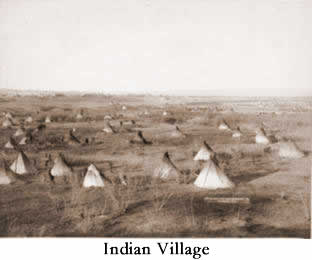

America in 1860. In 1860 the settled eastern portion of the United States reached to the region that bordered on the Mississippi River along with Texas. On the far side of the continent lay the states of California and Oregon. The vast area in between included the Great Plains, the Southwestern desert and the Rocky Mountains, soon to become the last frontier of America. Native American tribes populated the region, including the Sioux, Blackfoot, Pawnee, Apache, Navajo, Nez Perce, Cheyenne and many others. Unlike the rich, lush farmland in the eastern part of the United States, the Great Plains stretched for mile upon mile with barely a tree in sight and low annual rainfall that often left the land dry and parched. In the Rockies deposits of silver, copper, gold, lead and other minerals were waiting to be exploited. By the end of the Civil War the state of Kansas poked into the West and Nevada had been admitted in 1864, but the rest of the territory was but sparsely settled. That would soon change.

Turner’s “Frontier Thesis”: In 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner gave an address to the World Congress of Historians in Chicago with the title, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History." In that important address he put forth what has become known as the “frontier thesis.” His essential idea was that through repeated exposure to the frontier experiences, dating from the time of the arrival of the first English settlers, Americans have been exposed to conditions which encouraged the development and growth of democratic ideas. This contact with what were often primitive conditions also generated certain kinds of traits in Americans—a willingness to take risks, energy, a practical rather than theoretical turn of mind, and a sense of self-reliance and rugged individualism. Having survived these frontier experiences, Americans also developed a high degree of self-confidence and a powerful belief in their own destiny as a people and a nation.

Although critics have dissected Turner’s ideas, which he elaborated in later writings, they may easily be connected with other ideas about the nature of American society. They share much in common with works such as Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, and with emerging 19th century philosophies such as “manifest destiny.” By itself the frontier thesis cannot explain “Americanism” in any definitive way; taken together with other historical theories, however, it does make some sense. The vast extent of territory between the Atlantic and Pacific, the natural resources, the constant fighting with Indians and the isolation from most international struggles until the beginning of the 20th century all contributed to what can be defined as the American character. Like most generalizations, though, such terms must be used with caution.

Although critics have dissected Turner’s ideas, which he elaborated in later writings, they may easily be connected with other ideas about the nature of American society. They share much in common with works such as Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, and with emerging 19th century philosophies such as “manifest destiny.” By itself the frontier thesis cannot explain “Americanism” in any definitive way; taken together with other historical theories, however, it does make some sense. The vast extent of territory between the Atlantic and Pacific, the natural resources, the constant fighting with Indians and the isolation from most international struggles until the beginning of the 20th century all contributed to what can be defined as the American character. Like most generalizations, though, such terms must be used with caution.

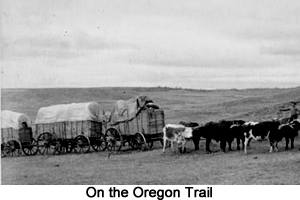

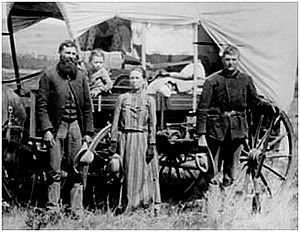

In any case, when the Civil War had ended, Americans did go west in great numbers. They went in search of gold and silver or other mineral riches, of land, space and opportunity. While some travelers came from families who had been here for generations, others were immigrants who passed quickly through teeming eastern cities and found themselves in the Rocky Mountains or the Great Plains, often gathering within close-knit ethnic communities of Germans, Swedes or Poles.

