Until then the Second Continental Congress had been the de facto government. Congress had managed to win the Revolutionary War, but with difficulty and inefficiency. John Adams, for example, served on more than eighty committees. Wartime problems had been huge, and although much was accomplished, the confederation was cumbersome and inefficient. The colonies had never really gotten along very well, and now the states were jealous of federal power and of each other. Under the Articles, Congress had far less power than Parliament: There was no executive, and no courts were provided for. Government was operated by scores of committees. (Definition of a camel: a horse that was put together by a committee.)

In the 1780s, many Americans feared their Revolution could still fail if not grounded in a virtuous republican government, but ordinary folk, influenced by evangelicalism, expected progress founded on “goodness and not wealth.” They expected the Revolution to bring them greater liberty, a voice in government, and an end to special privilege. Others, fearing that too much liberty might lead to democratic excess, emphasized the need for order. In 1780, America might have been the most literate nation in the world, and if the citizens had not read John Locke, they were certainly aware in general of his principles. They understood that there was no such thing as absolute freedom of action, that to maintain liberty, freedom had to be circumscribed, but finding the balance between liberty and control by government was a difficult and delicate process. The bottom line issue was liberty versus order.

Republicanism—government by the people—was as radical for its time, as Marxism was later, although the concept had its origins in Greece and Rome. The concept spread throughout Europe in the 18th century. These ideas came together in revolutionary Americans to form one of the most coherent and powerful ideologies in the history of the world. Republicanism was a social as well as political construct, and the simplicity and plainness of American life were now seen as virtues. The evils of the Old World were seen as rooted in too much government, but in order for government to be minimized, the citizens had to be virtuous, patriotic, and willing to give to the mother country.

Property ownership was seen as requisite to participation in republican government because people needed to have a stake and be independent. Jefferson saw dependency as an evil—“it begets subservience and venality”—so he proposed that Virginia give fifty acres of land to every citizen who didn’t own that much. Because it was widely believed that the early state constitutions were flawed experiments in republican government, some Americans began to argue that a stronger central government was necessary.

As the need for a stronger central government became more apparent after 1783, the United States could easily have become a monarchy, with George Washington as George I of America. The American states first became independent republics, and the feeling was that viable republics were of necessity small.

With a successful war for independence behind them, the Americans still faced many difficulties in shaping a new republican government, having closed “but the first act of the great drama . . .” Much hard work remained to be done. Without the completion of the task of creating a viable government, the experiment still might have foundered.

A National Culture

The Cultural Declaration of Independence: By 1789 poems, plays, music, and art celebrated the Revolution and all things American. Noah Webster worked to produce the first American dictionary—the American language began to depart from English. American art stressed patriotic themes—portraits of  Washington and other revolutionary dignitaries abounded, and artists began to develop new styles. A fledgling American literary movement began with plays such as The Contrast, whose characters represented American virtues and corrupt old European ideas. American literature did not become highly evolved—that would have to wait for the Romantic Age under Emerson, Hawthorne, Whitman, and others—but the seeds were sown.

Washington and other revolutionary dignitaries abounded, and artists began to develop new styles. A fledgling American literary movement began with plays such as The Contrast, whose characters represented American virtues and corrupt old European ideas. American literature did not become highly evolved—that would have to wait for the Romantic Age under Emerson, Hawthorne, Whitman, and others—but the seeds were sown.

Mercy Otis Warren (left) was an important figure in the development of a national culture. She was a poet, a dramatist, and an early advocate for rebellion against the British policies instituted by the British governor of Massachusetts. Her History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution was the first full history of the revolution, and it is still available in print today. The sister of James Otis, she was a close friend of Abigail Adams, whose letters to her husband and to Thomas Jefferson are an important cultural artifact deriving from the revolutionary era.

The qualities that make virtuous citizens and therefore a virtuous state—decency, honesty, consideration of others, respect for law and order—are qualities that are first learned at home, generally at the mother’s knee. So in a very subtle way the role of motherhood, the job of raising virtuous citizens, became a public good. The concept was known as republican motherhood, and although women were still treated as second-class citizens for decades, when they began to make their case for full equality, they could and did point to seeds sown during the Revolution.

Although it took time there were reasons to expand women's rights. For example, women made important contributions to the Revolution, including fighting. Deborah Sampson served as a man from 1781 to 1783. Others did much to support the American armies—making bandages, and so on. Martha Washington did much to assist soldiers at Valley Forge. Women also demanded natural right of equality and contributed to the creation of a new society by raising children in households where the republican values of freedom and equality were daily practice. Women were more assertive in divorcing undesirable mates and in opening their own businesses, but were still denied their political and legal rights. Although women made some gains in education and law, society still defined them exclusively as homemakers, wives, and mothers.

Abigail Adams had said “Remember the ladies”—or they would foment their own revolution, which they eventually did. But even in the republican fervor of the post-revolutionary period, women got few new rights. The next major step in women's rights would come in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Declaration, which will be discussed in a future chapter.

(See the works of Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, who wrote the first full history of the American Revolution in1805, and other notable women of that era.)

Foreign Affairs: Diplomatic Humiliation

Congress had little power over the states and therefore over foreign policy. The result was that other nations either ignored the young United States or ran roughshod over their interests with little fear of retaliation. The British ignored certain provisions of the Paris agreement and kept troops on American soil long after the peace treaty was signed. Both the British and Spanish were feared to be stirring up Indians on the western frontiers, but Congress was powerless to do anything about it. In addition, the Royal Navy remained in American waters, a threat to American independence of action. In addition, the British refused to abandon their forts in the Northwest territory. The British were so contemptuous of American concerns that they failed even to send an envoy to the United States.

When Spain closed the port of New Orleans to American commerce in 1784, Congress sent John Jay to Madrid to achieve terms to open the Mississippi to Americans. Instead, Jay signed the Jay-Gardoqui Treaty, an agreement that ignored the problem of the Mississippi in exchange for commercial advantages benefiting the Northeast. Congress rejected the treaty, largely because of opposition by James Madison and James Monroe, and the issue smoldered for ten more years. Congress also claimed lands in the West still occupied by the British and Spaniards but could not forcefully challenge those nations for control of the land.

The American armed forces, except for state militias, over which Congress had little control, were for all practical purposes disbanded after the war. The U.S. Army numbered fewer than one hundred men in 1784. For good or ill, foreign affairs would come to dominate American public life and politics between 1790 and 1815—as Europe became steeped in the wars of the French Revolution and Empire. But even in the immediate postwar years, America carried little weight in the world despite having won the Revolutionary War. The issue of unpaid debts persisted, though some thought they should be renounced. George Mason is supposed to have said, "If we still owe those debts, then what were we fighting for?"

These diplomatic issues were understood by nationalists like Hamilton, and they were part of the reason for the creation of a new strong central government under the Constitution. But that would take time.

Commercial Issues: Foreign Trade

After the Revolution the American balance of trade was very negative, which led to a serious recession from 1784 to 1786. As Americans had been unable to trade with Great Britain during the war but still had an appetite for British goods, British imports to the United States expanded after the war, so money and  wealth were leaving the country. The young country also was critically short of hard currency, a situation exacerbated by the fact that cash was flowing overseas. Furthermore Congress had no taxing authority, and massive war debts, including promised pensions for soldiers, remained unpaid. It was clear that a strong central authority was needed to regulate trade—the Confederation government could not get a tariff bill through because of jealousy among the states. On the bright side—and there was not much there—new ports were now open and American ships could go anywhere they pleased, but without, of course, the protection of the Royal Navy. The vessel Empress of China sailed to the Far East in 1784–85, opening up trade with that part of the world for Americans.

wealth were leaving the country. The young country also was critically short of hard currency, a situation exacerbated by the fact that cash was flowing overseas. Furthermore Congress had no taxing authority, and massive war debts, including promised pensions for soldiers, remained unpaid. It was clear that a strong central authority was needed to regulate trade—the Confederation government could not get a tariff bill through because of jealousy among the states. On the bright side—and there was not much there—new ports were now open and American ships could go anywhere they pleased, but without, of course, the protection of the Royal Navy. The vessel Empress of China sailed to the Far East in 1784–85, opening up trade with that part of the world for Americans.

The Free Trade Issue—The Downside:

The colonies enjoyed many benefits under the British when it came to trade. Their merchant vessels had been protected by the Royal Navy, and their trade with the mother country was lucrative. Now, however, the week American Navy had to protect its own merchants. American vessels were excluded from British imperial ports outside England, which meant the loss of an important trading partner. Further, Americans know longer benefited from British mercantilism. In addition, foreign nations were reluctant to enter trade agreements with the United States in fear of retaliation by the British. High duties were charged on imports to England, which hit American traders hard. The British orders in Council of 1783 barred certain goods as well as American ships from the Caribbean trade, which hit northern states especially hard. As a result of all that, shipbuilding interest were hurt, and America had find new ways to prosper in the world of trade.