That view of the West has a certain vitality and charm—brave pioneers facing the elements with only what they could carry in a covered wagon; but it also has an ugly side: gross and careless exploitation of resources, or the driving of Indians who had lived in western areas for centuries onto reservations often hundreds of miles from their native soil. That rugged American individualism, which so many have admired, has also led from time to time to less-than-admirable behaviors: a certain degree of lawlessness, a don’t-give-a-damn self-centeredness and a healthy contempt for even legitimate authority.

For good or ill, the pioneers came, they saw and they conquered. They plowed and farmed and built and mined and hunted. They brought millions of acres of what was once thought to be desert land into cultivation. They hammered down thousands of miles of railroad track and discovered passes through the formidable mountain ranges. They constructed villages, towns and cities in areas that had been virtually uninhabited as far back as one could trace. Those settlements provided what some have called a kind of safety valve for the often squalid conditions in the eastern factories and cities. America, it has been said, had only one revolution (unless one counts the Civil War) because a necessary ingredient of revolution is discontent, and Americans who were discontented could always go somewhere else—in most cases without even thinking about leaving their country.

For good or ill, the pioneers came, they saw and they conquered. They plowed and farmed and built and mined and hunted. They brought millions of acres of what was once thought to be desert land into cultivation. They hammered down thousands of miles of railroad track and discovered passes through the formidable mountain ranges. They constructed villages, towns and cities in areas that had been virtually uninhabited as far back as one could trace. Those settlements provided what some have called a kind of safety valve for the often squalid conditions in the eastern factories and cities. America, it has been said, had only one revolution (unless one counts the Civil War) because a necessary ingredient of revolution is discontent, and Americans who were discontented could always go somewhere else—in most cases without even thinking about leaving their country.

All of those factors outlined above were a powerful force in the late 19th century. Yet they combined with another, perhaps even more powerful force, the second industrial revolution. The two phenomena—the frontier and the boom in industry—complemented and fed off one another. Industry helped build the railroads, tamed the Great Plains for farmers and ranchers and provided the tools they needed to survive in great numbers. The west provided space and resources—space for those who became weary of the drudgery of the factory and resources in the form of raw materials industrial production. Together these elements transformed the country from a rich, vibrant, but in many ways naïve and innocent country into the most powerful industrial force on the planet. The United States has more or less continuously maintained that position into the 21st century.

Cowboys and Farmers: Farming on the frontier was challenging to men and women accustomed to rich land, plentiful rainfall and close-knit communities such as existed in the Ohio, Hudson, Susquehanna, Tennessee, Cumberland and other eastern river valleys. The Plains by contrast were flat, dry, treeless and immense. The wind that blew across the prairies was often seen and felt as a ghostlike thing, a spirit that sometimes drove people mad. Water was as valuable for some as gold, and frequently fought over.

The fact of life about farming and ranching in the West was that while land was plentiful, water was scarce, and the competition for resources often degenerated into violence. The value of cattle depended upon the ability of the rancher to get his herd to market, which often meant driving them hundreds of miles over open plains to get to the nearest railhead. Abilene, Kansas, became one of the first towns developed as a center for the shipment of cattle. Its developer, Jesse Chisholm, introduced the enterprise to Abilene and sent scouts out to attract ranchers, thus giving rise to the famous Chisholm Trail.

The fact of life about farming and ranching in the West was that while land was plentiful, water was scarce, and the competition for resources often degenerated into violence. The value of cattle depended upon the ability of the rancher to get his herd to market, which often meant driving them hundreds of miles over open plains to get to the nearest railhead. Abilene, Kansas, became one of the first towns developed as a center for the shipment of cattle. Its developer, Jesse Chisholm, introduced the enterprise to Abilene and sent scouts out to attract ranchers, thus giving rise to the famous Chisholm Trail.

Farmers seeking to protect their crops against large herds of cattle soon discovered the new invention of barbed wire, which they began stringing across the plains to protect their crops and their water. Cattlemen often found themselves in conflict with farmers as their movements over range lands became more restricted. In addition, cattleman themselves began wiring off their ranges, and the competition for space led to wire cutting, rustling and other practices that often degenerated into violence. The resulting “barbed wire wars” sometimes had to be broken up by United States cavalry.