The American Economy: “Anarchy and Confusion”

The financial problems of the new United States were huge. The U.S. treasury, such as it was, was empty. The national government and many other states had huge debts, and in order to have some currency so that business might be conducted, the wartime practice of issuing paper money continued; the result was rampant inflation. American paper was practically worthless, and state paper money was worth even less, if that was possible. (In Rhode Island, legal tender paper was created, and it had so little value that people refused to accept it as payment for anything.)

With no power to tax, Congress could do little to ease the situation. Nationalists such as Alexander Hamilton and James Madison wanted Congress to have a taxing authority, but their efforts came to naught, as the states were jealous of federal power to tax, having just fought a war initiated in large part over unwanted taxation. In 1781 Robert Morris tried to set up a Bank of North America, thinking that that “the debt will bind us together.” He was given near dictatorial powers, but he resigned in frustration in 1784, having been unable to stabilize the economy.

The situation even held potential danger for the government itself, as war veterans threatened to march on Congress. Before leaving Newburgh, General George Washington had thwarted one such movement, but the seeds of discontent among the former soldiers and officers remained apparent. To make matters even more confusing, economic jealousy existed among the new states. Various tariffs were applied to goods that moved between the states, and state laws came into conflict with the treaty made with Great Britain in 1783.

During this time the national debt rose from $11 million to $28 million, which included foreign debt. Those debts were never brought under control during the Confederation period—it was not until Alexander Hamilton reformed American finances under the constitutional government that America’s economic house began to be put in order.

In January 1787 Daniel Shays led a rebellion of Massachusetts farmers who were frustrated because they were unable to pay their debts because of depressed crop prices, and mortgages were being foreclosed. They captured the arsenal in Springfield and threatened to advance on the Massachusetts Legislature. Americans from George Washington to Abigail Adams were horrified by the prospect; Washington declared it “liberty gone mad,” and the situation reminded many that mob rule was sometimes seen as a natural outgrowth of too much democracy. Thomas Jefferson was less bothered by the uprising, believing that a little violence was necessary for the good health of liberty, but it was obvious that the federal government could not respond to the needs of the people.

All these events pointed up weaknesses in the American government and showed the need to revise the Articles of Confederation. Meanwhile other reforms were emerging from the fire of rebellion, such as religious freedom—the separation of church and state. Most states abandoned tax support for churches, and Jefferson’s Statute of Religious Freedom in Virginia set an important example. In the northern states of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, the Congregational Church still got some tax money. Despite their newly found liberalism, most Americans were nevertheless intolerant of views that were strongly anti-Christian.

Slavery and the Promise of Liberty

The American Revolution did not abolish slavery, although in some states the innate contradiction between the institution and the Declaration were apparent. During the Revolution, many African Americans fought for freedom in their own way—some on the British side, some on the American. Slavery was gradually abolished, but mostly where it was economically unimportant. At this stage of its history, slavery was not seen as morally defensible; even southerners questioned the morality of slavery, and no one defended it as a “positive good.” That would come later.

Slavery was an important issue during the Revolutionary War. Governor Dinsmore of Virginia had promised freedom to all slaves who would fight against the American rebels. As a result, the British army emancipated many slaves—about twenty thousand escaped to the British, including some of Jefferson’s.

During the revolutionary period, provisions for emancipation were incorporated into most northern state constitutions. Even outsiders were struck by the contrast between American cries for freedom and its practice of slavery. Samuel Johnson asked, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of Negroes?” Some Americans were equally outraged by the practice. As Abigail Adams put it, “It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me to fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”

Meanwhile, slavery was dying elsewhere in the world. In England a slave owner could not exercise his property rights over a slave. In America, excuses were found not to use blacks to fight for independence. And yet, in the words of one historian, “For all its broken promises, the Revolution contained the roots of the black liberation movement.” For blacks had been at Lexington, had crossed the Delaware with Washington, and many had been recognized at Bunker Hill and during the surrender of the British at Saratoga. In fact, British soldiers mocked the American army because it contained so many blacks. All the same, in the South the sight of a black man with a gun evoked fear. The time for full emancipation was not yet at hand.

| Sage American History Home | Federal Age Home | 1790s Part 1 | 1790s Part 2 | Updated May 28, 2020 |