All the same, the cowboy was an institution in Western life. Thousands of them, many of Mexican or African-American descent, raised herds of cattle on the plains. Instead of being a romantic saga as often depicted in books and films, the life of a cattleman, as well as that of a farmer, was often dull and tedious. Driving a large herd to a railhead in Abilene or Dodge City, Kansas, meant spending days in the saddle. They rode along behind herds of animals that raised dust and had to be constantly controlled, sleeping under the stars and riding through rain and storms. It is little wonder that when the cowboys arrived at their destination and received their payoff they were ready for some excitement in the dance halls and saloons.

Frontier towns like Tombstone or Virginia City were not as wild and woolly nor as romantic as they are often portrayed by Hollywood. Nonetheless, events such as the famous “gunfight at OK Corral” really did happen. In the absence of reliable law enforcement agencies, frontier settlers owned and carried guns, to be sure, and women as well as men knew how to use them. But Saturday nights on the frontier were as likely to be dominated by church socials, dances, or meetings at which political issues were discussed (along with the prospects for rain) as by drunken cowboys rampaging in the streets shooting everything in sight. As soon as they were ready, these western settlements applied for territorial status and then statehood, and by 1912 the “lower 48” were all in the Union. (Hawaii and Alaska became states in 1959.)

|

Admission Politics. When important decisions regarding the state of the country are made, politics always play a part. As with most such issues, the big question regarding admission of new states was the impact new additions would have on the major national parties. Among the issues were the political makeup of territorial populations, their voting tendencies and governments; the impact of silver mining in the mountain states, which would in turn affect national currency issues; the impact of new state electoral votes at a time when the two parties were essentially stalemated; competition for railroad routes; and such additional issues as the fact that western territories had taken the lead in allowing women to vote (Wyoming was the first, in 1869.) The bottom line was that the admission of any new state would likely upset the political balance of power. Looking at the chart, one can readily see that the election of Republican President Benjamin Harrison in 1888 led to the admission of four new (Republican) states in 1889. It is worth noting that although Harrison defeated incumbent President Grover Cleveland in the Electoral College, he lost the popular vote by a narrow margin. Another example shows that in 1912 Republicans attempted to block the admission of Arizona because the territorial legislature was controlled by Democrats. | ||||

Western Railroad Building: Changing the Landscape

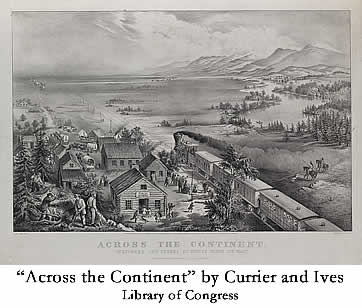

The story of the destruction of Native American cultures is intimately connected with the building of railroads across the western part of the United States. During the period of struggle between Indians and whites in the late 19th century, Indian leaders often traveled east to plead their case before sympathetic audiences. One chief was asked what could be done to help preserve the Indian cultures of the West. His answer: “Stop building the railroads.” He may as well have asked for the sun to stop shining. The building of the transcontinental railroads and all their branches was an inevitable part of the Industrial Revolution that drove America following the Civil War.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862. It laid the groundwork for the building of the first transcontinental railroad. It provided for the allocation of strips of land to be used as rights-of-way for building the railroads. Land sales could then help fund construction costs. The building of the first transcontinental railroad by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies was a monumental feat. Whether the men were battling winds and blizzards on the open plains, or tunneling through the Sierra Mountains at the painfully slow rate of eight inches per day, the work was grueling and dangerous. Every mile of track was laid by hand; every spike was driven by strong men with hammers; every wooden tie was lifted into place by railroad workers, sometimes called “Gandy dancers.” The workers who built the railroad came from the ranks of immigrants who flooded the country following the Civil War: They were primarily Italians, Irish, and Chinese.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862. It laid the groundwork for the building of the first transcontinental railroad. It provided for the allocation of strips of land to be used as rights-of-way for building the railroads. Land sales could then help fund construction costs. The building of the first transcontinental railroad by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad companies was a monumental feat. Whether the men were battling winds and blizzards on the open plains, or tunneling through the Sierra Mountains at the painfully slow rate of eight inches per day, the work was grueling and dangerous. Every mile of track was laid by hand; every spike was driven by strong men with hammers; every wooden tie was lifted into place by railroad workers, sometimes called “Gandy dancers.” The workers who built the railroad came from the ranks of immigrants who flooded the country following the Civil War: They were primarily Italians, Irish, and Chinese.

The Chinese especially became very adept at the skills necessary to tunnel through the California Sierra Mountains, using hammers, chisels and black powder to blast through the rock.

Plans for the first railroad had begun well before the Civil War. In fact, the Central Pacific started building east from Sacramento, California, in 1863. But the Civil War delayed progress until 1865. Then the Union Pacific started out from Omaha, Nebraska, and the two companies worked towards each other to cover almost 2000 miles. In addition to the physical challenges of the mountains, plains, cold and heat, the workers were constantly harassed by Indians who felt that the building of the railroads across reservation lands was a violation of their treaties. Indians also understood that the railroads would bring even more white settlers into their territory, which could hardly bode well for their existence, a condition which had already become tenuous in any case. Indeed, the completion of the first railroad in 1869 at Promontory, Utah, as well as the other transcontinental lines that followed in the ensuing decades, changed the lives of the Plains Indians forever.

In addition to labor and materials, the railroads obviously needed large amounts of capital. Since the federal and state governments saw the railroads as a boon to national and local economic prospects, they were willing to underwrite much of the cost by distributing to the railroads the one commodity which they held in abundance: land. Across the vast open spaces in the West were millions of acres of arable land. That resource, however, could not be converted into profitable farming land without some means for the farmers to get their produce to market. No one would pay a substantial price for land until the prospect existed that a railroad would be constructed to move cattle, grain and other products to urban areas.

Rather than giving funds directly to the railroads in the form of grants or loans, the government divided the land along the railroad rights-of-way into square sections, and alternate sections were given to the railroads. The remaining sections were sold directly to settlers. The government could command a much higher price for land that would be serviced by a railroad, and many settlers willingly paid a premium for the promising sites. Conversely, the lands granted to the railroads could be similarly sold to settlers in order to raise the necessary capital for the actual building. There is no question that this great land giveaway benefited the railroads, the settlers and, indirectly, the workers employed in building the long lines. But the land-grant legislation also provided for the right of federal agencies to use the railroads at discount prices once they were completed. Historians have estimated that the federal government recouped most of its investment during the period of the First World War, when thousands of troops and tons of supplies were moved by rail.

Rather than giving funds directly to the railroads in the form of grants or loans, the government divided the land along the railroad rights-of-way into square sections, and alternate sections were given to the railroads. The remaining sections were sold directly to settlers. The government could command a much higher price for land that would be serviced by a railroad, and many settlers willingly paid a premium for the promising sites. Conversely, the lands granted to the railroads could be similarly sold to settlers in order to raise the necessary capital for the actual building. There is no question that this great land giveaway benefited the railroads, the settlers and, indirectly, the workers employed in building the long lines. But the land-grant legislation also provided for the right of federal agencies to use the railroads at discount prices once they were completed. Historians have estimated that the federal government recouped most of its investment during the period of the First World War, when thousands of troops and tons of supplies were moved by rail.

Any time large amounts of money change hands, the opportunity for corruption and misuse of funds is bound to exist, and the building of the railroads proved to be no exception. The owners of the railroad companies formed a construction organization called Credit Mobilier, which was owned and controlled by the same people who owned the railroads. The railroad executives then awarded lucrative contracts to Credit Mobilier, thus lining their own pockets. In order to keep the government from getting too fussy about how this shady business was being transacted, the corporation gave hundreds of shares of stock to congressmen, senators and state legislators. The pretext for such handouts was that the donations would allow government officials to exercise oversight over the roads themselves. In the end, millions of dollars were raised, often changing hands under the table; huge profits were enjoyed, to the benefit of thousands. But in the long run, many miles of railroad track often failed to produce profits and ended up being written off as losses.

What about the farmers who quickly came to depend on railroads for their livelihood? Unfortunately they soon discovered that the railroads, which had a monopoly on the only transportation medium that served their direct needs, could exploit them outrageously. Railroads charged any rate they chose, including fees for storage of farm goods such as grain in railroad-owned silos. They even manipulated railroad rates to take advantage of people in areas on short spur lines who had only one avenue to get their produce where it needed to go. Such exploitation helped to fuel the farmers’ movement which eventually became the core of the Populist movement. It also contributed to the passage of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1877.

Like most other technological advances of that industrial era, the railroads did much good and considerable harm. They changed the lives of Americans in ways of which we are scarcely aware, such as altering our concept of time; railroad managers created the four time zones. The phenomenon of the white collar job was generated largely by railroads, who employed thousands of clerks to manage schedules, billing, and myriad other jobs that were part of the operation of any large corporation.

Even today, in the 21st century, railroads move millions of tons of materials and products far more efficiently than they can be moved by any other means. Railroads no longer occupy the romantic imagination of travelers as they once did, but they remain a vital part of the American economy.

See also section on Chinese Immigration.

Major points of Railroad Construction: Three natural resources were needed to prosper in the new territory in the West: land, water, and timber for home construction. In the West, the railroads provided wood for building, and because the railroads would make farming more profitable by transporting goods to market, it enhanced the value of the plentiful land. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave settlers 160 acres of free land, under certain conditions that encouraged settlement. In addition, The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 set the wheels of railroad expansion moving.

The Land Grant System gave millions of acres to railroad builders. Railroads enhanced the value of the land enormously, but in turn they made farmers economically dependent on rail transport. Furthermore, the sale of extra land by railroad companies raised capital to finance railroad building. The race for the connection with the Pacific Coast led in 1869 to completion of the first transcontinental line at Promontory, Utah. Railroad construction was instrumental in the further settlement of the West, which in turn aggravated conditions for the Indian tribes. When the golden spike was driven at Promontory, Utah, in 1869, poet Bret Harte composed some lines in commemoration. The poem began:

What was it the engines said,

Pilots touching head to head.

Facing on the single track,

Half a world behind each back.

The first through train carrying 500 passengers arrived in Omaha within hours of completion of the link. The event was greeted with parades, fireworks, church bells, speeches, thanksgiving services and general hoopla from coast to coast. It was generally considered to be one of the most magnificent achievements of the modern world, and made the United States the envy of other developed nations.

![]()

Impact of the Railroads on Native Americans

While the building of the transcontinental railroads brought enormous benefits to thousands of American settlers and farmers, construction across the Great Plains had a devastating effect on the Native Americans who lived west of the Mississippi. Railroads facilitated the establishment of settlements that eventually became towns and cities, encroaching upon lands that the Indians had roamed freely for centuries. The railroads also brought buffalo hunters to the West, and the stories told by Indians provide a painful analysis of the destruction of the great buffalo herds. Damage to the natural landscape during and after the building also impacted the lives of Indians. The Section on Native American history will explore these issues further.

|

Cowboys and Indians. Of all the tragedies that have befallen America, from slavery to debacles in foreign policy, none is perhaps as relentlessly sad as the plight of the Indians. In 1860 the territory west of the Mississippi contained 60% of America’s land but only 4% of the population. Some 250,000 Indians roamed the Great Plains or lived in settled communities in that area. Before the Civil War they were able to stave off some of the advance of the white man, or at least to keep certain areas to themselves; but once the Civil War ended, the great land rush began to overwhelm them.

The history of the interaction between Indians and whites began with Columbus. The story is a long, tragic tale of duplicity, greed, relentless shoving, land grabs, insensitivity, xenophobia and ultimately genocide. The Indians were not without their admirers and defenders, but even “humanitarian” plans to assist Indians often backfired by giving them what they did not want or need. The Indians could have defended themselves, and often tried to do so. Yet they were unable to unify because of their cultural diversity, and thus were divided and conquered. Europeans and Americans made many mistakes in dealing with Indians. They never fully understood the Indians, and many whites still don’t to this day.

The history of the interaction between Indians and whites began with Columbus. The story is a long, tragic tale of duplicity, greed, relentless shoving, land grabs, insensitivity, xenophobia and ultimately genocide. The Indians were not without their admirers and defenders, but even “humanitarian” plans to assist Indians often backfired by giving them what they did not want or need. The Indians could have defended themselves, and often tried to do so. Yet they were unable to unify because of their cultural diversity, and thus were divided and conquered. Europeans and Americans made many mistakes in dealing with Indians. They never fully understood the Indians, and many whites still don’t to this day.

First, whites never understood the complexity and diversity of Indian life and culture. There were hundreds of tribes in North America. They differed more from each other in many cases than did the various ethnic groups that came to America from Europe. Second, whites never fully understood the Indians’ relationship to the land. For many Indians the concept of land “ownership” was foreign or even profane. Indians felt land was there for use, not abuse (although some tribes practiced “slash and burn” agriculture.) They might fight over the use of a piece of land, but not over permanent ownership. Unlimited right of occupancy is not the same thing as sovereignty, a concept alien to Indian thinking.

The building of the transcontinental railroads and their branches was the beginning of the end for the Indians’ way of life. By 1900 they had been reduced to often pitiful relics of a once free and proud people. What happened was not unavoidable, but there was a certain inevitability about the tragedy stemming from cultural insensitivity. Misunderstanding and error existed on both sides, and although the moral claim against the white settlers and the government is strong and irrefutable, the Indians managed at times to make things worse for themselves. That is not to say in any way that the Indians were responsible for what happened—they were victims by any definition—but if they had been more clever, or perceptive, or if they had put aside inter-tribal animosities and organized themselves, they might have been able to reduce the damage. The Indians have told their own story—sadly and eloquently—but perhaps the best thing that can be said about the history of the American Indian is that it is not yet over. (See Indian Stories, Appendix.)

Indian warfare operated under different rules from those of Europe, and that created further misunderstanding and hatred. Indians were hard fighters who felt that a brave enemy was a worthy opponent, and that those who could withstand pain were the bravest of all. That aspect in Indian fighting often struck the Europeans as torture. Captured enemy warriors were “allowed” to die in painful ways in order to demonstrate their courage. Further, the wearing of enemy clothing was for Indians a sign of respect, but it was seen by American soldiers as a sign of contempt or mockery when Indians donned the uniforms of captured or slain U.S. Army troops or officers.

Capturing enemy women and children was a method Indians sometimes used to increase their own tribes, a practice they felt necessary as a result of losses from warfare or disease. Paradoxically, Indians loved children, but often kidnapped them. Captured women, including whites, were often welcomed into the tribe as brothers or sisters and were generally treated kindly.

Trying to convert Indians to agriculture was often a failure. Many Indian males considered farming women’s work, and refused to do it. (That fact also made Indians in colonial times quite useless as slaves; they were quick to escape and difficult to recover.) Those who tried farming, for example, were scorned and even attacked by others. In one case when government agents tried to teach a tribe how to plow up the ground in order to plant crops, the Indians rejected the advice. The tribe worshiped the earth, and their leaders responded, “Would I stick a knife in my mother’s breast?” The agent tried another tack by suggesting burning off the surface grass before planting. To that suggestion the Indians responded, “Would we set fire to our mother’s hair?”

Many attempts were made to convert Indians to Christianity, sometimes with apparent success. But in the end, as one historian of Indian culture has said, it is very difficult to convert Indians into anything other than Indians!

Just as Indians have been called “Americanizers” of the European settlers, so were the Indians profoundly changed by their contact with whites. The four factors introduced by whites that most influenced the Indians were:

- Disease: The arrival of the Europeans meant the arrival of diseases to which the Indians had not developed immunity. The results were devastating.

- Horses: The Spaniards introduced the horse to the Indians, and one historian has called it “a marriage made in heaven.” The horse transformed the life of the Plains Indians in much the same way that the automobile changed modern people’s lives.

- Guns: The bow and arrow in the hands of an Indian brave was a powerful weapon—an Indian hunter could drive an arrow through the thick body of a buffalo while riding rapidly across the prairie. But rifles could shoot farther and do more damage, and Indians got them whenever and wherever they could.

- Whiskey: Indians did not know how to handle whiskey, and the spread of alcoholism among Indian males is a problem that has persisted into modern times.

None of those were necessarily deliberately introduced to hurt or help Indians, except for alcohol. American “diplomacy,” however, was deliberate. It failed by treating Indian tribes as if they were sovereign, European-style nations. Chiefs were not “political” leaders in the sense that presidents and kings are political leaders. True, they often followed quasi-democratic processes in electing chiefs or sachems, but the chiefs did not have the power (nor the right, perhaps) to sign treaties that bound all the members of their tribes. Even if they wanted to, Indian chiefs who signed treaties could not enforce them, nor could they control all their members, any more than the U.S. government could keep miners and settlers off the reservations. Because they were an additional obstacle to further white migration, the Native Americans lost their lands despite their attempts to defend it, and their cultures were radically changed by the end of the 19th century. By 1867 many of the nearly a quarter of a million Indians in the western half of the U.S. were originally from the East, displaced by relentless waves of settlers. Others were native to the region, with cultures suited to their environments. By the 1880s, confrontations with still more white settlers had driven the Indians onto increasingly smaller reservations, and diseases introduced by whites had decimated the California Indians and others. By the 1890s the Indian cultures had crumbled.

Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. The Nez Perce (Indian name Nimi'ipuu) were a peaceful tribe. Although they considered themselves warriors, they did not practice scalping. They lived in northern Idaho and sometimes functioned as intermediaries between western coastal tribes and prairie Indians. They had very strong feelings of attachment to their land, which included the belief that cultivating the earth was wrong. When pressured to move, they refused to give up their territory in Idaho. An old Nez Perce chief named Joseph had a son named Chief Thunder Rolling in the Mountain. who became Young Chief Joseph. One of the most dignified Americans ever, he was a wise and gentle man. When one of his braves was murdered, Joseph pronounced a “life” sentence on the murderer; that is, he pardoned the enemy brave, who would otherwise have been killed.

An early treaty had awarded the Wallowa Valley to the government, but Young Joseph did not want to leave. He had thousands of horses, which equated to wealth, and there was no room for them on the reservation. Joseph agreed to leave the reservation, but hundreds of his horses were stolen, and in retaliation, 18 whites were killed. Joseph turned out to be a prodigious fighter who was pursued by General O. O. Howard. Joseph finally decided to lead his band to Canada, and fought his way over 1000 “mountain miles.” Joseph’s chiefs included Looking Glass, White Bird and Ta Hool Hool Shute. Although the Nez Perce fought with great skill, they were finally obliged to surrender about 30 miles from the Canadian border. Finally willing to stop fighting, Joseph made a speech that was recorded by an Army officer in General Howard’s command.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gilded Age Home | American West | Indian Stories | Indian Web Sites | Chief Red Cloud | Updated February 5, 2018 |

| The Industrial Revolution in America | Gilded Age Politics | Updated February 5, 2018 |